On the day he would become homeless, Wesley Bryant was awoken by his wife, Alexis.

“Get up,” she told him. “There’s a flood outside.”

It was 8 a.m. on a Thursday in late July, two years ago in rural Pike County, Kentucky, and rain had been pouring for days. Overnight, it got heavier. Homes and vehicles were being swept down the narrow valleys of Eastern Kentucky’s mountainous terrain.

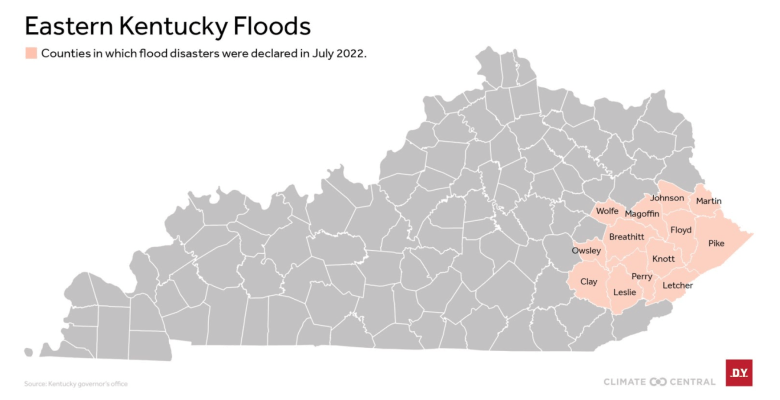

Dozens of people died after more than a foot of rain fell from July 26 through July 30, 2022, flooding 13 rural counties in Eastern Kentucky. Yet as these communities attempt to rebuild, they’re being overlooked for federal spending that’s protecting wealthier and more urbanized Americans from such weather disasters.

Wesley, Alexis, their two daughters and Alexis’ sister evacuated, hiking the half-mile to Alexis’ mother’s house via the mountains behind their own home to avoid flooded roads. They’ve been living there ever since.

Kentucky is a regular victim of flooding. During the past century, more than 100 people have died in storms across the state, including at least 44 two summers ago. Heat-trapping pollution is driving up rainfall rates and flood risks.

Thousands of survivors were forced to move out of damaged homes, including Wesley and his family. Their house, which Wesley’s grandfather built in the 1970s, is unlivable. Insulation peels from the ceiling and the floors bubble with water damage. Finding contractors to fix the house has been difficult because thousands of other flooded properties are also being repaired or replaced.

Their furniture and appliances were destroyed, and Wesley estimates replacing them would cost around $20,000. The family was denied FEMA disaster assistance so they’ve had to foot these costs themselves. “We just need a little help from our government,” he said.

Despite histories of flooding, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) classifies Pike County and the 12 other counties that flooded two years ago as facing “low” risks in the event of a natural disaster like a flood. That’s largely because they have less to lose —financially — compared to more urbanized areas.

Critics of FEMA’s risk-determination tool, called the National Risk Index, say it doesn’t include enough information about rural communities, especially when it comes to flooding, leading it to understate hazards.

That suggests that as the federal government cranks up spending on infrastructure, including the allocation of more than $1 billion to help reduce future flood threats, families in East Kentucky and other rural regions are at risk of missing out on projects that could help them prepare better for the next disaster.

Flood damage inside Wesley Bryant’s home. Courtesy of Wesley Bryant

What is the National Risk Index?

FEMA developed its National Risk Index to help local and state officials and residents plan for emergencies through an online tool. The agency sourced historic rainfall and other data to characterize these risks, allowing it to paint a national picture of threats from local disasters, findings that influence its spending decisions.

FEMA began developing the risk index in 2016, though initial work dates to 2008. The first iteration of the risk index was released in October 2020, and the data has been updated twice since then, most recently in March 2023.

Work to update how the risk index handles inland flooding is expected early next year. In a press release touting new requirements that forced the coming update, the Biden administration said that in “recent years, communities have seen repeated flooding that threatens both lives and property” but that the agency’s approaches to measuring risks based on historical data “have become outdated.”

The agency is also working on a “climate-informed” risk index looking at future hazards but, so far, inland flooding is not on the list of disasters planned to be included.

FEMA’s national and regional press offices declined to be interviewed or answer questions for this story.

“There’s a bias against, I think, rural communities, especially in the flood dataset,” said Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, a nonprofit that certifies floodplain managers and educates policymakers about flood loss. He said this bias could profoundly confuse or affect emergency managers in those areas.

