This story was published in partnership with the Center for Public Integrity and The World.

Everywhere Randy Souder looked, he saw mud. On his soggy fields. In the mechanized crannies of his planter. Along the rural road to his house, where he’d left a trail of clumps. It was late June, and record-breaking rain had pushed Iowa’s corn-planting rate to its lowest level in nearly four decades. Souder hoped the summer sun would dry the soil quickly.

Once it did, Souder could finally start the critical next step: Bring in a rig with tires tall enough to clear shoulder-high corn stalks and cast a 100-foot swath of fertilizer over his crop. That blast of nitrogen — the farming equivalent of pixie dust — would make the ears grow large and dense with kernels if applied at the right time.

“When I started 40 years ago, my fertilizer pounds per acre [were] less than half of what they are now,” Souder said. “I started out with a 110-bushel yield, and I’m thinking, ‘It’ll never get any better than this.’ Now we’re pushing 300-bushel on the corn.”

Corn and soybean farmer Randy Souder poses with his planter near his home and farmland near Rockwell City, Iowa. Joe Wertz / Center for Public Integrity

But this agricultural alchemy comes with a toll. In America’s Corn Belt and around the world, some of the fertilizer applied to fields escapes the soil in new forms that contaminate and warm the planet.

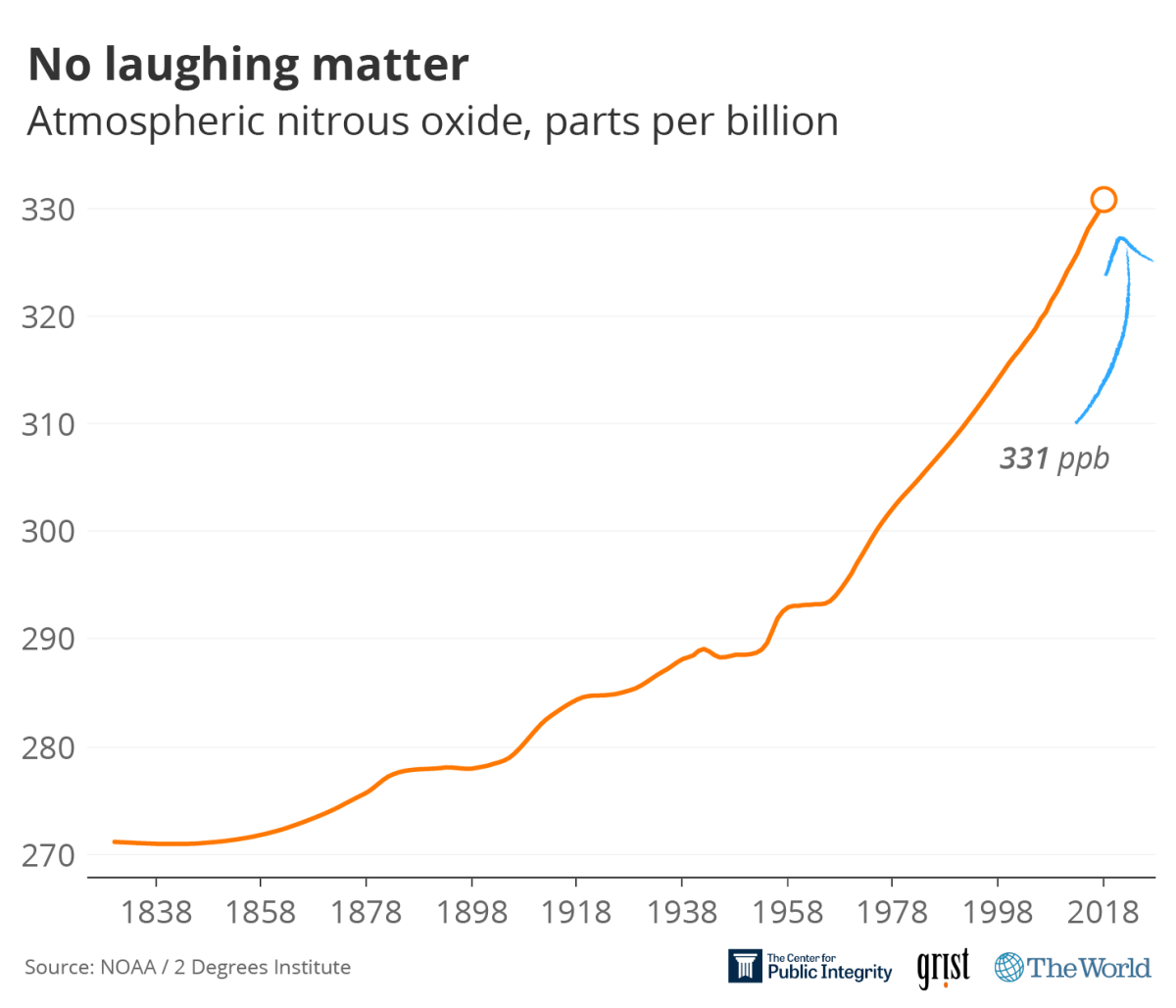

Some of these compounds enter the atmosphere as a potent greenhouse gas that’s now at its highest concentration in the last 800,000 years, helping fuel climate problems like the flooding that upended farmers’ lives last spring.

