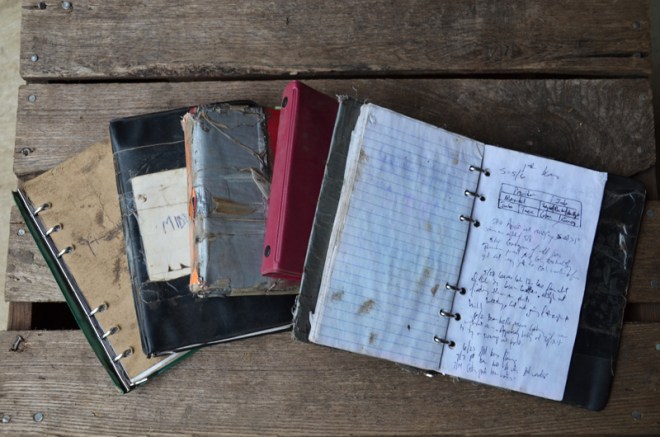

It’s a Sunday ritual for Henry Brockman to drive down to the fields and walk the rows, taking notes about the growing season in one of four notebooks he keeps in his truck. Work boots pressing into the soil, braced for Central Illinois’ moody weather, he walks because the paces help him think, sliding his pen over to the book’s margin to scrawl a thought or a line of poetry.

They’re “little encapsulations of a time and place,” He says. “A farmer’s life is about knowing what time it is.”

Dozens of such notebooks fill boxes at his home, which anchors Henry’s Farm, a 12-acre Eden located in the fertile bottomland of the Mackinaw River Valley outside of Congerville, Ill. And Henry is not the only one of six Brockman siblings who has picked up the pen. Most of the family not only farms, but also writes — a trait, Henry’s sister Terra says, that is “genetic.”

The Brockmans matter in the shifting world of farming because they are taking the time to catalog their work, their days, their thoughts. Well-educated and multi-cultural, they write about the challenges of the seasons, the hard realities of farming organically, and the turmoil of climate change. If you’re pondering the ag life, or if you just want to understand in a deep way where your food comes from, their works are a must-read. Ecologist Sandra Steingraber likens Terra’s writing to that of Wendell Berry. The work, she says, is “like a modern-day Farmer’s Almanac.”

Here, have a taste, from Terra’s James Beard Award-nominated book, The Seasons on Henry’s Farm:

Last week I sliced my finger while cutting the turnip greens during the harvesting marathon, but didn’t realize it until I returned home hours later because my fingers had been numb and almost bloodless. If you put yourself into the muddy boots and frozen feet of a person who has been doing hard manual labor out in the fields every minute of daylight for the past eight months — through the brutal heat of summer, through downpours, through freezing rain and wind, hour after hour, day after day, month after month — then you can imagine how pleasant winter begins to look.

Jotting down their thoughts was originally a way to bring CSA and farmers market customers the backstory belonging to the food on their plates. Terra, who has a degree in English literature, initially wrote a two-page newsletter she calls “Food and Farm Notes” that she would hang from the rafters of their stand. Filled with facts, literary references, and tidbits and about the produce available at market that day, it garnered a cult following. Copies would disappear within an hour. She began sending it by email, and that eventually led to her book.

In 2006, Henry authored Organic Matters, a book now included in curricula at Illinois Wesleyan University and at Arizona’s Prescott College. Another sister, Teresa, who farms fruit and aronia berries at her Sunny Lane Farm, blogs about the rural life and Henry’s wife, Hiroko, is an artist who illustrates all of their work. You can read some of their work, and buy their books and chapbooks, here. They also post work and updates on Facebook.

The next generation has inherited the writing gene as well. Henry’s 21-year-old daughter, Aozora (Zoe), wrote poetry and essays about growing up on the farm in a chapbook, The Happiness of Dirt, and is now studying creative writing at Northwestern University.

But like many young people raised on farms, Zoe is unsure whether she’ll dedicate her own life to agriculture. “I love having grown up on a farm, and didn’t know how different and wonderful it is until I went away,” she says, but adds: “It’s becoming harder and harder to be a farmer.”

“Climate change is very hard on us — each year is different and very chaotic,” Zoe continues. “This year we had rain, but the past years it was super dry. Dad had to irrigate and we’d wake up every three hours and place drip tape on different rows.”

Here’s a bit from her essay “Kill or be Killed”:

No rain for weeks made cracks appear that sliced the soil into great slabs, heavy as rock, and those I moved — teeth grinding slow to keep from thinking of the rays of sun that lit my back ablaze and how my fingertips felt ripped open each time I dug at the coarse soil, in search of smoothness.

While Zoe contemplates what to do with her life, she and her father have decided to write another book, cataloging the two different generations contemplating their farming life.

Next for Terra, 55, who founded and heads the Land Connection, a nonprofit linking available farmland with new farmers, is a “very approachable” book on soil. “Soil is precious and complex, like a giant internet,” she says. “Civilizations have risen from the soil and they’ve fallen due to agriculture.”

Come January, Henry is taking a year off from farming to live in rural Japan with Hiroko. There, he says, he will begin sifting through the notes taken in the fields over the past 22 years. The rest of the family will keep Henry’s Farm in operation while he’s away.

Although he will harvest up to Thanksgiving, an annual ritual will take on a bittersweet twist this Saturday when hundreds of customers, friends, and readers who’ve yet to meet the family descend on Henry’s Farm for a farm tour, bonfire, and dinner at long tables set among rows of vegetables.

Upon hearing the news, one regular farmers market customer announced on Facebook: “My farmer is taking a Sabbatical!” “If every 21st century American had a relationship with a farmer, much as we have a preferred auto mechanic, we would all be heedful of what we eat and the labor that it requires to produce it,” she wrote. “Maybe we would eat less, enjoy it more and be the better for it.”