“It’s giving false results,” Berginnis said. “I think we’ve got to be very thoughtful and very careful on how we use [the risk index] for the hazard of flood in particular.”

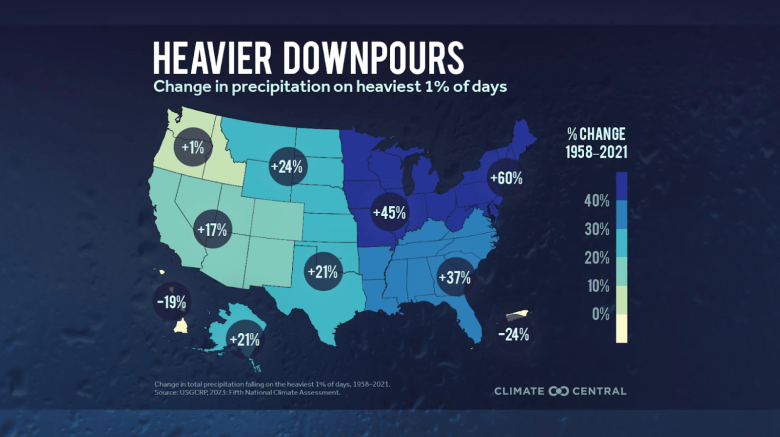

The building of homes and communities in vulnerable locations and the effects of heat-trapping pollution are converging to escalate the frequency of weather disasters across the U.S. One of the effects of climate change is an intensification in the amount of rainfall that can fall every hour. A federal report on the latest climate science showed the rainiest days across the Southeast are dumping more than a third more water on average now than was the case in the late 1950s. Ongoing emissions and warming threaten to continue to boost rainfall rates.

“If it’s gone up that much already, we might be wise to be concerned,” said Scott Denning, an atmospheric sciences professor at Colorado State University who studies carbon dioxide, water, and energy cycles. “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

That rain often falls on ground where coal mining excavations removed mountaintops. Researchers overlaid data regarding fatalities from the floods with maps of mountaintop removal mining and found that many of the deaths were downstream from or adjacent to such sites.

Neglecting rural Americans

Todd DePriest doesn’t “believe in Facebook,” but uses his mother’s account to surf the website’s digital marketplace. That’s what he was doing two summers ago when he saw alerts about severe floods in Letcher County, Kentucky, where he serves as the mayor of Jenkins, population 1,800.

Public service announcements warning people to “turn around, don’t drown” during floods were circulating on his mother’s feed. DePriest got up from his computer to look out the window at the torrential rain and realized the threat his own town was about to face.

DePriest jumped in his Jeep to check on the bridge at the lower end of Jenkins. When he got there, the road across the bridge had already flooded.

“I started calling people I knew down there and said, ‘Hey, the water’s up and if you want to get out of here, we’re going to have to do something pretty quick,’” DePriest said.

His next calls were to the fire department to prepare them for the emergencies to which they were likely to respond, then to city workers to get essential maintenance vehicles like garbage trucks to higher ground.

Letcher County was one of the hardest hit of the 13 counties declared federal disaster areas by FEMA. Five of those killed across the region were in Letcher County.

Two years since the floods, the region is still rebuilding. “They (FEMA) were telling us it was going to take four or five, six years to recover and get through this,” DePriest said. “And I thought, well, there’s no way it’s going to take that long.”

Now, DePriest hopes it only takes five years.

“All the processes and dealing with FEMA – and I think they’re fair in what they do – but it’s just a process,” DePriest said.

The National Risk Index multiplies a community’s expected annual loss in dollars by their risk factor. Like most of the east Kentucky counties that flooded two summers ago, Letcher County’s risk level is scored “very low” by the risk index.

That’s because it includes annual asset loss in its equations.

Rural counties like Letcher, where the average home costs about $75,000 and median household income is half the national average, score lower on the risk scale because there are fewer dollars to lose when disaster strikes. The area’s flood hazard threat is deemed relatively high but the potential consequences in financial losses are lower compared with denser areas.

The urban-rural disparity can be examined by comparing how the National Risk Index judges Jackson, Kentucky, a small city about 80 miles southeast of Lexington, with Jackson, Mississippi, the Magnolia State’s populous capital.

Both cities saw disastrous flooding during the summer of 2022. Unlike its namesake in Kentucky, Jackson, Mississippians suffered no flood deaths, though financial damage was far worse — an estimated $1 billion.

