I have an involuntary reflex to the word “superfood”: It makes a single eyebrow twitch upward. Or, if I see the word in a story pitch, another reflex causes a spastic finger to delete the email. This reflex stems from Pavlovian conditioning: Every time I have heard the word “superfood,” I soon after find that someone is spoon-feeding me a hot bowl of hype.

So what I’m about to write here comes as a surprise even to me: Moringa should be the next superfood!

The thing is, moringa is different. If it becomes an obsession for rich, toned, hyper-vigilant Westerners, it wouldn’t be just another annoying fad. It would actually help the people who really do have to pay close attention to what they eat — because they are in danger of suffering malnourishment. It would provide money and nutrition to people in poverty. And it might just make Westerners a little healthier. And, yeah, it would also probably be an annoying fad (but I could live with that).

The American communal consciousness has a difficult time caring about poor people in other countries, but fixates intensely on the possibility of gaining superpowers by eating superfoods. It’s nice to be able to direct the power of the latter toward the former.

Moringa tree.Kuli Kuli

And the thing is, moringa really is an amazingly nutritious plant. It’s a tree that grows like a weed throughout the tropics, all around the world. The leaves are packed with vitamins, potassium, calcium (way more than milk), and iron. They provide nine times the protein as an equivalent serving of yogurt. Moringa has been used in several cultures as a form of medicine, and there is some evidence that it may have some anti–bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer effects. Fidel Castro credited his recovery from sickness, a few years back, to moringa. Basically, it’s supposed to cure everything. I won’t be going down that rabbit hole, but you’re welcome to; here’s the entrance.

All of that is really good news for the paleo-vegan Crossfit enthusiasts of Wall Street, but it’s even better news for do-gooder greens and Peace Corps types who want to be healthy and help the poor.

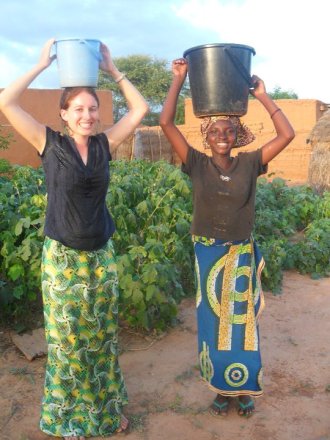

Lisa Curtis, left, in Niger.

Lisa Curtis is one of the do-gooders. She and several friends have founded the company Kuli Kuli to bring moringa to the masses. Last week, I met Curtis in Kuli Kuli’s office in Oakland. The business occupies a single modest room over a coffeehouse. Curtis, who is petite and soft-spoken, offered me some green cake — its frosting and crumb colored by powdered moringa. It was delicious, but I don’t know that I could detect the flavor of our superfood: It just tasted like cake. Moringa doesn’t have a very strong flavor, Curtis said. “It’s earthy, a little grassy,” she told me. “A lot of people say it tastes like green tea.”

We sat at a table in the center of the one-room office and Curtis told me the story of how she became a moringa booster. She was working as a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger; her village didn’t have a market, so her food choices were limited.

“I had no fresh fruit or vegetables or anything,” she said. “I was basically just eating millet, so I was actually starting to feel malnourished myself.”

She was working in the health center and the local nurses suggested that she eat moringa. After they explained what it was, she tried it and immediately felt better. Then she did a little research and thought, “Oh my God, this is arguably the most nutritious plant on the planet, and it grows really well in hot dry places where nothing else grows, like Niger, Haiti, India — places that often have high rates of malnutrition.”

It turned out that Curtis wasn’t the first Peace Corps volunteer to discover moringa. Various NGOs have studied its potential. The Philippines declared it the national vegetable in an effort to boost its popularity and improve health.

Curtis started asking around to learn why no one was growing the tree as a food crop. “Why would we grow it if there’s no one to buy it?” they asked her. It’s hard to sustain the cultivation of any crop unless there is a market for it, and it’s hard to build a market demand by convincing poor people to eat more vegetables. Moringa was seen as starvation food.

Curtis had to leave Niger early after a terrorist attack, but she wanted to keep working with the female farmers she’d met in Africa. When she got back to the U.S. she realized that she’d arrived in the largest potential market in the world for moringa. “Americans love our superfoods, we love our kale, we love our quinoa, we love our chia — can I make them love moringa? And can I make that a way to get more women in West Africa to grow it and use it? And earn a livelihood selling it?”

Four years later, Kuli Kuli still feels like a tiny startup, but it has products in some 300 stores across the country: Whole Foods, Fred Myers, and Fresh & Easy. It sells moringa bars (imagine a better tasting PowerBar with the equivalent of half a cup of leafy greens packed inside) and powdered moringa, for smoothies and cooking. It buys from a group of 500 farmers, a mostly female cooperative in northern Ghana. (Curtis wants to source from Niger — but so far logistics in that landlocked country have proved too difficult.) It has planted some 70,000 trees.

Kuli Kuli pays about 30 percent over the market rate for moringa to ensure that the farmers get a fair wage and that the company has a stable, high-quality supply. Curtis believes starting a truly triple-bottom-line business is the best way for her to make a difference.

“If I think of what I could accomplish as a Peace Corps volunteer, my scope of impact was so small and limited. And then I even think of — I’ve done a bunch of internships, I’ve worked at the United Nations for a little bit, I worked at the White House, I worked at a nonprofit — to me it seems like this is the most direct way to make an impact, because we are directly working with the people. It’s a shared fate — we are working together.”

I took home a few Kuli Kuli bars. My favorite is the Black Cherry flavor. They’re about $2.25 each if you buy them online. They fill me up in a way that feels energizing and virtuous, rather than sinful. I like to think about the fact that there’s a half-cup of leafy greens packed into each one, and I like to think that by easing my own hunger, I’m helping someone else stave off hunger. Finally, a superfood that — no matter the hype — really does make me feel great.