This story was produced by Grist and co-published with Slate.

When Henri Kunz was growing up in West Germany in the 1980s, he used to drink an instant coffee substitute called Caro, a blend of barley, chicory root, and rye roasted to approximate the deep color and invigorating flavor of real coffee. “We kids drank it,” Kunz remembered recently. “It had no caffeine, but it tasted like coffee.”

As an adult, Kunz loves real coffee. But he also believes its days are numbered. Climate change is expected to shift the areas where coffee can grow, with some researchers estimating that the most suitable land for coffee will shrink by more than half by 2050, and hotter temperatures will make the plants more vulnerable to pests, blight, and other threats. At the same time, demand for coffee is growing, as upwardly mobile people in traditionally tea-drinking countries in Asia develop a taste for java.

“The difference between demand and supply will go like that,” Kunz put it during a Zoom interview, crossing his arms in front of his chest to form an X, like the “no good” emoji. Small farmers could face crop failures just as millions of new people develop a daily habit, potentially sending coffee prices soaring to levels that only the wealthy will be able to afford.

To stave off the looming threats, some agricultural scientists are hard at work breeding climate-resilient, high-yield varieties of coffee. Kunz, the founder and chair of a “flavor engineering” company called Stem, thinks he can solve many of these problems by growing coffee cells in a laboratory instead of on a tree. A number of other entrepreneurs are taking a look at coffee substitutes of yore, like the barley beverage Kunz grew up drinking, with the aim of using sustainable ingredients to solve coffee’s environmental problems — and adding caffeine to reproduce its signature jolt.