Other fertilizer byproducts contaminate water wells, especially in agricultural areas, where the U.S. Geological Survey says one in five has levels exceeding federal health limits. These contaminants also wash into streams, rivers, and lakes, where they become what the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency calls “one of America’s most widespread, costly and challenging environmental problems.”

This pollution stream feeds the kind of algae bloom that was so toxic in Lake Erie in 2014 that officials in Toledo, Ohio, warned roughly 500,000 customers not to drink or come in contact with the city’s tap water for three days. The nutrients flow more than a thousand miles from agricultural states to the Gulf of Mexico, where they nourish an aquatic dead zone that in summer 2017 grew as large as New Jersey.

Deep cuts to nitrogen runoff and emissions are critical, researchers say, both to curb mounting hazards from water pollution and to stave off the most cataclysmic consequences of rising global temperatures.

And while it’s a smaller environmental danger than carbon, scientists say fertilizer is an underrated and growing threat — one that’s more complicated to solve.

“We’re not producing CO2 on purpose,” said James Galloway, an environmental scientist with the University of Virginia. “You need to have that nitrogen to grow the food, and the more people there are and the higher they’re eating up the food chain, the more nitrogen you need.”

The rate that farmers in the U.S. are using nitrogen fertilizer is more than 40 times higher than it was three-quarters of a century ago, far outstripping population growth. Trouble was anticipated decades ago. But in the U.S., legislators and regulators alike have avoided confronting the problem directly.

The EPA’s science advisors have recommended nitrogen control since the early years of the agency’s existence, to little avail. Agriculture, in fact, has evaded much of the federal environmental oversight that falls on other polluting sectors. The $133 billion industry is largely the regulatory responsibility of state authorities, who favor recommendations and voluntary cooperation instead of rules and enforced compliance.

Farmers, agribusinesses, and groups representing their interests say education and collaboration at the state level is the best way to manage a highly varied and vital industry that struggles with sometimes-crippling financial challenges. Critics, including researchers, local officials, and activists, say this arrangement means fertilizer use has escaped environmental, health, and safety scrutiny applied to other chemical compounds.

An investigation by the Center for Public Integrity, Grist, and The World found that when states do try to regulate farms and reduce pollution linked to fertilizer, rules are often derailed or softened after industry pushback and political pressure.

[protected-iframe id=”88cd68615c481f0e7b626db4c4e97670-5104299-118507429″ info=”https://www.pri.org/node/184408/embedded” width=”100%” height=”70″ frameborder=”0″]

Listen to the radio version of this piece from The World.In Ohio, for instance, an agency commission in 2018 bowed to industry demands and scuttled an effort to set controls designed to reduce runoff feeding recurring algae blooms in Lake Erie. In Wisconsin, another state struggling with nitrate contamination, the governor’s ongoing effort to enact manure and fertilizer restrictions has been slowed by Republican legislators and vocal resistance from farm groups.

“Governments are pretty captured by the industries,” said Timothy Wise, an author and a senior research fellow at the Global Development and Environment Institute at Tufts University. “And farmers are getting more dependent on these [fertilizer] inputs.”

‘The grand challenge’

After months of winter snow and spring rain, the Mississippi River swelled over its banks near Davenport, Iowa. Once the temporary levee was breached in late April, record floodwaters consumed two city blocks in six minutes.

“All of a sudden it was like a war zone,” said Dan Bush, who owns three downtown bars that employ about 50 people. As the water invaded, swamping alleys and parked cars, Bush said the sky filled with helicopters, drones, and birds scouring for a dry spot on which to perch.

The Raccoon River overflows its banks in Des Moines, Iowa, in March 2019. Phil Roeder / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

The floodwater stopped half a block from Bush’s bars. But he and other business owners spared direct flood damage suffered a drought of customers due to closed streets, downtown construction, and rebuilding.

“Now we’re seeing people just not renewing their leases or moving out early because they just can’t float it,” he said.

The flooding near Davenport occurred during the wettest 12 months in Iowa’s history. The spring floods killed three people throughout the Midwest. The toll in Iowa, from thousands of damaged homes to punishing economic losses for farms and other businesses, could top $1.6 billion.

