For years, U.S. nutritional policy has been flailing. You’ve probably already heard about the somewhat revolutionary recommendations on cholesterol and coffee that emerged last week from a federal nutrition advisory committee. The panel published a review of nutritional science that is one stop on the bureaucratic road toward preparing a new set of national dietary guidelines.

Every five years, we get a new set of these guidelines from the government, sometimes containing information that contradicts the previous versions. In between, we get a continuous torrent of food fads and diet books. You’d think we’d tune out all this noise, but we don’t; meanwhile, we keep getting fatter and less healthy.

There’s got to be a better way, and Brazil may have found it — by ditching the scientific jargon and instead offering some simple wholesome advice.

The reason nutrition is so acrimonious and confusing is that it’s preposterously hard to study. To get solid data, you need to focus on one thing at a time: Do a randomized controlled study on what happens when you increase one particular type of fat in diets. But these precise studies are often not applicable to the grand and complicated mess of human health. The effect of a nutrient may depend on the other molecules in the meal, on the time of day you eat it, on your genetics, on your lifestyle, on your gut bacteria, on your age — I could go on.

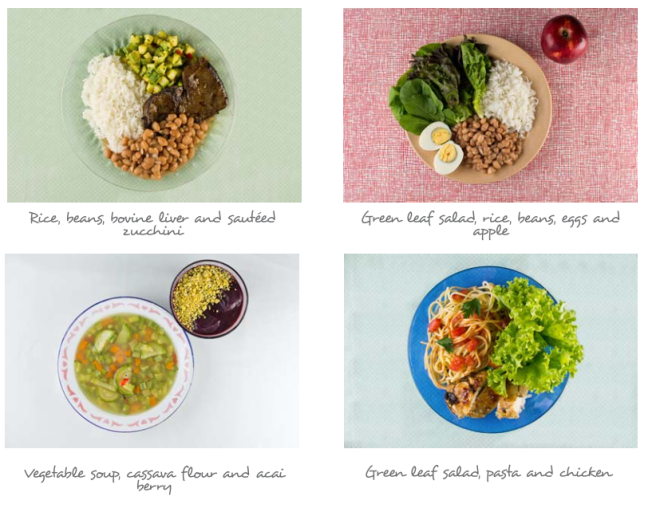

One solution would be to stop focusing on the minutia, and instead make some simple common-sense recommendations. That’s the method that Brazil has adopted. Instead of talking about saturated versus polyunsaturated fat, the Brazilian guide has one “golden rule” that anyone can understand and follow: “Always prefer natural or minimally processed foods and freshly made dishes and meals to ultra-processed foods.”

There’s also other advice on how (rather than what) to eat: “Prefer eating with family, friends, or colleagues.” And: “Make the preparation and eating of meals privileged times of conviviality and pleasure.” The guidelines exchange precise detail for wonderfully touchy-feely wisdom. The suggestions are distinctly similar to the ideas proposed by Michael Pollan in In Defense of Food.

I spoke with Carlos Monteiro, a doctor based at University of Sao Paulo, whose Center for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition conceived of this guide. He explained that the origins of this unusual approach in confusion over counterintuitive data based on what people were cooking and eating at home.

Q. How did you from go looking at specific nutrients to a holistic focus on eating?

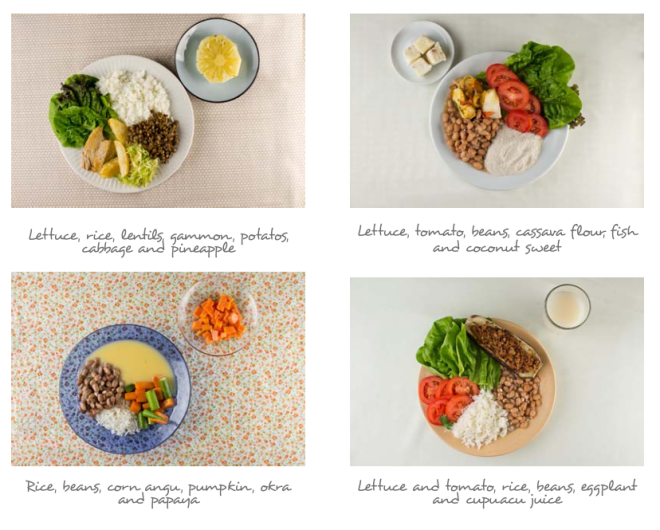

A. One of the first things I noticed in Brazil was that foods like sugar and vegetable oils — that common sense could say are causes of obesity — were in decline. People were buying less and less vegetable oils, and even sugar. And also foods like rice and beans, which are very common foods in Brazil, and even some items like milk and meat were in decline — not so fast as rice and beans, but they were in decline.

Q. So Brazil had an obesity problem growing at the same time it was consuming less of these foods.

A. What we realized is that people were simply cooking less. They had used sugar and oils to prepare food and dessert. And these elements of the diet were being replaced by everything that was ready-to-eat, let’s say, very modern products. It was not cheese or salted meat, but it was certain types of products with lots of ingredients and very little whole food.

