For the past three years, California has been suffering under the worst drought in state history. Key reservoirs have bottomed out, farmers have left their fields unplanted, and cities have forced residents to let their lawns go brown.

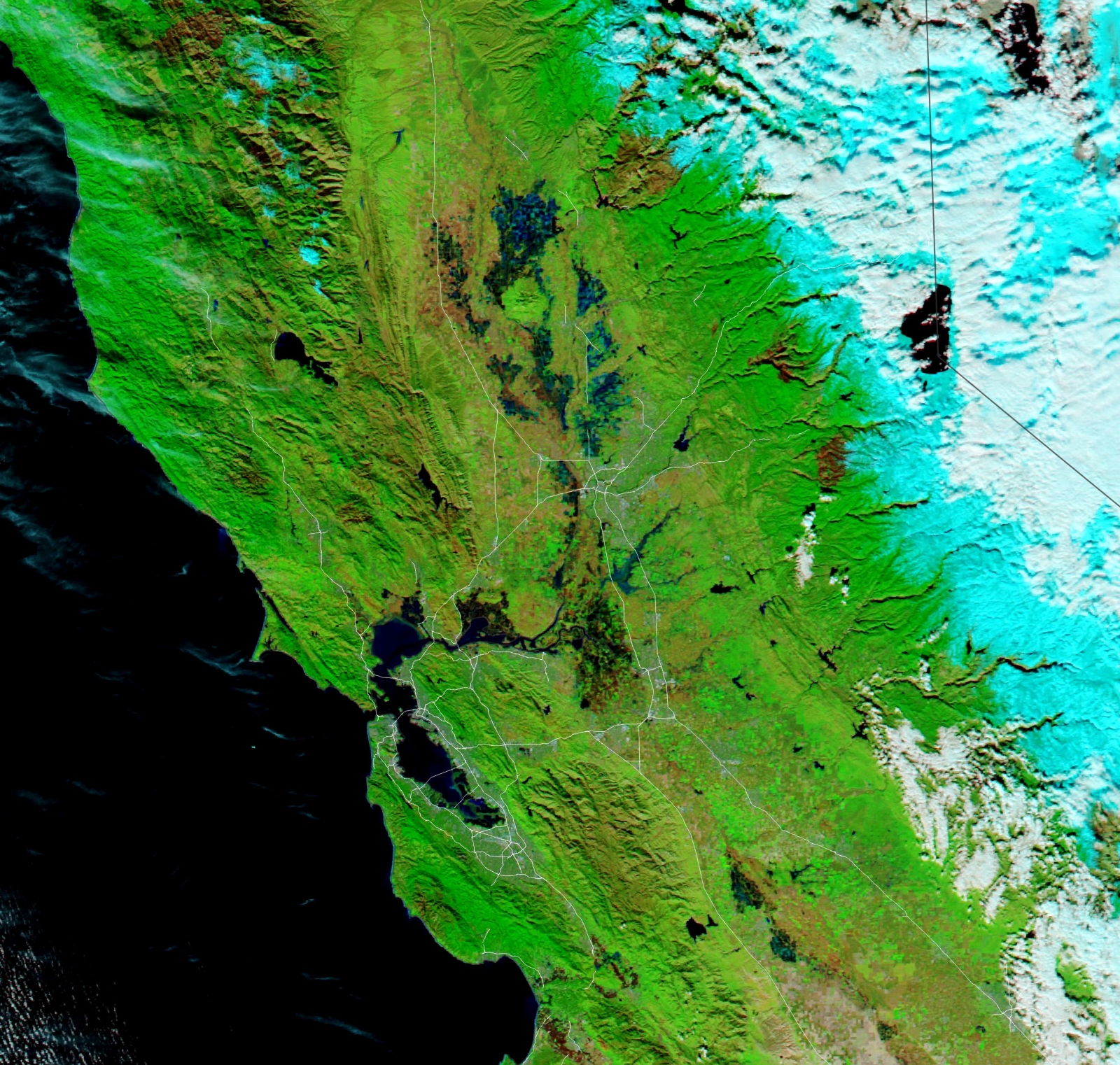

Now the state’s weather has taken a violent swing in the other direction. A series of powerful “atmospheric river” storms — so called because they look like horizontal streams of moisture flowing in from the Pacific — have brought record-breaking precipitation to the Golden State over the last two weeks, dropping almost a foot of rain in the San Francisco Bay Area, overwhelming the state’s rivers, and bringing several feet of snow to the Sierra Nevada mountain range in the eastern part of the state. The storms have caused widespread devastation, destroying critical roadways in the Bay Area and killing at least five people.