Hinds County – home to Mississippi’s capital – is assigned a “relatively moderate” risk level. Its social vulnerability is categorized as very high, with community resiliency categorized as relatively high, meaning the community is expected to bounce back more effortlessly after disaster. River flooding is deemed the second greatest natural disaster risk, with annual losses estimated at about $15 million.

To compare, Breathitt County, where Jackson, Kentucky, is located, is given a “very low” risk level by the National Risk Index. Its social vulnerability is categorized as relatively high and community resiliency is categorized as very low, suggesting it would need more help after disasters. Although FEMA considers river flooding the greatest disaster risk to the community, its annual losses are rated at just $1.3 million.

This urban-rural difference matters because FEMA uses the National Risk Index to determine how much money communities should receive to better prepare for natural disasters. For example, it’s being used to make decisions about spending $1.2 trillion available to lessen future flood risks under the U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The risk index is also used to determine which communities get money through FEMA’s Community Disaster Resilience Zones program, which designated 483 community census tracts as Community Disaster Resilience Zones last year. This means the communities inside those tracts can receive extra money for disaster planning. Of those census tracts, a third are federally classified as rural.

Disaster experts say relying solely on the risk index can disadvantage places that lack long-term weather records — which are often missing from rural communities.

Weather stations can be sparse in treacherous landscapes. Rural areas are among the last to have their flood hazards mapped by FEMA, with the agency prioritizing higher-density regions. And National Weather Service offices tend to be located in more urban areas, according to Melanie Gall, co-director of the Center for Emergency Management Homeland Security at Arizona State University.

“I think that we miss a lot,” she said.

Progress post-flood

Immediately after the July 2022 floods, FEMA and Kentucky Emergency Management began temporarily providing trailers for hundreds of flood survivors. Both programs have since ended.

FEMA gave trailer occupants the option to purchase their units as permanent housing. The trailer cost was determined by a formula that factored the type of unit, its size, and how many months it had been occupied by the interested buyer.

In the middle of the most recent winter, 18 months after torrential rainfall on steep slopes left so many families homeless, federal trailers that hadn’t been paid for were hauled away.

Kentucky’s program offered more flexibility: While the program has ended, three families still live in state-funded campers, according to Julia Stanganelli, flood recovery coordinator for the Housing Development Alliance. The Eastern Kentucky-based affordable housing developer has led the efforts to rehab and rebuild houses lost in the flood using state disaster money.

The three families are living in the campers while they wait for a new housing development to be built above the floodplain in Knott County, Kentucky, Stanganelli said.

East Kentucky’s population was declining long before the floods. Shaping Our Appalachian Region, a nonprofit focused on population retention and growth, estimates Eastern Kentucky has lost nearly 55,000 residents since 2000. The floods accelerated the losses.

During the 2022 floods, already sparse cell service went out entirely, and even the U.S. Weather Service’s on-duty warning meteorologist faced busy or disconnected phone lines, recalls Jane Marie Wix, a warning coordination meteorologist with the Weather Service.

Wix said the creek near her house turned into a “river,” preventing her from reaching work. “I don’t think I’ve ever felt so helpless before.”

Locals are working to better prepare for the next disaster, with or without federal government help.

Todd DePriest, the mayor of Jenkins, worked with the nonprofit law firm Appalachian Citizens Law Center to pay for four stream monitors that can trigger flood warnings.

Wesley Bryant, the Pike County resident whose home flooded two years ago, said he’s called his state representatives “hundreds of times” to keep Eastern Kentucky’s disaster recovery top of mind.

Bryant said he recently felt “pretty defeated” after receiving another notification about failing to qualify for federal assistance. But he said he won’t quit fighting.

“This is my home, this is my commonwealth,” Wesley said. “I’m going to fight for it.”

Update:

Following the publication of this story, a FEMA spokesperson reached out to clarify that responses to emailed questions initially provided “on background” were available for publication.

Those statements included that, of the NRI’s benefits, “[h]aving a baseline knowledge of natural hazard risk is essential for preparing for, recovering from, mitigating, and ultimately reducing the impacts of these hazards on an individual to nationwide scale.”

Rural communities face “unique challenges” for data collection around natural hazards, given that these weather events are more likely to be reported from urban areas and along roads, the spokesperson added, and rural areas often face a “more substantial challenge” in the “lack of capacity in terms of staffing, expertise, and resources to collect and store the data.”

FEMA’s spokesperson reiterated that the agency is consistently soliciting and receiving input from experts on natural hazard risk assessment, and working with states, tribes, and territories to fill in current data gaps and implement other feedback.