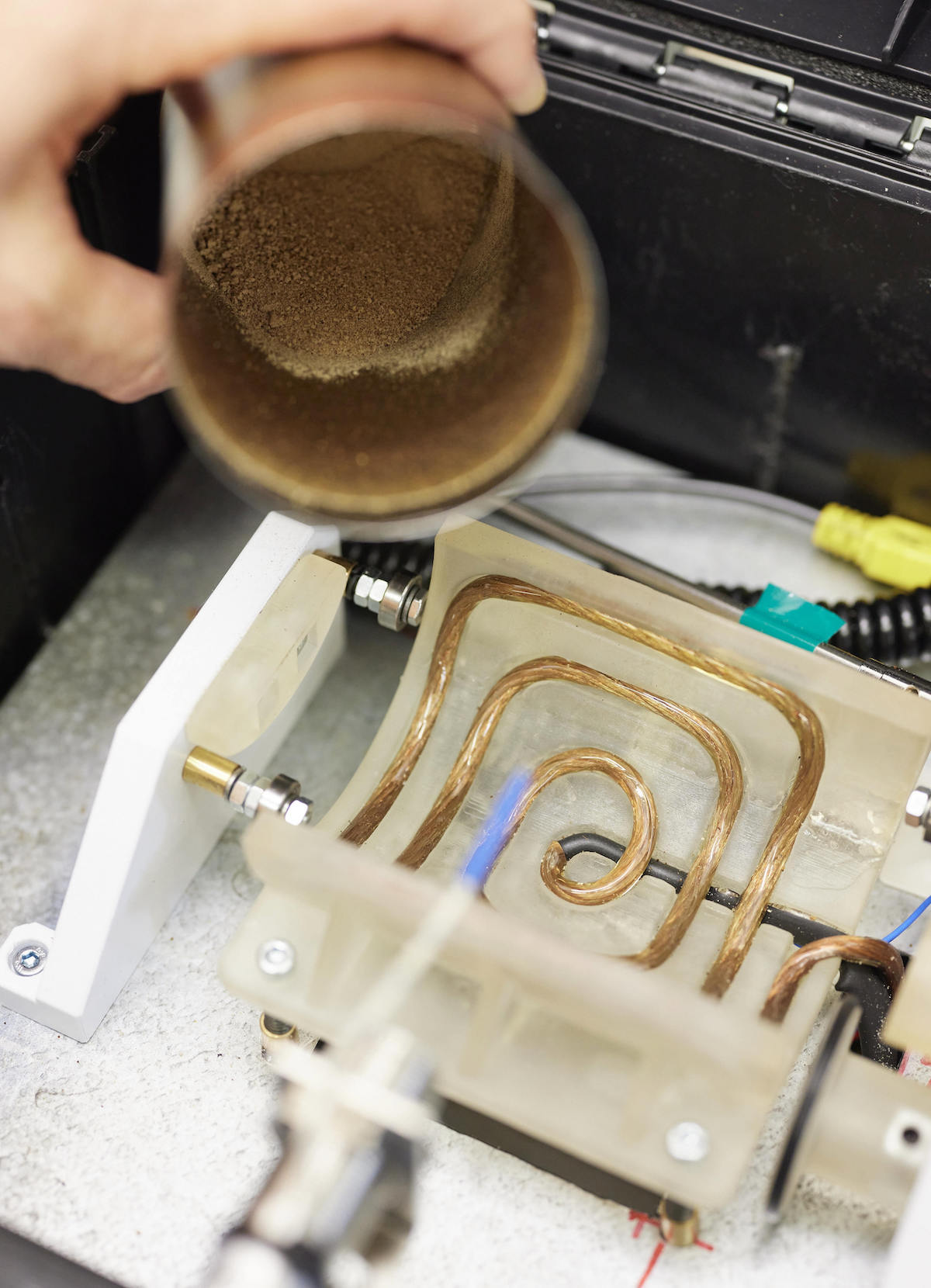

Stem’s cell-cultured coffee powder is prepared, roasted, and extracted. Courtesy of Jaroslav Monchak / STEM

A crop of startups, with names like Atomo, Northern Wonder, and Prefer, is calling this category of throwbacks “beanless coffee,” even though in some cases their products contain legumes. Beanless coffee “gives you that legendary coffee taste and all the morning pick-me-up you crave, while also leaving you proud that you’re doing your part to help unf–k the planet,” as the San-Francisco based beanless coffee company Minus puts it. But it’s unclear whether coffee drinkers — deeply attached to the drink’s particular, ineffable taste and aroma — will embrace beanless varieties voluntarily, or only after the coming climate-induced coffee apocalypse forces their hand.

Coffea arabica — the plant species most commonly cultivated for drinking — has been likened to Goldilocks. It thrives in shady environments with consistent, moderate rainfall and in temperatures between 64 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit, conditions often found in the highlands of tropical countries like Guatemala, Ethiopia, and Indonesia. Although coffee plantations can be sustainably integrated into tropical forests, growing coffee leads to environmental destruction more often than not. Farmers cut down trees both to make room for coffee plants and to fuel wood-burning dryers used to process the beans, making coffee one of the top six agricultural drivers of deforestation. When all of a coffee tree’s finicky needs are met, it can produce harvestable beans after three to five years of growth, and eventually yields 1 to 2 pounds of green coffee beans per year.

If arabica is Goldilocks, climate change is an angry bear. For some 200 years, humans have been burning fossil fuels, spewing planet-warming carbon dioxide into the air. The resulting floods, droughts, and heatwaves, as well as the climate-driven proliferation of coffee borer beetles and fungal infections, are all predicted to make many of today’s coffee-growing areas inhospitable to the crop, destroy coffee farmers’ razor-thin profit margins, and sow chaos in the world’s coffee markets. That shift is already underway: Extreme weather in Brazil sent commodity coffee prices to an 11-year high of $2.58 per pound in 2022. And as coffee growers venture into new regions, they’ll tear down more trees, threatening biodiversity and transforming even more forests from carbon sinks into carbon sources.

