jaroslavdThese are either whimsical gems from an etsy store, or insurance for our future food security.

It is puzzling that Monsanto’s Vice President Robert Fraley recently became one of the recipients of the World Food Prize for providing GMO seeds to combat the effects of climate change, just weeks after Monsanto itself reported a $264 million loss this quarter because of a decline in interest and plummeting sales in its genetically engineered “climate-ready” seeds. And since Fraley received his award, the production of GMO corn has been formally banned by Mexico, undoubtedly seen as one of Monsanto’s major potential markets.

The World Food Prize, offered each year on World Food Day, is supposed to underscore the humanitarian importance of viable strategies to provide a sustainable and nutritious food supply to the billions of hungry and food-insecure people on this planet. Ironically, what is engaging widespread public involvement in achieving this goal is not Monsanto’s GMOs, but the great diversity of farmer-selected and heirloom seeds in many communities. Why? Because such food biodiversity may be the most prudent “bet-hedging” strategy for dealing with food insecurity and climate uncertainty.

Consumer demand in the U.S. has never been stronger for a diversity of seeds and other planting stock of heirloom and farmer-selected food crops, as well as for wild native seeds. One of the many indicators that the public wants alternatives to Monsanto is that more than 150 community-controlled seed libraries have emerged across the country during the last five years. And over the last quarter century, those who voluntarily exchange seeds of heirloom and farmer-selected varieties of vegetables, fruits, and grains have increased the diversity of their offerings fourfold, from roughly 5,000 to more than 20,000 plant selections. During the same timeframe, the number of non-GMO, non-hybrid food crop varieties offered by seed catalogs, nurseries, and websites has increased from roughly 5,000 to more than 8,500 distinctive varieties.

And yet, these grassroots efforts and consumer demand are largely being overlooked by both governments and most philanthropic foundations engaged in fighting hunger and enhancing human health. Even prior to the partial U.S. government shutdown, federal support for maintaining seed diversity for food justice, landscape resilience, and ecosystems services had begun to falter. Budget cuts have crippled USDA crop resource conservation efforts and the budgets for nine of the 29 remaining NRCS Plant Materials Centers are reportedly on the chopping block. As accomplished curators of vegetable, fruit, and grain diversity retire from federal and state institutions, they are seldom replaced, leaving several historically important collections at risk.

It is as if Washington politicians and bureaucrats were failing to recognize a simple fact that more than 68 million American households of gardeners, farmers, and ranchers clearly understand: Seed diversity is as much a “currency” necessary for ensuring food security and economic well-being as money. These households spend on average hundreds of dollars each year purchasing a variety of seeds, seedlings, and fruit trees because of their concern for the nutritive value, flavor, and the quality of food they put in their bodies. While it should be obvious that, without seeds, much of the food we eat can’t be grown, few pundits recognize a corollary to that “food rule.” Without a diversity of seeds to keep variety in our grocery stores and farmers markets, those who are most nutritionally at risk would have difficulty gaining access to a full range of vitamins, minerals, and probiotics required to keep them healthy.

However, despite what portions of the government and agribusiness don’t seem to fathom, consumer involvement in recovering access to diverse seed stocks since the economic downturn began in 2008 has been nothing short of miraculous. Some call it the “Victory Garden effect,” in that unemployed and underemployed people are spending more time tending and harvesting their own food from home orchards and community gardens than they have in previous decades. Public involvement in growing food has increased for the sixth straight year, according to the National Gardening Association. But even financially strapped gardeners are not shirking from using their limited resources to purchase quality seeds of heirloom and farmer-selected vegetables. The Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa, reports that its sales of seed packets have nearly doubled over the last five years. Another nonprofit focused on heirloom and wild-native seeds — Native Seeds/SEARCH of Tucson — saw its seed sales triple since the end of 2009. And there are between 300 and 400 other small seed companies supported by consumers in the U.S. that offer seeds by mail-order, by placing seed packets racks in nurseries and groceries, or via on the internet.