Though it has come at a tremendous cost, the past few weeks of rain have helped to refill the reservoirs that supply much of the state’s water, and snowpack levels in the Sierra Nevada are now well above their average levels for this time of year, meaning that major rivers will be much more robust after the snow melts in the spring. Barring a major dropoff, this year will be much wetter than the last few.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” said Jered Shipley, the general manager of the Anderson-Cottonwood Irrigation District, which provides water to pasture owners in the northern part of the state. “It gets us on track.” Shipley’s district takes water from Lake Shasta, the state’s largest reservoir, which all but bottomed out during the drought but has started to rebound over the past month.

If the reservoirs fill up as predicted, that will be great news for farmers and cities up and down the state, from Chico all the way to San Diego. Come spring and summer they’ll release the stored-up precipitation to cattle ranchers, nut farmers, and local water utilities around the state, ending a three-year spell of privation.

“To put it very bluntly, it’s been total devastation,” said Shipley. “This drought was a natural disaster. You may not have seen apartment buildings on fire or communities underwater, but [there were] displaced families, migrant workers not having jobs, businesses closing because nobody needed to service their tractors, feed stores closing.”

Even if 2023 does end up a wet year, it won’t prevent an ongoing water crisis, because surface precipitation is only one pillar supporting the state’s water needs. Since the reservoirs can’t hold more than a year of water, officials don’t have the option of holding it back to conserve for future years. And the other two pillars ensuring regular water availability in the Golden State — groundwater and the Colorado River — are facing crises that even a wet year won’t fix.

“This will fill our reservoirs, so that’s the good news,” said Jeffrey Mount, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California’s Water Policy Center, who studies atmospheric rivers and their impact on California’s water. “But we have been in a really dry period for the last 20 years, and that hasn’t come to an end yet.”

In the agriculture-heavy Central Valley, for instance, many farmers rely on water deliveries from a federal canal that funnels water westward from the Sierra Nevada. But households in this area also depend on groundwater withdrawn from underground aquifers, and recent research shows that these aquifers are drying up at an alarming rate. This dropoff has led to a surge in the number of dried-up wells in recent years and has forced some towns to rely on deliveries of bottled water.

A deluge of snow may help recharge the reservoirs that supply major Central Valley irrigators, but it won’t refill the underground aquifers in the region, in part because most valley communities don’t have the ability to store excess water. In other parts of the country like Arizona, officials can bank water from wet years in underground aquifers, but any extra rainfall in the Central Valley just gets lost.

Cities in the Los Angeles metropolitan area face a similar two-pronged challenge. The region gets about a third of its water from the State Water Project, a canal system that diverts water from the reservoirs in the northern part of the state, and these deliveries have declined in recent years, forcing some cities to make drastic cuts.

The current bout of rain will help fill up those reservoirs, but the rest of the water used by these cities comes from the Colorado River, which snakes through the arid western United States. The river’s two main reservoirs in Nevada and Arizona are both in danger of bottoming out this year, and the federal government may soon slash California’s water allotment to stop that from happening. The rainfall from this week’s atmospheric river event won’t do anything to alleviate that crisis, although it will make the most dire scenarios for Los Angeles much less likely.

“Our focus tends to be on filling of surface reservoirs, and everybody declares the drought over,” said Mount. “That’s just fundamentally wrong.”

Atmospheric river storms like the one that struck California this week account for as much as half of all West Coast precipitation even in normal years, which makes them critical for bringing the region out of prolonged drought periods. The most recent forecasts suggest that this year’s wetter trend will persist through the winter, but there’s still a small chance that “the door slams shut,” as Mount puts it, and rain stops altogether. The northern Sierras also saw high precipitation totals in November and December of 2021, but then the rain flatlined in January and February of last year, leaving the state well short of average rainfall.

“It doesn’t look like that right now,” Mount told Grist. “None of the models I’m aware of are saying that it’s going to stop.”