Some parts of the state with the heaviest rain and worst flooding had not long before suffered from drought, a feast-and-famine swing that researchers call a hallmark of climate change.

A growing number of scientists say better management of agricultural lands is key to making necessary deep cuts to non-CO2 gases that are helping warm the planet. The National Academy of Engineering in 2008 identified nitrogen management as one of the “grand challenges” facing the world.

Nitrogen is a building block for biological life on earth. It’s the most abundant element in the atmosphere, but most plants can’t make much use of it unless it’s combined with carbon, hydrogen, or oxygen. Nature, largely through lightning and bacteria, provides only so much of that “reactive” nitrogen. Fertilizer is the workaround.

“People make four to five times more reactive nitrogen than natural, terrestrial processes,” said Galloway, the University of Virginia scientist. “And on a global scale, it’s just showed no signs of stopping.”

A dramatic expansion of fertilizer use in the last century has helped drive an increase in cropland emissions that are the single-largest source of manmade nitrous oxide around the world. Global nitrous oxide levels increased 55 percent from pre-industrial to modern times.

New research suggests those emissions accelerated beginning in 2009, possibly due to the compounding effects of too much nitrogen, and likely at a rate much faster than predicted by models used by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Though its levels are still far below those of two other climate-warming agents, CO2 and methane, scientists say nitrous oxide is especially hazardous. It’s a common greenhouse gas with a long atmospheric lifespan — more than 100 years — that also depletes the ozone layer.

But fertilizer use on farms has escaped most federal environmental regulations that apply to other polluting industries. Cornerstone environmental laws such as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act were written at a time when the top concern was managing pollution from industries with smokestacks and tailpipes, not soybeans and tails.

Nearly a half-century ago, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization recognized that intensive fertilizer use posed an environmental and public health hazard. Around the same time, U.S. environmental authorities acknowledged that agriculture was a major source of reactive nitrogen pollution that needed to be regulated.

“All known trends appear to be ones that can be managed and kept within control, if appropriate steps are taken now,” the EPA’s Science Advisory Board wrote in 1973.

But few steps were taken — then or in the decades that followed. That’s despite the fact that the EPA board kept offering information and advice, from a framework the agency could use for regulations to findings that agriculture was releasing nearly twice as much reactive nitrogen pollution as fossil fuel and other industrial sources combined.

Fertilizer also contributes to other forms of air pollution, both directly and indirectly.

Most nitrogen fertilizer is produced using natural gas as a chemical feedstock and fuel source. Natural gas is primarily methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. U.S. nitrogen fertilizer manufacturers reported releasing 220 tons of it in 2016, the most recent data available, but research led by scientists at Cornell University found those emissions could be far worse. Using a car outfitted with sensors, researchers analyzed air samples near the country’s largest fertilizer plants and estimated methane emissions were 140 times higher than levels reported to the EPA.

Nitrogen fertilizers also drive releases of ammonia, a key ingredient of smog and fine particles. Fertilizer manufacturing was responsible for one-third of reported releases of ammonia from 2012 to 2017, according to EPA figures.

Use of fertilizer contributes to increased ammonia releases from farms and livestock operations, researchers say. A 2019 study published in Nature linked fertilizer to 4,300 premature deaths from particulate pollution annually, mostly in Corn Belt states and regions nearby.

“The impact of agriculture on air quality and climate change is not in the forefront of the public eye as fossil fuels are, even though agriculture is a major contributor to both,” said University of Minnesota scientist Jason Hill, the paper’s lead author. “Even if we solve the fossil fuel problem over the next 50 years or more, we still have to eat.”

Farm industry representatives attacked the study, its methodology, and its funding, some of which came from the EPA, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and U.S. Department of Energy.

Some large animal operations need federal environmental permits, but farming isn’t subject to the same EPA monitoring, testing, and corrective enforcement applied to factories and other industrial sites.

The agriculture industry has worked hard to keep things this way.

Groups of individual farmers and ranchers who advise the EPA on agricultural issues consistently push for voluntary measures, bemoan the “tone” of agency communications that suggest farming can harm the environment, and say the EPA should have no role in regulating soil on farms and ranches.

The American Farm Bureau Federation declined to comment for this story. But it opposes any laws or regulations requiring the reporting of greenhouse gas emissions by agricultural operations. The federation — the largest organization representing U.S. crop and livestock producers — also opposes any EPA regulations on greenhouse gases as well as the adoption of climate change legislation that increases costs on farm businesses, which they say have little ability to raise their prices. Farms also face pressures from extreme weather, tariffs, and rising rates of debt and suicide.

Environmental policies for agriculture should go no further than voluntary measures, the Farm Bureau argues. The only role it sees for increased involvement of the federal government: giving more money to farmers for climate-adaptive technologies.

