“Burrito creep” is the sort of jargon you’re unlikely to hear unless you descend deep into a highly specialized world. In this case, that world is the food company Chipotle, and “burrito creep” is the term of art employees have come up with to describe a seemingly unstoppable phenomenon: No matter what they try, the burritos keep getting bigger. And the bigger they get, the larger the proportion that ends up in the trash.

Thanks to some creative thinking at the Food+Tech Connect Hack//Dining event in New York, there may be a solution to burrito creep — one that gives eaters an incentive to control portions and cut back on the most carbon-intensive ingredients (like meat).

The point of these hackathons is to bring clever people together and set them loose on bite-sized food and sustainability problems. “The problems in the food industry are complex, and they aren’t going to be solved in a weekend,” said Danielle Gould, founder of Food+Tech Connect. “The point is to get new ideas into circulation, new people working on this, and to do rapid prototyping — to actually make a real product in a weekend.”

Alice Yen went alone to the hackathon, where she bumped into a friend from school, Marc Loeffke. Loeffke had come with a colleague, Brian Callaway, and the three recruited a teacher and software developer, Kevin Taniguchi, to form their team.

Left to right: Kevin Taniguchi, Marc Loeffke, Mariana Cotlear (from Chipotle), Brian Callaway, Alice Yen.

Chipotle had asked, “How might we use technology to enable quick-service restaurants to better measure and manage their actions to operate in a more environmentally sustainable way?”

“The challenge itself was pretty broad and vague,” Yen said. “They were just looking for cool ideas.”

But as they talked with representatives from Chipotle, they zeroed in on the problem of burrito creep. Chipotle trains workers to scoop out a precise amount of each ingredient. But as customers come through the line, people nudge the servers for more: “Can I have a little extra guac?” No one ever asks for less. Over time, the servers begin to preemptively increase the portions. The burritos creep, they grow, they expand to sizes that menace children and small dogs.

In a quick survey of people leaving a Chipotle, the team found that nearly 60 percent of the customers hadn’t finished their food.

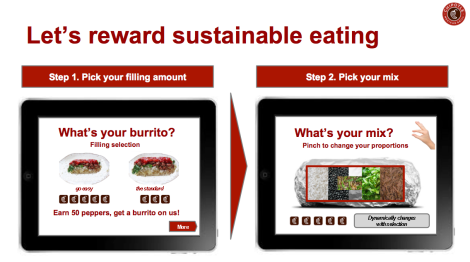

The solution is a little app that lets people adjust the amount of each ingredient for themselves. Chipotle already has a smartphone app for ordering, so the hackathon team built an addition that gives people rewards for slimming down their orders. Choose a smaller size, and you earn points that you can redeem for another burrito. The app also awards points for opting out of the more carbon-intensive ingredients — for example, you can reduce the meat portion by pinching down the meat section in a stylized cross-section of the meal.

The hackathon team also provided an option that allows people to get an even bigger burrito — say you’re an athlete, and you need the calories — but it takes an extra click to do that, so it’s harder to gorge on an impulse.

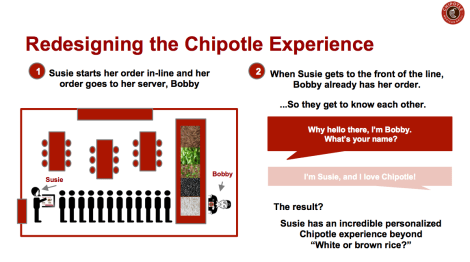

Early on, the team wanted to put the entire process on the app: You order online and then just show up and grab your food. But the Chipotle reps nixed this idea — they didn’t want to lose the interaction between customers and employees. So instead, the team tried to find a way to improve the exchange between the customer and employee. You would still order online, but then you walk along the counter as the server makes the burrito.

The team did a back-of-the-envelope calculation and estimated their app could save Chipotle over $100 million a year and save 115,000 tons of carbon — though Yen admits that the Chipotle representatives politely suggested that these calculations might be significantly off.

Maybe some permutation of this idea goes on to revolutionize the fast food industry, or maybe this is as far as it will ever get. Regardless, it’s cool to see such a good idea emerge in a single weekend.

Americans generally don’t feel like they are getting a great deal unless they are served enough food to turn themselves into human foie gras. The most powerful insight from this project, in my opinion, is that it’s possible — and even profitable — to tip the incentives back in the other direction, so that people feel they’re getting a better deal when they pick a smaller size.