Nevertheless, the U.S. may now be approaching the largest shortfall in the availability of native and weed-free seed at any time in our history due to recent climate-related catastrophes scouring our croplands, pastures, and forests. While a few large corporations focus on a few varieties of corn, soy, and other commodity crops, there is unprecedented demand for diverse seeds to be used for a great variety of human and environmental uses in this country, and elsewhere.

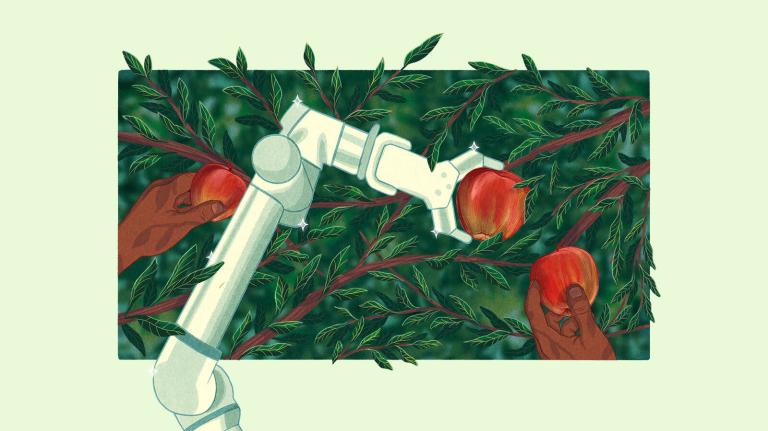

It has become painfully clear that America needs to recruit and support a whole new cohort of dedicated women and men to manage seed growouts, nurseries, and on-farm breeding and crop selection efforts for the public good. To further evaluate crop varieties for their capacity to adapt to climate change, we will certainly need many more participants in such endeavors than a charismatic Johnny Appleseed or two. They must stand ready to harvest, grow, monitor, select, and store a diversity of seeds for a diversity of needs in advance of forthcoming catastrophes. And they must value acquiring and maintaining a diversity of seedstocks, much as a wise investor relies on a diversified investment portfolio. Diverse and adapted seeds are literally the foundation of our food security infrastructure. Without them, the rest is a house of cards.

Fortunately, courageous efforts have been initiated to rebuild America’s seed “caring capacity.” The collaborative effort known as Seeds of Success, which is part of an interagency Native Plant Materials Development Program, has trained dozens of young people at the Chicago Botanic Garden to collect seeds of hundreds of native species over the last few years. In the nonprofit sector, Bill McDorman of Native Seeds/SEARCH has organized six week-long Seed Schools around the country that have trained more than 330 gardeners and farmers to be seed entrepreneurs.

Elsewhere, Daniel Bowman Simon, now a graduate student at Columbia University, has helped hundreds of low-income households (eligible for USDA Food and Nutrition Program assistance) to use their “SNAP” benefits to purchase diverse seeds and seedlings of food crops at farmers markets in order to produce not just one meal, but many. In light of recent unjustified critiques of the SNAP program during farm bill debates, it is surprising that fiscal conservatives did not acknowledge how providing financially strapped families with seedstock may be one of the most cost-effective means of reducing food insecurity over the long haul. It is tangibly giving the poor the “means to fish” rather than a single meal of a fish. With more than 8,150 farmers markets in the U.S. today, compared to 1,775 in 1994, the potential for this seed dissemination strategy to help meet the nutritional needs of the poorest of the poor has never been greater.

Regardless of whether U.S. states ever require GMO labeling or ban GMOs entirely as Mexico has done, there is abundant evidence that we need to shift public investment — from subsiding market control by just a few “silver bullet” plant varieties, whether genetically engineered or not, to supporting the rediversification of America’s farms and tables with thousands of seedstocks and fruit selections. Instead of spending a projected forty to one hundred million dollars on developing, patenting, and licensing a single GMO, perhaps we should be annually redirecting that much public support toward further replenishing the diversity found in our seed catalogs, nurseries, fields, orchards, pastures, and plates. With growing evidence of the devastating effects of climate uncertainty, now is not the time to put all of our seeds into one basket.