“For farmers and ranchers, regulations don’t just impact their livelihood,” Farm Bureau President Zippy Duvall testified at a 2018 Senate hearing. “Unlike nearly any other economic enterprise, a farm is not simply a business; it’s often a family’s home.”

Farming, though, is increasingly concentrated. The median acreage of cropland on farms doubled from the 1980s to the 2000s. Fewer people are operating these larger farms, which remain mostly family-owned but are increasingly specialized, mechanized, and growing products that aren’t food.

Two-thirds of the nation’s top crop, corn, goes to refineries and processors for use in ethanol biofuels and animal feed. An increasing amount of meat comes from farms that raise animals on feedlots. The largest of these operations funnel manure into pits and lagoons that can hold tens of millions of gallons and produce as much nutrient-rich waste as large U.S. cities.

A young corn crop emerges last summer from a field in Fort Dodge, Iowa. Joe Wertz / Center for Public Integrity

Environmental groups argue that farming is much more industrial than it once was and should be regulated as such.

But agricultural pushback to federal pollution rules has been so successful that there’s less federal oversight now than a decade ago.

Congress exempted large animal farms from greenhouse gas reporting requirements in a rider added to the spending bill signed by President Donald Trump in 2018. The EPA under George W. Bush and Barack Obama pushed for similar exemptions. Trump’s EPA has eased other environmental regulations on agriculture, such as repealing an Obama-era water pollution rule that farm groups opposed, which environmentalists worry could hurt future efforts to curb agricultural runoff.

But attempts to save agricultural interests money by rolling back or not proposing rules have consequences, some quite costly. Last year’s Midwestern floods are just one example.

The economy in Davenport, Iowa’s third-largest city, was drained by the mid-’80s farm crisis but had rebounded in recent years alongside $500 million in downtown reinvestment. Now the city, which draws much of its cultural identity from its proximity to the Mississippi River, is considering a project it long resisted: a permanent flood wall, a $175 million project that’s nearly the size of the city’s annual budget.

Dan Bush said he’s eager to open new bars and restaurants. But he’s worried that the flooding in April is just a taste of what climate change will bring. No place near the city strikes him as safe from flooding anymore.

“I think this is going to become the norm,” he said.

Rare rules

Jeff Broberg stood in front of his southeastern Minnesota farmhouse, leaning against a pickup truck filled with binders, research papers, water test results, and rolled-up geological maps.

“I actually know how to read these things, which is helpful to know what’s going on but doesn’t make me feel much better,” said Broberg, a geologist. Then he laughed. “Actually, it probably makes me feel worse.”

His water comes from a well. When Broberg tested it shortly after he purchased the home in 1986, the sample contained nitrates at 8 parts per million, slightly below the EPA limit for the chemical byproducts of commercial and manure fertilizers.

“Every time we tested, there was a higher level of nitrates,” Broberg said.

The tests peaked at 22 parts per million, more than twice the EPA limit.

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

That safe drinking water threshold was set to protect infants from a potentially deadly condition known as blue baby syndrome, that leaves them without enough oxygen in their blood. But a growing body of medical literature links nitrates to other dangers, including birth defects, cancers, and reproductive problems — and at levels below the federal limit.

Broberg is among the tens of thousands of Minnesotans who get their water from private or municipal wells with nitrate levels that exceed the federal limit, some at rates many times that threshold. Nine percent of tested township wells have nitrate levels above the limit. So do 27 percent of samples from Minnesota streams, rivers, and lakes.

A recent analysis by the Environmental Working Group based on records obtained from the state health agency suggests about 150,000 Minnesotans were served by water systems with nitrate levels that exceeded federal health limits in at least one test from 2009 to 2018.

There’s no mystery as to why. Minnesota officials say the contamination comes largely from cropland. Nitrate leaches from agricultural soils into aquifers and waterways.

This isn’t a newly discovered problem. The state has known about it for years, leaning on voluntary measures to stem it.

When regulators finally proposed a set of enforceable rules, a political melee broke out.

State agriculture officials started by simply revising their two-decade-old guidebook of best practices farmers could voluntarily follow to reduce contamination, a move farm groups opposed. One form letter signed by farm groups insisted the 1990s guidelines were just as valid in 2013, despite rising nitrate problems over that period.

By the time Minnesota published the updated guidelines in 2015, state agriculture officials were convinced too few farmers followed such recommendations and many were over-applying fertilizer. Advice alone clearly was not reducing contamination.

Environmental groups urged lawmakers and state authorities to act, as did municipal leaders saddled with millions of dollars in rising water-treatment costs and a group — co-organized by Broberg — representing the 1.2 million Minnesotans who rely on private wells.