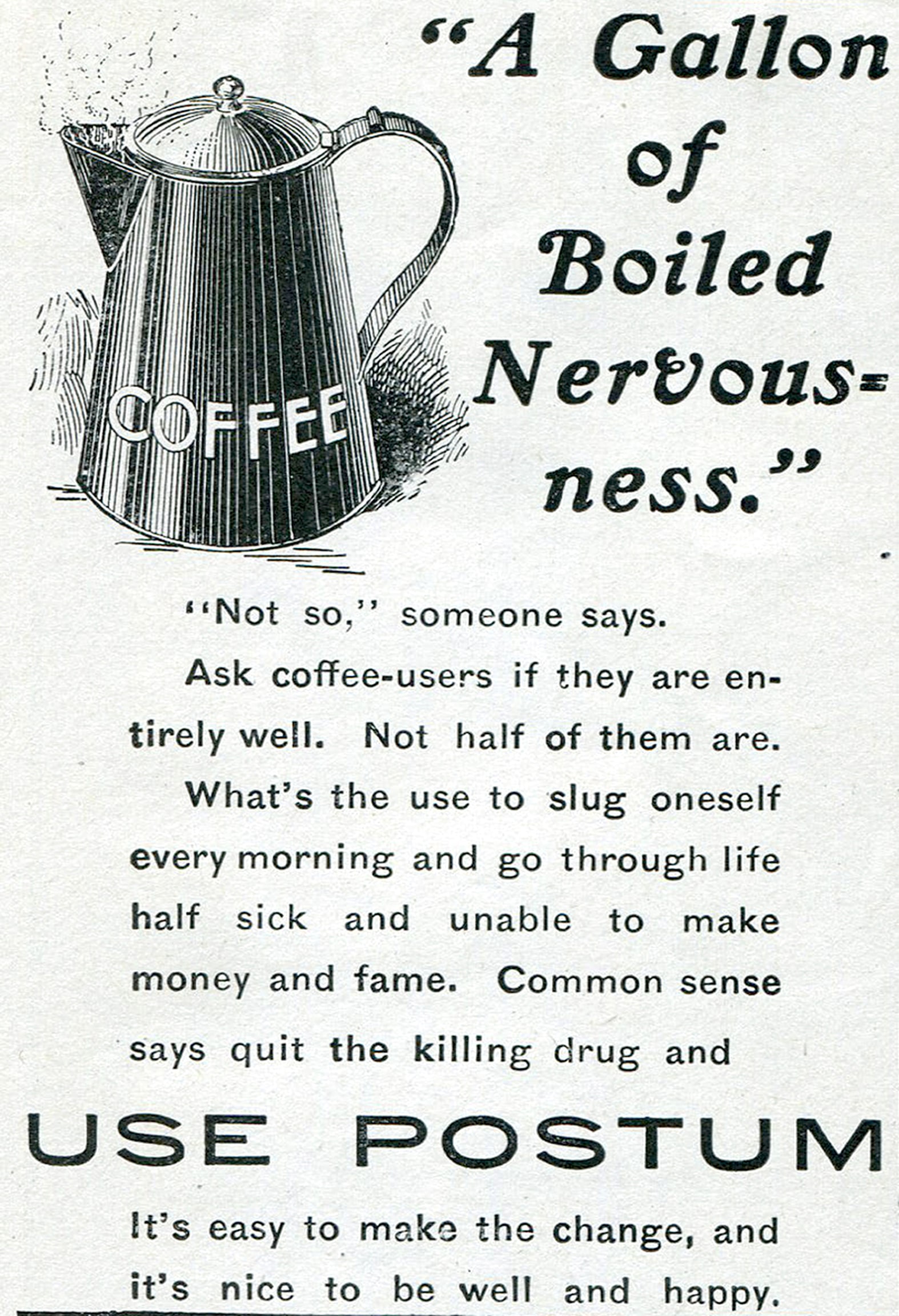

At many times in the past, coffee has been out of reach for most people, so they found cheaper, albeit caffeine-free, alternatives. Caro and other quaint instant beverage mixes, like Postum in the U.S. and caffè d’orzo in Italy, were popular during World War II and in the following years, when coffee was rationed or otherwise hard to come by. But the practice of brewing non-caffeinated, ersatz coffee out of other plants is even older than that. In the Middle East, people have used date seeds to brew a hot, dark drink for hundreds or perhaps thousands of years. In pre-Columbian Central America, Mayans drank a similar beverage made from the seeds of ramón trees found in the rainforest. In Europe and Western Asia, drinks have been made out of chicory, chickpeas, dandelion root, figs, grains, lupin beans, and soybeans. These ingredients have historically been more accessible than coffee, and sometimes confer purported health benefits.

Today’s beanless-coffee startups are attempting to put a modern spin on these time-honored, low-tech coffee substitutes. Northern Wonder, based in the Netherlands, makes its product primarily out of lupin beans — also known as lupini — along with chickpeas and chicory. Atomo, headquartered in Seattle, infuses date seeds with a proprietary marinade that produces “the same 28 compounds” as coffee, Atomo boasts. Singapore-based Prefer makes its brew out of a byproduct of soymilk, surplus bread, and spent barley from beer breweries, which are then fermented with microbes. Minus also uses fermentation to bring coffee-like flavors out of “upcycled pits, roots, and seeds.” All these brands add caffeine to at least some of their blends, aiming to offer consumers the same energizing effects they get from the real deal.

“We’ve tried all of the coffee alternatives,” said Maricel Saenz, the CEO of Minus. “And what we realize is that they give us some resemblance to coffee, but it ultimately ends up tasting like toasted grains more than it tastes like coffee.”

