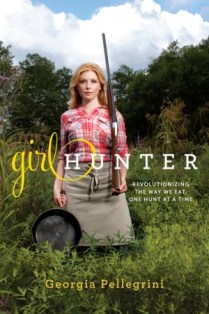

Georgia Pellegrini did not write a book about hunting to prove she was tough, or to bridge the divide between foodie culture and rural America. Instead, the author of Girl Hunter: Revolutionizing the Way We Eat, One Hunt at a Time wanted to know what it would take to spend a year eating only the meat she’d killed herself. She succeeded, and not just to woo Mark Zuckerberg, either. Girl Hunter tells a lively story of her time hunting and cooking wild boar in West Texas, turkeys in Arkansas, and ducks in the British countryside, just to name a few. And despite the mainstream Cooking Channel feel this book has on the surface (watch this trailer if you want to know what I mean), Pellegrini clearly has a genuine interest in seeing a larger structural shift to our food system. In the book, she writes:

Georgia Pellegrini did not write a book about hunting to prove she was tough, or to bridge the divide between foodie culture and rural America. Instead, the author of Girl Hunter: Revolutionizing the Way We Eat, One Hunt at a Time wanted to know what it would take to spend a year eating only the meat she’d killed herself. She succeeded, and not just to woo Mark Zuckerberg, either. Girl Hunter tells a lively story of her time hunting and cooking wild boar in West Texas, turkeys in Arkansas, and ducks in the British countryside, just to name a few. And despite the mainstream Cooking Channel feel this book has on the surface (watch this trailer if you want to know what I mean), Pellegrini clearly has a genuine interest in seeing a larger structural shift to our food system. In the book, she writes:

People tell me, “I don’t think I could do it.” The good news is that you don’t have to. But if you want to feel what it is to be human again, you should hunt, even if just once. Because that understanding, I believe, will propel a shift in how we view and interact with this world we eat in. And the kind of food we demand, as omnivores, will never be the same.

We spoke with Pellegrini recently about the book, the role hunting can play in rural food systems, and the gender dynamic she experienced out in the field.

Q. What made you want to tell these stories about hunting?

A. I am a chef, so I look at it all through the lens of food. I grew up living off the land, with honeybees and chickens, and I fished and foraged a lot. But I didn’t hunt until after I became a chef. While I worked at Dan Barber’s restaurant, Blue Hill at Stone Barns [located at the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture], we were really hands-on with the ingredients — we did everything from collecting eggs, to working in the greenhouse, to killing turkeys.

Killing the turkey was sort of my watershed moment; it sort of woke up a dormant part of me. So many horrible things happen in our industrial food system and I wanted to explore what it meant to step outside the traditional way of procuring meat, and really go back to the way we used to do it. I wanted the experience of participating in every single part of the process — from the field to the plate — and to make sure that there was no suffering, that every part of the animal was used and used with integrity. I wanted to pay the full karmic price for the meal. Your perspective as a chef changes so much when you’ve had to work hard for every ingredient. I think the food tastes a lot better that way.

Q. Can you say more about what you mean by “pay the full karmic price” of the meal?

A. There were times before when I’d go to the meat aisle in the grocery store and pick up a boneless, skinless chicken breast wrapped in plastic and Styrofoam, and not really think much of it.

[Since I started hunting], I decided that if I was going to be a meat eater, I really wanted to internalize what it means to be an omnivore. And I really do, it’s emotional, spiritual, intense. And I’ve become a more conscious eater, a more awake human being.

Photo via georgiapellegrini.com.

Q. Do you think that’s the case for most people who hunt?

A. I do. The truth is that there’s something about spending countless hours out in the woods, contemplating the rhythms of it all, that’s very calming. And for me, what I’ve seen is that all of the hunters want to bring their food home and feed their family. And they really respect it; they use all of it.

While I was writing the book, I’ve also been able to teach the folks I went hunting with how to prepare the meat they catch so that it tastes delicious. Wild game is not as fatty as most meat because wild animals are essentially athletes. So it’s harder to cook. But there’s such a great range of flavor out there that we don’t experience otherwise; we’re used to all beef and chicken tasting exactly the same because all the animals have the exact same diet and live in the exact same conditions. But wild game tastes very different depending on what it eats, and where it lives.

Q. What kinds of tricks of the trade have you shared with these hunters?

A. For one, it’s really important to age meat. It tastes so much better when it’s aged. It allows the collagen and muscle tissue to break down, which makes it more tender. I have a chart in the book that shows people which animals are good aged and for how long.

Brining is also important because it helps dry cuts of meat retain moisture, while marinating is more about tenderizing.

Q. In Girl Hunter, you talk about the fact that in certain parts of rural America, hunting is one of the best — if not the only — ways to access meat that isn’t industrially produced. Do you want to say more about that?

A. A lot of people who hunt do it as a way to feed their family [because] the alternative is Walmart, which is 15 miles away.

One of the most inspiring aspects of working on this book was seeing places in this country that are sort of forgotten, but have so much soul and such fantastic food cultures, because they don’t get to go out to eat, so the only way to share a meal is to invite people from the community over and cook for each other. So a lot these people have become really wonderful home cooks.

Q. Were you ever afraid of any of the larger animals you were hunting?

A. I think the most dangerous scenario was when I was hunting a wild boar with only a knife. It was a 300-pound angry boar with very sharp tusks, and I was with a group, so it was a lot of commotion and chaos. But at the same time it was a really interesting experience to have because that’s how we used to get our food. When we all lived in the woods, all you had was a sharp object, and it was a risk.

But generally no, I haven’t been afraid of the animals. I think you should be more cautious about the people you’re hunting with than the animals. When you’re out there, you also want make sure you’re with someone you trust.

Q. What was it like to hunt as a woman, with men who were generally more experienced?

A. It was really mixed. I really don’t fit the typical profile of a hunter, but they were definitely pretty cool to me when I got out there. When men see a woman participating in what they have done for many hundreds of years, they get quiet. They’re sort of thrilled by it. I think it’s intriguing to them that I would share such an interest. There have been a few moments when certain men get agitated or annoyed that their paradigm is being invaded by a woman. But that’s not ever the focus of the outdoors. When we’re out in nature we’re all just humans. Something wakes up in you and the whole gender thing sort of disappears.