Officials started writing fertilizer regulations they could enforce.

“Voluntary participation or compliance was not going to be sufficient to get the kind of really significant change that the state’s situation required,” recalled Mark Dayton, Minnesota’s governor at the time.

Former Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton speaks at the 2016 State Fair to ask Minnesotans to take a Water Stewardship Pledge, and to rethink how water affects their daily lives and how they use it. Jim Mone / AP Photo

The first draft, released in June 2017, would have prohibited many farmers in areas with vulnerable groundwater from applying fertilizer in the fall — when contamination risks rise without plants to suck up the nutrients — or on frozen soil. Exceptions were made for small-grain crops and research.

That kicked off one of the most ferocious fights of Dayton’s political career.

“We ran into stone walls,” he said.

Farmers and agriculture organizations packed public hearings, blitzed their legislators with statements, and filed formal comments that nitrate contamination was overhyped, caused by improperly sited or maintained wells rather than farms, and too costly to deal with the way the proposed regulation required. The Legislature passed a bill to block it. When Dayton responded with a veto, state House and Senate agriculture committees — including lawmakers who also worked as farmers — invoked an obscure provision to stall the rule.

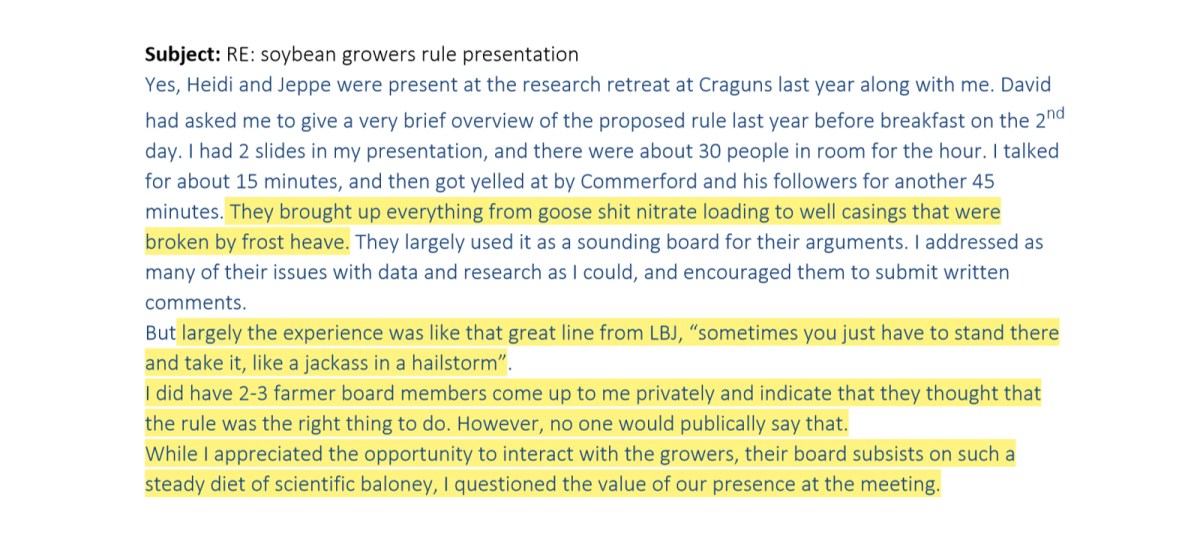

Behind the scenes, the agency’s officials tried to convince politicians that fertilizers were a real and growing public health problem with a large scientific consensus, according to records obtained by Public Integrity and its partners. Those emails also show the agency defending the rule to angry farmers, including some who protested testing city-owned wells for contaminants out of fear that regulations would follow.

In public comments filed during rulemaking, the Minnesota Farm Bureau said voluntary efforts were effective and urged agriculture officials to prove that “elevated nitrate levels are actually the result of current nitrogen fertilizer practices, not due to other nitrogen sources or from fertilizer practices of past generations.”

Early versions of the rule set fertilizer restrictions in large land units, which worried farmers like Bruce Peterson. In just one of his fields, Peterson has a range of soil types and fertilizer needs. Agriculture officials revised it so smaller parts of a field could be restricted without limiting fertilizer application on other parts.

Emails obtained by the Center for Public Integrity and its partners show how the fight over a then-proposed rule that would govern farmers’ use of fertilizer in Minnesota. This internal email from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture suggests exasperation after a meeting with a farm group to discuss the proposed rule.

As the fight dragged on, department employees and staffers with the governor’s office softened their messaging, made more concessions to win over farm groups, and prepared talking points to deal with negative reactions from environmental groups.