Q. That’s what you’re calling ultra-processed food?

A. Yes, we created the definition of ultra-processed foods to describe these.

The fat and the sugar that people were not eating — they were eating much more through these ultra-processed products. So we came up with a proposal to classify foods according to four categories — minimally processed foods, processed foods like cheese and bread, ultra-processed foods, and also the culinary ingredients, which is a very specific type of food that you don’t eat by itself, you just use it to cook and prepare minimally processed foods.

That’s a very important difference between our guidelines and other guidelines that refer to oils and sugars as something you need to eliminate from our diet. Without oil and sugar, at least in Brazil, you cannot cook and prepare meals.

Q. I think the point is that you need to communicate to the people, and if you are saying to the people eat less oil and sugar, that’s good advice, but it’s hard for them to apply that to the oil and sugar in the ultra-processed foods that are becoming a bigger and bigger part of their diet. The oil and the sugar that people actually see when they cook is not the problem. Is that right?

A. Exactly. Used in small amounts the oil and table sugar that you use to cook — it’s not only useful, it’s essential. Probably in any cuisine in the world you cannot cook without some kind of fat or oil.

Q. How did you decide that ultra-processed foods were the category to target?

A. We used recent surveys of what people eat — 30,000 people considering two days of their diet. And we came to the conclusion that the more people used the ready-to-consume products, the more problems they had with the diet. Not just in terms of salt and sugar, but also in terms of unhealthy fats, energy density, essential nutrients, fiber, bioactive compounds, antioxidants — everything goes in the wrong direction.

On the other side, people who preserve that pattern of having freshly prepared dishes had the best diet. The good news is that these people are not the richest. They have lower income, many of them live in isolated places in Brazil.

Q. Are you saying that all processed foods are bad? I can anticipate the criticism — I’m grateful that my mother isn’t grinding corn on her hands and knees.

A. This is important. We are not saying you can’t eat any processed food. On the contrary, what we say is base your diet on minimally processed foods. Take rice and beans — they are processed, you have industries behind these foods. Processed foods like oil and even sugar and salt, they are all necessary in moderation. Processed foods, bread and cheese, again we say they have a space.

What we say people should avoid is a very specific set of products that represent 30 percent of calories for the average Brazilian. For the United States, it is double this.

Q. I was just reading this piece in Vox, and the last line asks why can’t America do the same thing as you. And the answer seems clear to me: The politics of food here only allow for small legalistic statements. A new set of recommendations came out today and the meat industry is already frothing at the mouth. How did you get this passed? Are the food politics different in Brazil?

A. It’s a very interesting question — we are still thinking about this. We worked on this for three years and until the last minute, we were not sure that we would get these published. Brazil is not different from other places where the food industry is very important.

When we went for a public consultation — that’s the normal process in Brazil for new policies [like U.S. public comment periods] — we received about 3,000 suggestions. The comments from the food industry were very negative. They basically didn’t like anything. They said they would prefer the old guia. Why didn’t we use portions or serving sizes? Why aren’t we saying everything is good in moderation? Why are we so radical on ultra-processed products? They also didn’t like the idea that the guidelines say it’s not the solution to take some salt out of a product. This in particular they hate. They say, ‘Whoa, we are doing our best to improve our products and you are saying that these premium products are not the solution.’

But there were even more comments from civil society. Many people, particularly people more linked to food insecurity, suggested we include that these minimally processed foods are also very good for the environment, for equity, and the fairness of the economic system. And we made this change.

We presented this to the Ministry of Health. At the last minute, there was pressure on the Minister of Health and the launch was postponed. We had tickets to go to Brasilia and at the last minute the launching was cancelled. But it was cancelled because the plan had been for the director of nutrition to handle the launch, but it turned out that the minister of health wanted to do it personally in the most important setting, the National Health Council.

So the guide wasn’t supported by the industry, but there was a lot of support from other areas. That’s how politics works.

Q. Here, it’s really hard to get a recommendation through without bulletproof science supporting it. In part because we’ve made recommendations in the past that turned out to be misguided.

A. The food industry is saying, we accept recommendations if they are supported 100 percent by randomized controlled trials. That’s something we never would get if we look at actual meals. We used the best evidence we could get, but we didn’t use only randomized controlled trials, because if you use only randomized controlled trials then you can only make recommendations about nutrients. This is a trap.

Q. One factor that actually could move the political impasse here would be the success of your experiment in Brazil, if it works. You won’t have randomized controlled trials, I assume, but there will be evidence generated by this policy change. Are there people studying this?

A. Yes, of course. We have the baseline data so it will be no problem to follow and see what happens with the diet. But what we are very much engaged in now is the dissemination of the recommendations. We want to train the health workers — Brazil has a huge family health program — we want them to bring this message when they visit people. The other setting is schools. And there will need to be other policies, like taxation, like control of advertising. If you don’t control marketing, it’s much more difficult to get the messages of the guide to people.

We made some minor changes to this interview for clarity.