Photo by DriveBySh00ter.

Sustainability rating systems to guide consumer seafood choices are becoming as plentiful as the fish they seek to protect once were. Americans may now peruse market aisles with their choice of half a dozen pocket seafood guides: Monterey Bay Aquarium’s one week, the New England Aquarium’s another. These guides, which typically aggregate complex data into an accessible “seafood recommendation” rating, are designed to steer consumers and businesses towards sustainably harvested seafood from healthy populations. They also, we hope, give overexploited fisheries some breathing room.

But are they making a difference?

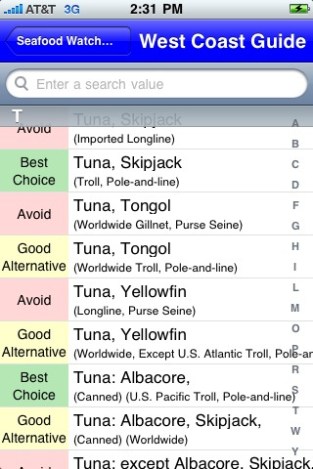

Since it began rating seafood nearly 15 years ago, the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program (one of the nation’s first and, arguably, most mimicked seafood rating systems) has handed out more than 40 million pocket seafood guides. It’s also expanded its product line to include smart phone apps, a searchable “seafood report” database, a “smart seafood buying guide,” and a “culinary chart of alternatives” for chefs. Other popular seafood-focused scorecards include ones from the Blue Ocean Institute, the New England Aquarium, and the Environmental Defense Fund.

Are these programs merely expensive ways to give consumers information they won’t use? Or are they driving measurable change — offering a truly viable way to safeguard the world’s shrinking ocean resources?

Rating the raters

One easy argument against seafood rating systems is that merely providing better information to consumers (letting them know how to “do less harm”) may not lead to behavior changes per se. Yes, these guides tell us which fish are better to buy — but they don’t offer any actual incentive to buy the better fish (other than knowing you might help stop the depletion of wild seafood.)

And that might be a big drawback. In a recent study [PDF] from the University of California-Los Angeles, researchers found that merely providing better information (in this case giving college students detailed information about their relative consumption of energy) does little to change individual behavior outright; at least not until additional incentives to conserve are offered. “Without sufficient motivation,” the authors concluded, “consumers will not incur the costs of gathering, interpreting and utilizing [such] information.”

Tom Pickerell, senior science manager at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, offered some encouraging evidence. In addition to widely distributed pocket guides, Pickerell said the program has seen over 50,000 iPhone and Android app downloads, witnessed nearly 400,000 hits to its website, and gained media coverage through more than 500 media outlets in 2012 alone.

Photo by John Herschell.

However, he added that “a very limited number of studies have [shown] anecdotal evidence on the impacts of seafood lists, and none (that we are aware of) use hard data to establish causal links between the information provided by seafood lists and consumer choices.”

Though the Aquarium may commission studies to answer this very question, it seems that the final verdict is still out. But, Pickerell added, we do know that people are motivated to buy more sustainably.

“There is ample evidence from dozens of consumer surveys,” he wrote, “which show that consumers are willing to pay more for more sustainable products and eschew products they view unfavorably.”

And he’s not wrong there. In the world of certified fisheries, where an independent third party organization, such as the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), rates and labels a particular seafood option as sustainably harvested, early reports on the market impacts of product labeling are quite good. According to MSC, consumers bought over $2.5 billion worth of certified seafood last year, often at a premium, and demand from suppliers for certification grew by 23 percent. MSC also reported that stores advertising certified fish in a pilot study saw their sales increase 200 to 500 percent.

That’s great news for sustainable certification schemes but leaves the question of seafood rating influence on consumers unanswered.

What we can say with more authority is that the influence of seafood ratings on retailers has been great. Justin Boevers, outreach manager for FishChoice.com, an organization that uses seafood ratings, like Seafood Watch, to match seafood retailers with sustainable suppliers, said, “We’re seeing demand for sustainably rated seafood increasing — retail buyers are asking for this more and more.”

I asked him if he thought consumers were driving the trend.

“That’s a tough one,” he told me. “I think businesses are doing it more because other businesses are doing it. It’s peer pressure in a way. Does consumer demand play a role? Definitely. Is it the biggest driver? I don’t know that we can say that. The big driver right now is retailers.”

That seems to be true. In 2010, the grocery giant, Whole Foods Market, committed to ridding its shelves of any wild fish labeled red or “avoid” by Seafood Watch, and in April of this year it made good on its promise. Last year Target and Walmart both made similar pledges, committing to sell “only sustainable and traceable seafood” (those certified by MSC) by 2015 and by 2013, respectively.

The good news is that American fish populations are already on an unprecedented mend. Twenty-seven depleted fish stocks have been “rebuilt” since 2000, according to a 2011 report [PDF] from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to Congress, and fully 86 percent of American fish stocks are now harvested at ecologically safe levels.

NOAA’s homegrown seafood rating system, the Fish Stock Sustainability Index (FSSI), attests to this sea change: The value of the index (which raises as fish stocks expand, are rebuilt, or are better understood through new assessments) has nearly doubled in the last 10 years.

In response to NOAA reports, The Economist declared: “For American fish, this is a good time to be alive.”

A great deal of this shift can be attributed to policy changes that set catch limits and have set out to protect specific fisheries. In other words, even if seafood ratings programs are driving real, measureable changes, they shouldn’t be the stopping point on the road to progress.