During his last days in office, Dayton wrote a letter to his successor, Tim Walz, assuring him that the hard-fought nitrate rule was well-vetted and urgently necessary to protect the environment and public health, records show. Walz signed off, and the revised groundwater protection rule was enacted in 2019. Major farming groups no longer opposed it.

Peterson, in fact, said he expects the rule will have little impact on his operation and most others in southeastern Minnesota. “The vast majority of farmers have kind of gone away from fall nitrogen in these restricted areas already,” he said.

Environmental groups and well-owner organizations say that’s the problem with the rule: It was weakened so much, it does little to protect drinking water.

The state shrunk the number of areas where farmers cannot apply nitrogen fertilizers in the fall or on frozen soil. Other requirements meant to reduce contamination kick in only if nitrate levels near municipal wells worsen, rather than being broadly mandated, and do little to directly control how much fertilizer is applied or where it’s used. Much of the rule’s focus? Voluntary measures.

Agriculture officials also added a provision that requires the state to appoint and consult with a local advisory team as it responds to nitrate problems. Lost in the final rule: protections for privately owned wells like Jeff Broberg’s.

“It’s a whitewash,” Broberg said. “They basically regulated what was already being done.”

No easy answers

Bruce Peterson harvests grain in southeastern Minnesota, but one of the fields he leases was once a turkey farm. Though the birds were shipped out years ago, the lanky farmer can still pinpoint the exact spots they used to roam by pulling up a digital map on a laptop.

“We’ve collected yield data probably,” he said, “since the mid-’90s.” He adjusted the screen and clicking a multicolored map that shows dense corn and soybean growth in places where the turkeys deposited organic fertilizer. “Everything is grid-sampled.”

Corn and soybean farmer Bruce Peterson uses historical yield data and soil samples to decide where to apply fertilizer on his farm in Northfield, Minnesota. Joe Wertz / Center for Public Integrity

Software combining past harvest results with current soil samples creates digital maps that divide his 8,000-acre operation into smaller zones. The data uploads to a computer in the cab of Peterson’s tractor, which syncs up with GPS and automatically adjusts the rate fertilizer is applied as he drives over the cropland. Randy Souder, the Iowa farmer, uses a similar system.

Peterson says the technology hasn’t reduced his total fertilizer use, but the data-driven approach means he’s getting more crops per pound of nitrogen. Increasingly, farmers are adjusting fertilizer to give the most productive parts of their fields an extra dose and going lighter in places where crops are less productive. This approach helps them save money, has reduced fertilizer overapplication, and limits a source of reactive nitrogen that otherwise might contaminate water or become a greenhouse gas.

Agriculture groups point to these and other practices that boost farm profits while reducing environmental damage when they argue against mandates imposed on other polluting industries.

Even so, half the nitrogen applied as fertilizer is not used by crops and escapes into the environment, research shows. And though more efficient uses of nitrogen have increased across the U.S., there’s limited room for improvement. That’s because more and more fertilizer is required if global farm production doubles by 2050 as forecasted to keep up with population growth.

The targeted fertilizing that Peterson does is mainstream, but fewer farmers are employing other conservation practices that can prevent agricultural fertilizer from becoming a climate and environmental hazard.

Brent Larson is one of the outliers.

As the persistent rain soaking his northern Iowa farm paused one morning in late June, Larson snatched a spade and waded into a green quilt of grass. In the distance behind him, a corn ethanol refinery puffed out steamy fingers of vapor as a steady stream of 18-wheelers lined up to empty their trailers.

He slowed every now and then to jab at the earth. Suddenly, he stopped. Clearing the tip of the shovel with his hand, Larson pulled a clump close to his face and then disappeared into the waist-high thicket.

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

“That’s an earthworm hut right there,” he said, pointing to a mound rising above the dark soil.

At night, the worms wriggle to the surface to feast, pulling remains of plants into the soil and decomposing them. “They do the tillage for me,” Larson said. “They put the crop residue in the soil where it belongs.”

