Today the U.S. Senate passed its version of the farm bill, a massive piece of legislation that sets U.S. agricultural policy until 2023. The bill is 353 days overdue, and lawmakers will still have to reconcile it with the version making its way through the House before it becomes a law. You may recall that once there was hope for major reform in the legislation: Strip away the subsidies supporting giant monocultures, and move that money to support the kind of farming that makes people, and the environment, healthier.

Today the U.S. Senate passed its version of the farm bill, a massive piece of legislation that sets U.S. agricultural policy until 2023. The bill is 353 days overdue, and lawmakers will still have to reconcile it with the version making its way through the House before it becomes a law. You may recall that once there was hope for major reform in the legislation: Strip away the subsidies supporting giant monocultures, and move that money to support the kind of farming that makes people, and the environment, healthier.

Remember that? Yeah, not going to happen.

The bill is called S. 954, Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act, which is a bit misleading. A small fraction of the bill is concerned with risk management and even less devoted to reform. The most accurate part is the 954 — which is about how much the bill would cost over a decade, in billions of dollars. A better title would be the Crop Insurance, Conservation and Food Stamps Act.

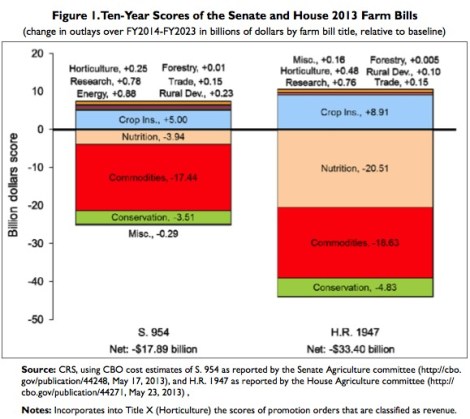

Here’s what changes actually made it into the bill: The Senate cut $41 billion in direct payments to farmers, but added a lot of that back in the form of crop insurance and disaster relief. Senators reduced the money for food stamps by $4 billion and cut conservation programs by $3.5 billion. (Details here [PDF], and Brad Plumer at Wonkblog has done a nice job breaking this down in plain English.)

You might expect the farm bill would have had an even tougher time of it: After all, coastal Democrats have constituencies pushing to cut the subsidies to big farms, and Republicans are generally against government payments. Why aren’t politicians pushing harder for genuine reform, or, barring that, just allowing the bill to die? As it turns out, the farm bill has bipartisan support, even though both Republicans and Democrats criticize it. That’s because each side gets a lot from this legislation.

Democrats get help for the poor. A huge chunk of the Senate’s farm bill, 80 percent, goes toward food stamps. (Food stamp use ballooned during the recession.) Republicans come across the aisle at the bequest of agricultural constituents. Most of the farm subsidies go to red states, or Republican districts within blue states.

There are also those conservation payments, which keep environmentalists on board, along with millions for organic farmers, money for the next generation of greenhorns just starting out, funds for farmers markets, sustainable agriculture research, and local food projects. In the end, there just aren’t many politicians who would be willing to let the farm bill die.

National Archives and Records AdministrationNear Bakersfield, Calif. Applicants for surplus food stamp grants by Farm Security Administration.

The biggest difference between the Senate and the House bills (and therefore the biggest potential fight) is the size of the cuts to food stamps. Instead of cutting $4 billion, the House has proposed cutting food programs for the poor by $20.5 billion, and some conservatives say that’s not nearly enough. (Interestingly, one of the congressmembers most forcefully for food-stamp cuts, Rep. Stephen Fincher [R-Tenn.], gets his own farm bill welfare.)

It’s true that 80 percent of $955 billion in government spending is a lot of money. But liberals like to point out that food stamps are an extremely effective form of stimulus, and note that the people who get them really need the help. As The Economist put it:

It is also hard to argue that food-stamp recipients are undeserving. About half of them are children, and another 8% are elderly. Only 14% of food-stamp households have incomes above the poverty line; 41% have incomes of half that level or less, and 18% have no income at all. The average participating family has only $101 in savings or valuables.

It’s a little sad that this is what we’ve come to: Fighting over food stamps, when once there was hope that this bill might bring about an agricultural revolution. You may have also heard of any number of interesting amendments aimed at legalizing industrial hemp, saving honeybees, labeling genetically modified foods, and limiting antibiotic use in livestock. There were hundreds of these amendments up for debate, but most never had a chance, and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid decided to cut off the debate on these stragglers and put the bill to a vote.

Of course there’s still the possibility that the House will fail to pass any farm bill at all. Or that the House and Senate won’t make a deal before Sept. 30, when the current farm bill will expire once again.