In trying to explain what makes today’s beanless coffees different from the oldfangled kind, David Klingen, Northern Wonder’s CEO, compared the relationship to the one between modern meat substitutes and more traditional soybean products like tofu and tempeh. Many plant-based meats contain soybeans, but they’re highly processed and combined with other ingredients to create a convincing meat-like texture and flavor. So it is with beanless coffee, relative to Caro-style grain beverages. Klingen emphasized that he and his colleagues mapped out the attributes of various ingredients — bitterness, sweetness, smokiness, the ability to form a foam similar to the crema that crowns a shot of espresso — and tried to combine them in a way that produced a well-rounded coffee facsimile, then added caffeine.

By contrast, traditional coffee alternatives like chicory and barley brews have nothing to offer a caffeine addict; Atomo, Minus, Northern Wonder, and Prefer are promising a reliable daily fix.

“Coffee is a ritual and it’s a result,” said Andy Kleitsch, the CEO of Atomo. “And that’s what we’re replicating.”

Each of these new beanless coffee companies has a slightly different definition of sustainability. Northern Wonder’s guiding light is non-tropical ingredients, “because we want to make a claim that our product is 100 percent deforestation free,” Klingen said. Almost all its ingredients are annual crops from Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Turkey, countries whose forests are not at substantial risk of destruction from agriculture. Annual crops grow more efficiently than coffee trees, which require years of growth before they begin producing beans. A life cycle analysis of Northern Wonder’s environmental impacts, paid for by the company, shows that its beanless coffee uses approximately a twentieth of the water, generates less than a quarter of the carbon emissions, and requires about a third of the land area associated with real coffee agriculture.

Michael Hoffmann, professor emeritus at Cornell University and the coauthor of Our Changing Menu: Climate Change and the Foods We Love and Need, said he was impressed with Northern Wonder’s life cycle analysis, which he described as nuanced and transparent about the limitations of its data. He praised the idea of using efficient crops, saying that some of those used by beanless coffee companies “yield far more per unit area than coffee, which is also a big plus.”

But there are trade-offs associated with higher yields. Daniel El Chami, an agricultural engineer who is the head of sustainability research and innovation for the Italian subsidiary of the fertilizer and plant nutrition company Timac Agro International, pointed out that higher-yield crops tend to use more fertilizer, which is manufactured using fossil fuels in a process that emits carbon. Crops that use land and other resources efficiently can require several times more fertilizer than sustainably grown coffee, he said. For this reason, El Chami just didn’t see how Northern Wonder could wind up emitting less than a quarter of coffee’s emissions.

Other beanless coffee companies are staking their sustainability pitch on their repurposing of agricultural waste. Atomo’s green cred is premised on the fact that its central ingredients, date seeds, are “upcycled” from farms in California’s Coachella Valley. Whereas date farmers typically throw seeds away after pitting, Atomo pays farmers to store the pits in food-safe tote bags that get picked up daily. Atomo’s current recipe also includes crops from farther afield, like ramón seeds from Guatemala and caffeine derived from green tea grown in India, but Kleitsch said they’re looking to add even more upcycled ingredients.

Food waste is a major contributor to climate change, and Hoffmann, the Cornell professor, said repurposing it for beanless coffee is “a very good approach.” Minus, which also uses upcycled date pits, claims its first product, a canned beanless cold brew (which is not yet available in stores), uses 94 percent less water and produces 86 percent less greenhouse gas emissions than the real thing. Those numbers are based on a life cycle analysis that Saenz, Minus’ CEO, declined to share with Grist because it was being updated.

(Atomo expects to release a life cycle analysis this spring, and Prefer is planning to conduct a study sometime this year.)

Despite beanless coffee companies’ impressive sustainability claims, not everyone is convinced that building an alternative coffee industry from scratch is better than trying to make the existing coffee industry more sustainable — by, for instance, helping farmers grow coffee interspersed with native trees, or dry their beans using renewable energy.

El Chami thinks the conclusion that coffee supply will dwindle in an overheating world is uncertain: A review of the research he coauthored found that modelers have reached contradictory conclusions about how climate change will change the amount of land suitable for growing coffee. Although rising temperatures are certainly affecting agriculture, “climate change pressures are overblown from a marketing point of view by private interests seeking to create new needs with higher profit margins,” El Chami said. He added that the multinational companies that buy coffee from small farmers need to help their suppliers implement sustainable practices — and he hoped beanless coffee companies would do the same.

Whether demand for beanless coffee will increase depends a great deal on how much consumers like the taste.

I, for one, enjoyed the $5 Atomo latte that I tried at the Midtown Manhattan location of an Australian cafe chain called Gumption Coffee — the only place on Earth where Atomo is being sold. The pale, frothy concoction tasted slightly sweet and very smooth. Atomo describes its espresso blend as having notes of “dark chocolate, dried fruit, and graham cracker.” If I hadn’t known it was made with date seeds instead of coffee beans, I would have said it was a regular latte with a dash of caramel syrup added.