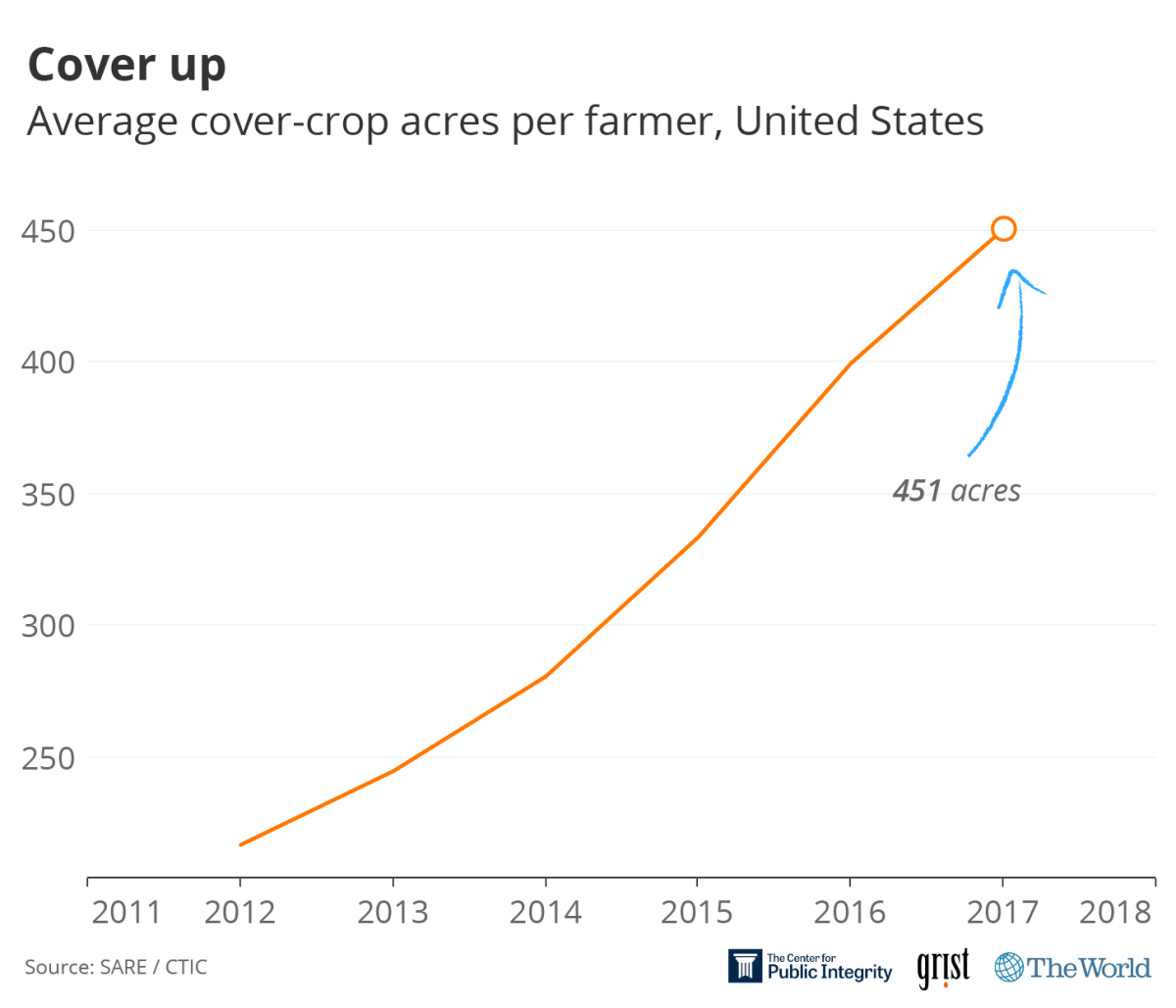

The amount and condition of that residue is crucial, and much of it comes from rye, a cover crop Larson buys and plants but will never sell.

Rye is a time-release nitrogen sponge. As it grows, the rye sops up excess nitrogen before it escapes into the air or water. After the rye dies and decomposes, bacteria squeeze the nitrogen back into the soil, fertilizing later crops. Cover crops are also a magnet for microorganisms that process nitrogen into fertilizer, and they have other benefits, from preventing soil erosion to smothering weeds.

All this means Larson can apply less fertilizer, and less of his nitrogen will break down into compounds that contaminate water, attack the ozone layer, and heat the planet.

Larson tills his cropland into narrow strips instead of overturning entire fields, another measure that preserves nitrogen-storing rye residue on his fields. Strip-tilling also makes it possible to drive a tractor between the rows and inject precise amounts of liquid fertilizer into both sides of his crops instead of spraying it over the entire field.

Larson said his corn and soybean yields increased as he cut back on fertilizer. Tests of the water running off his cropland, meanwhile, suggest the amount of nitrate in it is low.

“It makes sense socially and economically,” he said.

But only a small share of farmers plant cover crops and regularly use tillage practices that can reduce the environmental effects of fertilizers, though that count is rising with some crops in certain regions.

The USDA has increased spending to set aside farmland for conservation and on programs to train and equip farmers for practices that reduce nitrogen pollution.

Still, long-lasting prairies and grasslands, which have deep roots that can suck up excess nitrogen from soil and water, are disappearing. At the same time, following market signals and federal subsidies, American farmers grew fewer acres of small grains like barley, oats, rice, and sorghum and more fields of fertilizer-hungry corn, which has a shorter lifespan and shallower roots.

