Rachel Signer

Here’s the best way to start a visit to New York City’s New Amsterdam Market: a small nibble of a hearty Finnish Ruis bread round, made with rye from Upstate New York and topped with a slice of locally made cheese. From there, you might sample some dishes by a chef promoting his latest cookbook; grab a loaf of “multi-ethnic” bread made by Hot Bread Kitchen, a social enterprise designed to empower its minority and low-income employees; snack on locally made grass-fed beef jerky; and wash it all down with Brooklyn-brewed kombucha.

Since 2005, every Sunday has seen the parking lot of the former Fulton Fish Market site at Lower Manhattan’s South Street Seaport transformed into a bustling agora selling artisanal foods made with locally sourced ingredients from sustainable farms — all this, beneath the roar of an interborough highway.

Those who come — a small but dedicated group, about 50,000 annually — not only love to shop locally and organically, but also appreciate the history of the site. As far back as the late 17th century, the South Street Seaport was a place for Long Island farmers to sell their produce, and over the course of 200 years it became a main port for fish and seafood. The Fulton Fish Market building, now vacant, was built by Mayor LaGuardia in the 1930s.

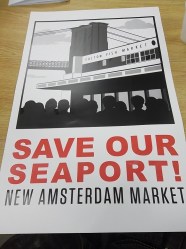

But now, the New Amsterdam Market is likely facing its last summer at the Seaport. In its place, the Howard Hughes Corporation plans to build a complex of luxury hotels, high-rises, and a concert venue. The city council, which recently voted to approve the company’s plan for the Seaport, is calling the development a victory for local food, but while the Hughes Corp has plans for some kind of “food market” that uses local and regional ingredients, the organizer of New Amsterdam will likely not be involved, and it is unclear if any of the current vendors will, either.

Perhaps it’s not news that real estate is king in New York, or that the city’s government will always go with big money and big development over small business. But what’s new here is that the city and its business partner have co-opted the language of the local food movement in promoting their development visions.

At a time when local food boosterism is growing in mayor’s offices across the country (Seattle and L.A. recently passed general local food ordinances, and Chicago is launching an urban ag program), New Amsterdam Market is a lesson that other cities can learn from. If they want to hang on to their foothold in the urban environment, small businesses in the local food world are going to have to cultivate relationships with city governments, and anticipate encroaching development, as part of their business strategy.

In New York, resistance to the HHC development plan has been robust but ultimately futile. In March, supporters of the New Amsterdam Market turned out in the hundreds (in vain, it turned out) to dissuade the city council from approving the development plan. The general feeling among these supporters is that New Amsterdam is an irreplaceable, vital resource for the local and sustainable food movement — and that the city is blind to the market’s value as an incubator for small, start-up businesses focused on supporting sustainable farming in the region.

Rachel Signer

New Amsterdam Market is a purveyors market, rather than a farmers market. “We provide an economic platform for small, responsible food businesses that do not fit within the traditional farmers market format,” says Matt Heffernan, the market’s director of operations. “We also have farmers at our market but we gear our project towards the butchers, bakers, fishmongers, and other like-minded vendors.”

Scott Bridi, 37, is the founder of Brooklyn Cured, a traditional charcuterie that works with local, sustainable, and humanely run farms. Brooklyn Cured launched its business at New Amsterdam in fall 2010, and has largely built its clientele at the market. In recent years, it has expanded to sell at four other outdoor markets, and it now has around 30 wholesale accounts.

New Amsterdam “gives the consumers more diverse and bountiful choices than Greenmarkets,” Bridi says, referring to the city-run farmers markets. “Greenmarkets are fantastic, but they exclude producers of great products who don’t own a farm. We source our meat from local farms, but we’re more concerned with crafting great food.”

Such arguments ultimately fell of deaf ears, however. In its press release announcing the approval of the Hughes Corp development, the city council stated that the developer would be required to include a market “that includes locally and regionally sourced food items.” Council member Margaret Chin hailed “the return of locally sourced, regional markets at the South Street Seaport” — failing to note that a local market already existed there.

The New Amsterdam Market was founded by Robert LaValva, a Harvard-trained architect who was a planner for the City of New York for 10 years and later worked for Slow Food International. He envisioned it eventually growing into a large, indoor food market like Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal. He had been discussing this idea with the city council for years when it seemingly turned on him in favor of the Howard Hughes Corp.

“New York is constantly tearing itself down and rebuilding itself — that’s nothing new,” LaValva said after the development plan was approved. “But the South Street Seaport was preserved precisely so that a little segment of this oldest part of the city would be left for future generations to enjoy.”

In LaValva’s eyes, the City chose real estate value over the value of community development. His supporters and vendors wanted New Amsterdam to expand, but now it will be replaced, and nobody knows by what. There is no way to know at this point how the market will work or whether LaValva or the community as a whole will be included in the planning process.

If there’s a lesson here for other cities, it’s this: Food trucks, artisanal pickle stands, rooftop farms, and street markets all do provide economic value to our cities. But unless that value is documented, and unless these businesses and community centers have vocal and well-connected champions, they’ll go the way of many other great urban ideas: paved under for the next glittering condo development.

New York, for one, has plenty of those. What it really needs is more good food, made with good ingredients by good people.