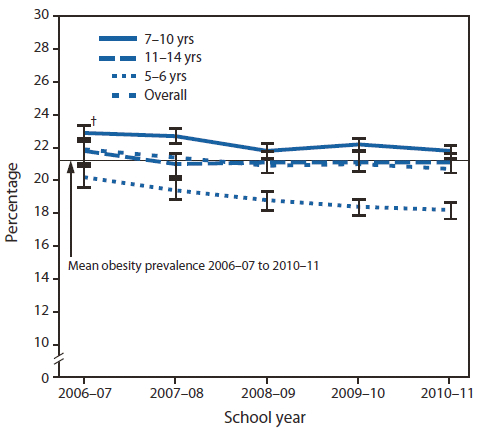

New York City appears to have won a skirmish in its war on childhood obesity. According to a new report out from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), between 2006 and 2011, the obesity rate among children ages 5-14 in New York City dropped by over 5 percent.

New York City appears to have won a skirmish in its war on childhood obesity. According to a new report out from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), between 2006 and 2011, the obesity rate among children ages 5-14 in New York City dropped by over 5 percent.

Obesity is, of course, not so much an ill in itself as a cause of major health problems like heart disease, diabetes, and even some kinds of cancers — diseases from which kids are by no means immune. And it’s also worth remembering that obesity is not the same as being overweight. Obesity starts with a Body Mass Index of 30 or higher. As an example, a child who’s four feet tall isn’t considered obese unless he or she weighs 100 pounds. That’s a lot of extra weight.

Given that most parts of the country have seen obesity rates increase or, at best, plateau, this is a compelling vindication of New York City’s strenuous anti-obesity campaign.

This is, after all, the city that gave us the “Don’t Drink Yourself Fat” media campaign, one of the first major trans-fat bans, and a vigorous attempt to get processed food companies to reduce salt levels in their products. And don’t forget the city’s pioneering chain restaurant calorie labeling law, and, of course, its school food improvements.

Does this reduction tell us what works? Sadly, no. But an interesting twist in these results was suggested to me by Julia Lynch, a University of Pennsylvania political scientist who specializes in public health issues (and, full disclosure, my spouse). She observed that New York City’s success may be the result of the interactions of all the interventions — and that some interventions that don’t on their own appear to reduce obesity (such as calorie labeling) may in fact have an effect when part of a larger campaign.

The point being that if other cities or states want to replicate New York City’s success, they shouldn’t presume that they can cherry-pick the interventions — it might be a case of all or nothing.

Of course, there is some bad news nestled in the good. The bulk of the drop in obesity occurred in predominantly white, low-poverty neighborhoods. Minority children in high-poverty areas showed insignificant drops. This matters a lot because obesity rates tend to be higher in the latter areas — and the food environment far worse.

I also wonder what will happen if we get to a point where obesity has receded so much among middle-income Caucasians that it’s perceived as exclusively a problem for high-poverty, minority communities. Will our commitment to addressing it flag?

Either way, even New York City has its work cut out for it if it’s going to meet Michelle Obama’s Let‘s Move goal of a 5 percentage point reduction in the childhood obesity rate by 2020 [PDF]. The drop measured here is a bit more than 1 percentage point (from 21.9 percent to 20.7 percent) — but that’s almost halfway to the 2015 benchmark of 2.5 percentage points, so we might be on our way!

It’s possible that the Big Apple has picked the low-hanging fruit — and the effort may only get harder from here. Keep in mind, however, that in 1980 the childhood obesity rate nationally was only 7 percent. In other words, there’s a lot of potential for change — and, for now, New York City appears to be leading the way.