Photo by Shutterstock.

Rice. It’s just one of the basics, right? Whether eaten on its own, or in products like pastas or cereal, this inexpensive and healthy food is a staple for Asian and Latino communities, as well as the growing number of people looking to avoid gluten.

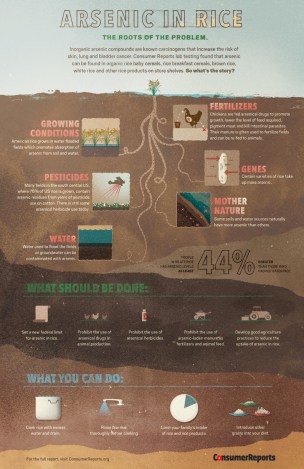

Here’s the bad news (cue Debbie Downer sound effect): The food most of us think we have more or less locked down is shockingly high in arsenic. And arsenic, especially the inorganic form often found in rice, is a known carcinogen linked to several types of cancer, and believed to interfere with fetal development.

According to new research by the Consumers Union, which took over 200 samples of both organic and conventionally grown rice and rice products, nearly all the samples contained some level of arsenic, and a great deal of them contained enough to cause alarm. While there is no federal standard for arsenic in food, according to the Consumers Union, the advocacy arm of Consumer Reports, one serving of rice may have as much inorganic arsenic as an entire day’s worth of water. (They’ve also created a useful chart of various rice products, rice brands, and their arsenic levels.)

Rice often readily absorbs arsenic from soil where chemical-heavy cotton once grew. (Photo by Shutterstock.)

How does rice compare to other grains like wheat and oats? It turns out it’s much higher because of two main factors: How and where rice is grown. The November issue of Consumer Reports, released today, breaks down both phenomena. First, the how:

Rice absorbs arsenic from soil or water much more effectively than most plants. That’s in part because it is one of the only major crops grown in water-flooded conditions, which allow arsenic to be more easily taken up by its roots and stored in the grains.

Then, the where:

In the U.S. as of 2010, about 15 percent of rice acreage was in California, 49 percent in Arkansas, and the remainder in Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas. That south-central region of the country has a long history of producing cotton, a crop that was heavily treated with arsenical pesticides for decades in part to combat the boll weevil beetle.

Not a big rice eater? Well, I’d argue this study matters for other reasons too; it illustrates what a long shadow industrial farming practices can cast over the entire food system — and the way some chemicals can cycle through our food and water, for literally generations. You see, in some areas, even rice grown organically is impacted because of what you might call the legacy of the soil.

For decades, farmers used lead-arsenate insecticides to control pests. As the name implies, these were extra dangerous because of their lead content and they were banned in the 1980s, but much of the arsenic that was left behind still remains in the soil. As Consumer Reports mentioned above, the worst offenders were cotton farms in the South, which relied heavily on these heavy-metal-containing chemicals. (Cotton farming, generally, is known to be some of the most “chemically dependent” farming on Earth.)

There are still several non-lead-based arsenical pesticides on the market, and although most are in the process of being phased out, Michael Hansen, Consumers Union senior scientist, says there is still one important pesticide, called MSMA, in use on cotton farms. Ironically, Hansen says, “they’re allowing its use because of the increasing problem of Palmer pigweed — created by the overuse of Glyphosate [Roundup] due to [Roundup Ready] GMO seeds.” (Otherwise known as superweeds.) “Palmer pigweed can lead to a 25 percent-or-more loss of revenue in cotton. So federal regulators calculated that it was worth the risk to continue using arsenic herbicides.”

Arsenic has also been commonly used in animal feed to prevent disease and make both hogs and chickens grow faster. The manure from these farms also ultimately ends up adding arsenic back in the soil (it’s even permitted on organic farms). Hansen says he’s seen ample evidence that soils that have been treated with poultry manure for years “have significantly higher levels of arsenic than untreated soil.”

On the bright side, a new law in Maryland, a huge poultry farming state, will keep arsenic feed out of chicken farms there. And one poultry drug, Pfizer’s Roxarsone, was voluntarily withdrawn from the market last spring. Meanwhile there are three others are still allowed to be used outside Maryland. “We think the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] should ban those as well,” said Hansen.

In the press release associated with the study, Consumers Union recommended that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) phase out use of all arsenical pesticides and the FDA set limits for arsenic in rice products. In response to Wednesday’s report, the FDA released an FAQ on its website describing its own testing of 1,000 different rice products. FDA officials also told the Washington Post, however, that they are “not prepared, based on preliminary data, to advise people to change their eating patterns.”

The Consumers Union, on the other hand, has a released a chart explicitly designed to help consumers limit their exposure to rice, with exact serving recommendations for both adults and children. Rice cereal, which federal surveys indicate many small children eat multiple times a day, is of special concern.

According to Hansen, rice grown in California (a relatively small subset of the U.S. industry), is also likely to have lower arsenic rates than rice grown in the South. For those interested in reducing their risk, the scientist also recommends washing the grain thoroughly before cooking it, and using a technique Hansen has observed in Asia.

“When I was in Bangladesh recently I noticed they would cook the rice with a lot of extra water — to absorb arsenic and/or pesticide residue — and then drain it off at the very end before serving it.” Hansen says this technique, over time, especially if filtered water is used, may reduce the risk of exposure to the heavy metal.