The Northern Wonder filter blend that I ordered from the Netherlands (about $12 for a little more than a pound of grounds, plus about $27 for international shipping) had to overcome a tougher test: I wanted to drink it black, the way I do my regular morning coffee. I brewed it in my pour-over Chemex carafe, and the dark liquid dripping through the filter certainly looked like coffee. But the aroma was closer to chickpeas roasting in the oven — not an unpleasant smell, just miles away from the transcendent scent of arabica beans. The flavor was also off, though I couldn’t quite put my finger on what was wrong. Was it a lack of acidity, or a lack of sweetness? It wasn’t too bitter, and it left a convincing tannic aftertaste in my mouth. After a few sips, I found myself warming up to it, even though it obviously wasn’t coffee. My Grist colleague Jake Bittle had a similar experience with Northern Wonder, describing the flavor it settled into as “weird Folgers.” If real coffee suddenly became scarce or exorbitantly priced, I could see myself drinking Northern Wonder or something like it. It would certainly be better than forgoing coffee’s flavor and caffeine entirely by drinking nothing at all in the morning, or acclimating to the entirely different ritual and taste of tea.

Klingen concedes that the aroma of beanless coffee needs work. Northern Wonder is developing a bean-like product that, when put through a coffee grinder, releases volatile compounds similar to those that give real coffee its powerful fragrance, like various aldehydes and pyrazines. But beanless coffee could win over some fans even if it doesn’t mimic coffee’s every attribute. Klingen said drinkers often rate his product higher for how much they like it than for how similar it is to coffee. “With Oatly, oat milks or [other] alt milks, there you see the same,” he said. When you ask consumers if oat milk tastes like milk, they say, “‘Eh, I don’t know.’ But is it tasty? ‘Yes.’”

Just as the dairy industry has tried to prevent alternative milk companies from calling their products “milk,” some people raise an eyebrow at the term “beanless coffee.” Kunz — the German entrepreneur who grew up drinking Caro and is now trying to grow coffee bean cells in a lab — takes issue with using the word coffee to describe products made out of grains, fruits, and legumes. “What we do — taking a coffee plant part, specifically a leaf from a coffee tree — it is coffee, because it’s the cell origin of coffee,” Kunz said. Drinks made from anything else, he insists, shouldn’t use the word. Kunz’s cell-cultured coffee product hasn’t been finalized yet and, much like lab-grown meat, faces fairly steep regulatory hurdles before it can be sold in Europe or the United States.

The specter of plant-based meat and dairy looms large over the nascent beanless coffee industry. A slew of startups like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods hit the scene in the mid-2010s with products that they touted as convincing enough to be able to put animal agriculture out of business. But in recent years, these companies have faced declining sales in the face of concerns about health, taste, and price.

Jake Berber, the CEO and cofounder of Prefer, fears something similar could happen to beanless coffee businesses. “My hope for everyone in the industry is to keep pushing out really delicious products that people enjoy so that the whole industry of beanless coffee, bean-free coffee, can profit from that, and we can sort of help each other out,” he said.

Different beanless coffee companies are staking out different markets, with some positioning themselves as premium brands. Saenz wouldn’t say how much Minus wants to charge for its canned cold brew, but she said it will be comparable to the “high-end side of coffee, because we believe we compete there in terms of quality.” Atomo is putting the finishing touches on a factory in Seattle with plans to sell its beanless espresso to coffee shops for $20.99 per pound — comparable to a specialty roast.

“The best way to enjoy coffee is to go to a coffee shop and have a barista make you your own lovingly made product,” Kleitsch said. Atomo is aiming to give consumers a “great experience that they can’t get at home.”

In contrast, Northern Wonder and Prefer are targeting the mass market. Northern Wonder is sold in 534 grocery stores in the Netherlands and recently became available at a leading supermarket in Switzerland. Prefer, meanwhile, is selling its blend to coffee houses, restaurants, hotels, and other clients in Singapore with a promise to beat the price of their cheapest arabica beans. Berber predicts that proposition will get more and more appealing to buyers and consumers in the coming years as the cost of even a no-frills, mediocre espresso drink approaches, and then surpasses, $10. A warming planet will help turn coffee beans into a luxury product, and middle-class customers will get priced out. Then, Prefer’s bet on a climate-proof coffee replacement will pay off.

“We will, in the future, be the commodity of coffee,” Berber said.