In this series trying to figure out how we humans can best feed ourselves, I’ve been talking to lots of researchers about farmers, especially the small family farmers in Africa and Asia. If these farmers can find a way to thrive and to educate their children, it will go a long way toward simultaneously halting population growth and providing enough food to the people who need it most.

But I’ve been talking a lot about these farmers, not with them. It’s all very well to ponder the best ways to reduce poverty in the abstract, but there are people for whom these issues are as real as the dirt they plow and the grain they cook. The policies of richer countries and charities could change the lives of their family members for generations. What do they want?

Oxfam America recently brought some Ethiopian farmers to the United States, and I jumped at the opportunity to interview two of them.

Birtukan Dagnachew TegegnOxfam America

Birtukan Dagnachew Tegegn is from the village of Mechare in the north of Ethiopia. Married at 14, she had four children before her husband passed away. In that area there’s no road, and it’s a four-hour walk to the nearest town. No one owns mechanized farm equipment — so it takes a lot of physical labor to make a living. When Birtukan’s husband died, everyone assumed that she’d sell the land and move to a city. Instead, she managed to make the farm productive and profitable enough to educate her children. Her oldest son is now a university graduate with a civil engineering degree. She grows mostly sorghum and teff on her land, but she also has a plot of vegetables, and she has planted a mountainside with various trees.

The other farmer I talked to, Dadi Buta Bedada, works 12 acres in Karsa Ilala, in the middle of the country. He’s close to a newly renovated farmer’s training center. After getting training, the amount of food he was able to produce skyrocketed. He grows potatoes, pepper, shallots, corn, wheat, sorghum, barley, and teff. “I was getting about .8 to 1 ton per acre,” he said. “But now I get 5.5 to 6 tons per acre.”

My line of inquiry was simple: I wanted to know what Birtukan and Dadi Buta hoped to achieve with their farms, and what they needed to make those dreams a reality. What they want, of course, is what everyone wants: To give their children a secure, prosperous life. “We did not inherit anything from our parents, and what I want to do for my children is to leave behind something useful, so that our children and grandchildren will have something to build on,” Dadi Buta said.

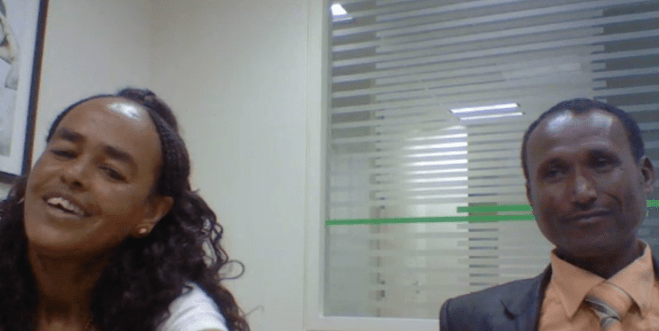

For 45 minutes I stopped thinking about what economics and development theory suggested would work; instead, I just listened to these two farmers. We spoke on Skype, through a translator.

Birtukan and Dadi Buta on Skype at Oxfam America in Washington, D.C.

Birtukan and Dadi Buta both told me they needed labor-saving technology. That huge increase in yields that Dadi Buta achieved came at a price: a lot more work. Instead of just tossing handfuls of seed onto the ground, he’s carefully planting in rows. He works a compost pile and applies fertilizer to the land.

“It’s even worse for women farmers,” Birtukan said. “Planting barley or corn in rows takes a lot of labor and it’s even more difficult for women than men. I don’t have a row planter — they weren’t introduced here because it’s so remote. We don’t even have herbicides, and it takes a lot of labor to remove weeds. Row planters, threshers, herbicides, insecticides, and even fertilizers are not really available because of transportation problems.”

This surprised me because I’d written a previous piece arguing that increasing the amount of labor needed on a farm was a good thing: If the main point of agricultural development is to reduce poverty, then you want the farms to provide as many jobs as possible.

So why didn’t Birtukan and Dadi Buta just put their children to work? “Children are now going to school, so we may get half an hour of their time a day,” Dadi Buta said. And there are good jobs available for someone with an education. Ethiopia is farther along than I’d expected: Alternative jobs are out there, the farmers said; not everyone needs to stay on the farm anymore.

“I would be very happy if my children were farmers, but educated farmers with university degrees,” Birtukan said. “The problem is that there isn’t enough land. Farming is the best occupation, and we are feeding the world, so I have respect for agriculture. But I have only 4.5 acres of land. This land is not sufficient to support my children if they are educated.”

Look at the U.S., she said. Farmers in the U.S. aren’t poor — they are respectable, they are educated. But in order to support that level of upper-middle-class income, each farmer needs a lot of land.

We didn’t get into this nuance during the interview, but my vision of the agrarian ideal has farms staying relatively small, but earning money in ways beyond growing food. In my utopia, farmers would be paid for land stewardship, for sheltering biodiversity, for water purification and carbon capture. But the question is, who pays for all that, and by what mechanism? The state would be hard pressed to provide the money. The Ethiopian government is investing a huge amount — 14 percent of its national budget over the last decade — on agriculture for things like farmer training, yet it still relies on help from groups like Oxfam to make progress.

Both Birtukan and Dadi Buta have plans to produce more food and provide more jobs. Dadi Buta is a beekeeper, and he’d like to expand to have a real honey business. Birtukan has plans to build a chicken hatchery and employ other women farmers. Her second son is a truck driver, and she’d like to buy him a truck so that he’d be able to work for himself. But all these things take money, and it’s hard to get loans. Plus, Birtukan doesn’t have the land to build a hatchery.

Obviously, these two farmers don’t represent all rural Ethiopians, let alone all small farmers around the world. But their perspective does provide a snapshot of how agricultural development works. Invest enough money in farmer training and people start producing more food, which allows them to send their children to school, which allows them to become the doctors and engineers and middle-class farmers who can help steer a country to stability and affluence. Instead of a single mother moving her children to an urban slum, Birtukan became a single mother sending her children to university. For Dadi Buta and Birtukan it’s very simple: Increasing yields is the way to prosperity — they just want the tools and education that will allow them to produce more food.