Whenever I talk about how we might feed ourselves more equitably and sustainably, I find myself returning to the pie metaphor. Our choices for ending hunger, in pie-language, are: bigger pie, fewer forks, and better manners.

There’s also one more trick we could try: smaller forks. That is, we can eat less — or choose food with a smaller environmental footprint.

There are two main ways to make our forks smaller: eat fewer calories (duh), and eat less meat. Meat is just not as efficient: It takes a bunch of plant calories to produce one meat calorie. (Though when animals are eating food that humans can’t, namely grass, and converting it into steaks, it defies that logic.)

As environmental scientist Jonathan Foley put it, in his much-celebrated prescription for feeding the world:

It would be far easier to feed nine billion people by 2050 if more of the crops we grew ended up in human stomachs. Today only 55 percent of the world’s crop calories feed people directly; the rest are fed to livestock (about 36 percent) or turned into biofuels and industrial products (roughly 9 percent).

This is actually a subset of “better manners.” Right now we live in an upside-down world where the people who get the least food are the ones who are doing the most manual labor. (They’re also the most likely to suffer from infectious disease.) And in the most developed countries, we have technology taking care of all our physical, calorie-burning labor, while we sit on our butts all day and drink everyone else’s milkshake.

The very first thing people tend to buy when their economic situation improves is more expensive food. Richer countries — particularly the ones exporting pop music and movies, and generally radiating coolness — are the foodie role models. That means, terrifyingly, that as people around the world become more affluent, they are looking to us for examples of what to do with their newfound wealth.

So it really is time for us to start using smaller forks. Already, there are twice as many overweight people globally as there are hungry people.

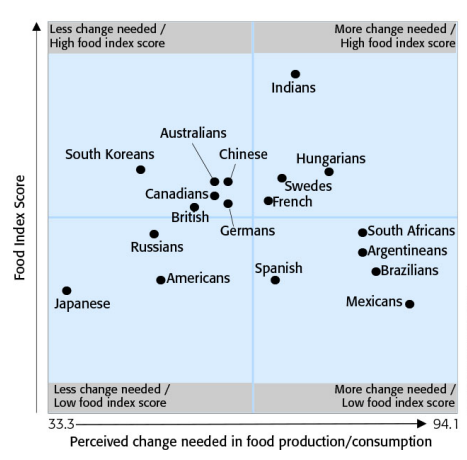

The major problem here is that many of the people eating up more than their share of the earth’s pie are convinced that they aren’t doing anything wrong. There’s a really depressing graph that Globescan made in a survey it did for National Geographic. The pollsters asked people around the globe how much they felt we needed to change the food system to feed the growing population. Globally, 63 percent of people said we need large, or very large, changes. But not everyone. In fact, many of the people with the most environmentally intensive diets felt the least urgency for change.

You want to be near the top of this graph: A higher food index score indicates more sustainable eating. On the horizontal axis, the countries farther to the right recognize the need for change. The United States, Russia, and Japan are in the lower-left quadrant — the quadrant of destructive cluelessness. As individual eaters, we’re like the blithe, rambunctious toddlers at the table, happily putting our hands in everyone else’s food, and throwing the bowls on the floor.

The closer I looked at the potential for shrinking forks, the more it seemed both important and impossible. So I called up Michael Pollan, who has been writing about food culture for over a decade, to see if he had pointers for inciting change. “I’m not pessimistic,” he said. “We think of changing food culture as the hardest thing to do, but we’ve seen so many changes to food, many driven by marketing, many driven by fads and fears. Americans have become very open to changes in food.”

Our willingness to throw out our old food traditions and try something new led to the rise of fast food and is partially responsible for the obesity epidemic. But, now, that same flexibility also offers an opportunity to change for the better. That would mean eating less, enjoying it more, and making meat a rare treat.

“I can imagine a change where we were eating less and celebrating quality rather than quantity,” Pollan said. “It’s a funny accident of American history that we only celebrate quantity. You may be too young to remember, but on Wednesdays newspapers used to have a supplement advertising the grocery stores, and the bargains were always cast in terms of quantity: Three pounds of tomatoes for $1.50.”

Of course, in any value proposition, quality actually matters as much as quantity, and when you are talking about bringing pleasure to life, quality probably matters more.

Here are Pollan’s fork-shrinking suggestions, which I’ve interpreted and expanded upon.

Celebrate meat, and eat it less frequently

The idea that meat is special goes back to our hunter-gatherer days, and, among people who like their fix once a day, it’s probably not going away anytime soon. But we could use that sense of specialness, and eat meat with more ritual, much less frequently. The idea of meatless Mondays is a good start — it provides something for institutions to organize around. It has also been significant enough to provoke the outrage of the meat industry and farm-state politicians. “It would be really interesting to see high-end restaurants doing a meatless day,” Pollan said. “If Chez Panisse, or David Chang, or Tom Colicchio tried that.”