As climate change brings more weather extremes, it’s likely that improved soil and fertilizer management techniques will have even less of an effect for many regions in the future, said Matt Liebman, a professor and chair of the sustainable agriculture program at Iowa State University.

Solving the problem, he said, requires rethinking not only how but what America farms.

“Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois are a trainwreck this year because of the rain,” he said in the summer of 2019. The current system of rotating between corn and soybeans, he said, “is not going to cut it.”

‘Every farm is a chemical factory’

At the dawn of the 20th century, entrepreneurs and governments raced to find an industrial process to turn atmospheric nitrogen into commercial compounds. The Nobel Prize-winning method that prevailed — still the principal process used to create more than 100 million tons of the element for fertilizer in 2018 — is a chemical reaction of nitrogen and hydrogen that produces not only fertilizers but also explosive weapons.

This dual purpose meant nitrogen synthesis was synonymous with national security. The U.S. government subsidized nitrogen producers under “arms-to-farms” initiatives that supplied munitions for wars and fertilizers during peacetime.

In 1928, then-Agriculture Secretary William M. Jardine wrote that “every farm is a chemical factory.” As the USDA promoted fertilizer-intensive agriculture, fertilizer use and crop yields boomed, especially in the latter part of the 20th century. Less than half of U.S. cornfields were fertilized with commercial nitrogen in 1950. Today, 99 percent of cornfields are.

In the early 20th century the U.S. government promoted fertilizer use to farmers across the country. Above, a farmer sits by a sack of nitrogen fertilizer in San Augustine, Texas, in 1939. Russell Lee / Library of Congress

As invested as the federal government was in creating the fertilizer industry, it has taken a back seat in managing its downsides — even as they worsen.

Stricter federal regulations on greenhouse gas look unlikely in the short term. Regardless, CF Industries Holdings, the largest U.S. nitrogen fertilizer producer, identified that as a “significant” business risk in financial filings. Mosaic, another big producer, identified similar risks and said the multistate effort to limit agricultural runoff and reduce the Gulf dead zone could hurt its business.

The bigger issue? The U.S. market could be maxed out. Fertilizer companies are looking to other, even more lightly regulated markets where they could see the same explosive growth they once had here. In filings and remarks to investors, industry giants point to profitable, long-term trends for fertilizer sales: population growth, higher meat consumption, and more biofuels — particularly in developing countries.

“The U.S., Europe, and Brazil are already using enough nitrogen,” said Seth Goldstein, an analyst with investment research firm Morningstar. “Africa will likely be the area of largest nitrogen demand growth going forward.”

The potential for sharply expanding global fertilizer use — and more harmful climate effects — has scientists sounding alarms.

In October, more than 200 scientists signed an open letter that urged world leaders to act immediately to reduce nitrogen pollution. It’s threatening the health of humans, animals, and plants, they said, but isn’t prioritized in environmental policies focused on carbon dioxide. Letter author Mark Sutton, a U.K. environmental scientist and former chair of the International Nitrogen Initiative, said there’s no way to meet the goals laid out in the Paris Climate Agreement without addressing nitrogen pollution.

“If we want to beat climate change, air pollution, water pollution, biodiversity loss, soil degradation and stratospheric ozone depletion, then a new focus on nitrogen will be vital,” Sutton wrote in the letter to the secretary-general of the United Nations. “The present environmental crisis is much more than a carbon problem.”

International limits have led to steep reductions of other dual-impact gases, but nitrous oxide emissions continue to increase.

A tank of anhydrous ammonia, a common nitrogen fertilizer, sits outside the River Country Cooperative near Hastings, Minnesota. Joe Wertz / Center for Public Integrity

The Montreal Protocol — signed by every country in 1987 and regarded as the most effective international environmental agreement — phased out the production and use of chlorofluorocarbons and other ozone-depleting substances, but it didn’t set limits on nitrous oxide.

That’s now the planet’s dominant ozone-depleting gas.

Later treaties, including the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2016 Paris Agreement, called for nitrous oxide reductions. The U.S. did not join the former and is in the process of dropping out of the latter.

The Montreal treaty worked “because the sources were industrial. Few actors, simple system,” Sutton said. By comparison, he said, cutting nitrous oxide “means transformation of society.”

So far, he said, the largest reductions to fertilizer side effects are in places such as Denmark and the Netherlands — countries with enforceable rules.

“The scientists I speak to say they believe that this would never have happened unless they’d have had mandatory action,” Sutton said. “There clearly has to be a role for regulation if countries are serious about making progress.”

Zach Goldstein contributed to this story.

This story was published in partnership between Grist, the Center for Public Integrity — a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust — and The World, a radio program that crosses borders and time zones to bring home the stories that matter.