Shanghai JapaneseGoats in the Gobi Desert.

Over a decade ago, Gary Paul Nabhan moved to the plateau above the Grand Canyon to raise sheep. His timing was terrible: the beginning of one of the worst droughts on record. Some 80 percent of the pine trees around his new home, stressed by lack of water, succumbed to bark beetles. Every time he planted pastures, seedlings would push out of the earth and then wither. He was buying hay year-round, and paying dearly for it: Most of the springs that farmers relied on had gone dry, which meant that irrigation costs were up and the price of hay had doubled.

Gary Paul Nabhan in Oman, wearing desert mufti

After years of this, Nabhan gave up and moved back to lower elevation, where he better understood how to work the land. But the summer rains farmers rely on never came. It was a year without a green season.

It should be clear by now, Nabhan argued in The New York Times this week, that climate change is hurting agriculture. A rule of thumb: For every degree Celsius of temperature increase, we could see a 10 percent decrease in agricultural productivity. Bad news in an era when gains in productivity are tailing off almost as fast as the population grows.

But there’s “no sniveling or hand-wringing allowed,” Nabhan writes in his new book, Growing Food in a Hotter, Drier Land. Instead, Nabhan has traveled to the Sahara, the Gobi, Pamir, and other deserts, to learn how farmers manage not just to survive, but to thrive.

Date-palm agronomy in Nabhan’s ancestral homeland.

In the Turpan Basin of western China, for example, where it rains less than an inch a year, farmers have built tunnels, some eight miles long and 60 feet deep, that channel the flow of groundwater moving down from the mountains. They’ve developed heat-tolerant varieties of grapes, grain, and apricots. Grape trellises shade the walkways of the city. This gravity-fed system waters 50,000 acres of farmland and supports 250,000 people.

Others have noted that we’re not the first to deal with water shortages. There are all sorts of old technologies for sucking the moisture from a dry land:

Often, however, we look for technologies that let us keep farming the same way as always — just sucking harder, not smarter. Sometimes, as Tom Laskawy has noted here, that just sucks. But, if we are flexible and creative, our technologies for a hotter future won’t have to look like those used by the inhabitants of Dune.

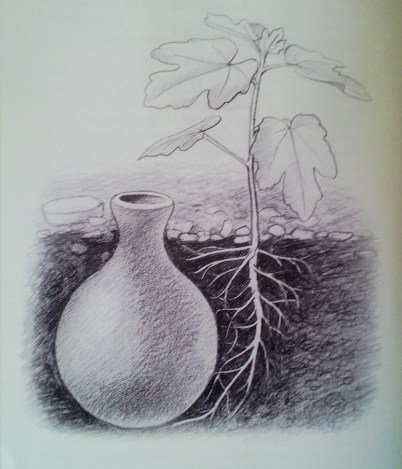

Nabhan has collected dozens of techniques, some familiar, some arcane: Waffle gardens, fog harvesting, olla pottery irrigation, catchments, fortifying soil, eliminating tillage. He has a penchant for mystics and traditional knowledge.

As we adapt to a warming world, we’ll probably also need new technology. But there’s a tendency to strive for exciting, moonshot technologies when there are simpler, proven innovations all around. Nabhan offers a nice reminder that, as we move forward, it’s sometimes useful to look back.

Growing Food in a Hotter, Drier LandPottery irrigation.