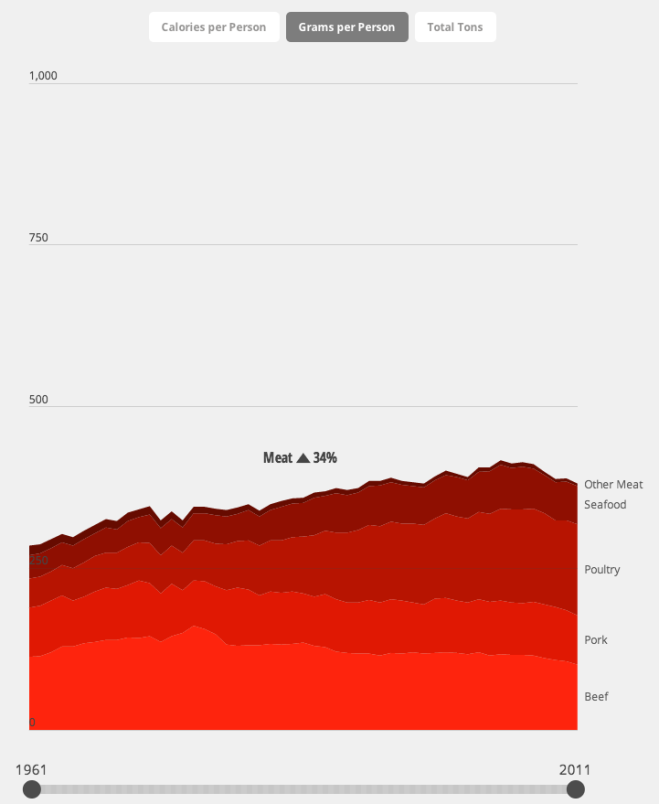

For what it’s worth, America may actually be changing in this regard. This graph from National Geographic suggests we hit peak meat in 2004:

Use the tools of the food industry for good

The food industry knows how to change food culture. Behavioral economist Brian Wansink, director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab, has done lots of fascinating work to demonstrate how we might use this power to help us eat less.

“We think we are in control, but if we just get a smaller plate, we eat less,” Pollan said.

School lunchrooms are already reorganizing their buffets so that students come to the vegetables first, when there’s lots of room on the plate; that makes students eat more salad and less sugary snacks. There’s a potential for food companies to profit by helping us outwit our irrational food choices, rather than by exploiting them.

We know that kids respond to advertising, so Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move campaign took some of those techniques that had proved successful and appropriated them — licensing the use of Sesame Street characters, for example.

Meat substitutes

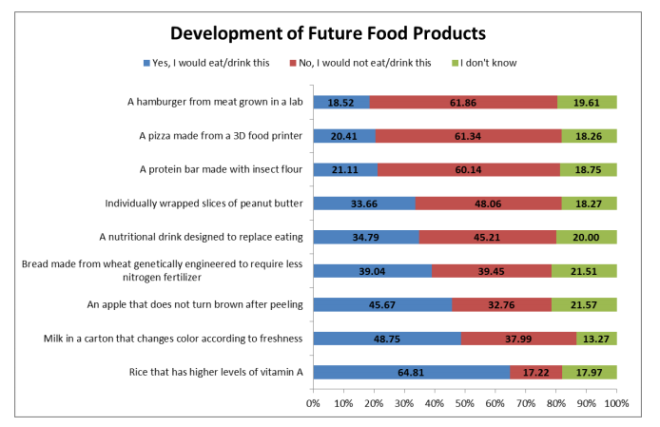

There are several high-tech startups trying to produce a replacement for meat, which could provide environmentally friendly protein. They face a substantial hurdle, though. A full 61.8 percent of respondents to the Oklahoma State Food Demand Survey said they wouldn’t eat a hamburger from meat grown in a lab.

Maybe “grown in a lab” has too much ick factor. What if you changed the wording, Pollan wondered, and asked people, “Would you eat a hamburger made from pea protein?”

Another problem is that our idea of hamburgers is wedded indelibly to beef. “If meat substitutes succeed, they will succeed either on the basis of price or for ideological reasons,” Pollan said. “If the reason we like meat is the idea of meat, and the prestige it connotes, we’re not likely to switch.”

But if these companies can produce a passable meat substitute cheaply, it has tremendous potential. “They should be aiming for the lower end of the market,” Pollan said. “You know, if you take apart a McDonald’s hamburger, get rid of all the toppings and just taste the meat, that’s not an amazing product. It shouldn’t be hard to exceed that.”

It might be very hard to make a delicious vegetarian roast chicken, but it wouldn’t be so hard to make faux-chicken cubes for a canned soup. That would be classic bottom-up disruption, in the Clayton Christensen model.

Other ideas

I wrote before about ecologist David Tilman’s idea for a sort of Nobel Prize for low-impact recipes. He’d like to have a national contest each year for a delicious dish that’s healthy and environmentally friendly.

One of the places we might go to look for those dishes is India. There’s something interesting going on in that country. It’s the one place where meat consumption hasn’t increased along with wealth, and Indians are more likely than any other nationality to say that food is an essential part of their culture. India is like the anti-America when it comes to food; we should probably be imitating them.

When I cook virtuously, it’s often pretty spartan: Lentils and brown rice — bland Northern Californian hippie food. And I’m realizing, there’s no reason it has to be that way. Why can’t my lentils be as good as Indian dal, or Ethiopian mesr wat?

The nice thing about this is that no one has to wait for lab-grown meat, or virtuously profitable food companies. You can all start right now: Eat less food, and spend the money you save on higher quality. If the rest of America doesn’t join in, you shouldn’t feel like a sucker. After all, you’ve just made yourself healthier.