This story was produced in collaboration with High Country News, in partnership with California Health Report.

Lee este artículo en español aquí.

When I visited Christina Gonzalez and her family in April, she sat slumped in her family’s worn black faux-leather couch, trying to recall which explosion had shaken her neighborhood the most. The seven decades they’ve lived in Wilmington, California, are marked by the dates of the high-octane industrial fires that have erupted at each of the five refineries that surround their home.

There were so many disasters, she and her husband, Paul, both 73, told me. Was it the one in ’84? Or maybe the one in ’92 or ’96? Each fire painted the sky in different shades of black and orange. Paul believes the biggest one might have been later — closer to ’01, maybe, or even 2007 or 2009. He shifted uncomfortably in their living room; a recent procedure on his hip still made sitting difficult. “When that refinery blew, there were black dots everywhere,” Christina said, her short dark red hair framing her face, which was marked by lines from the stress. “All over the cars, the house, our fruit trees and patio furniture.”

“It was raining oil,” she said. She retired soon after that.

She had worked in the attendance office at Wilmington’s Banning High School. She remembered how often students came through, their faces flushed with sickness. “I’d see it in their notes,” she said. “Gone to the doctor, asthma, breathing issues, coughing — all the time. It was kind of heartbreaking to see these kids have to suffer as teenagers, and you could see it in their faces, how they didn’t feel well.” That was around the time her second-youngest grandchild was born.

Poor health, she says, is a painful but routine fact of life in her South Los Angeles community, an 8.5-square-mile tract surrounded by the largest concentration of oil refineries in California, as well as the third-largest oil field in the continental U.S., and the largest port in North America. A recent Grist investigation found that since 2020, Wilmington has experienced a dramatic rise in deaths related to Alzheimer’s, liver disease, heart disease, high blood pressure, strokes, and diabetes — all conditions known to be exacerbated by high levels of pollution.

Illness has spread through the Gonzalez home, too. Christina has been diagnosed with lung disease, lupus, and fibromyalgia, while her daughter, Jennifer Gomez, 42, has acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a cancer of the blood cells. Jennifer’s husband has had two heart attacks, and her teenage son has “been hospitalized more times than a 90-year-old” for multiple severe respiratory infections.

Eight members of the family reside in the house today. Paul’s mother, the first to move in, battled breast and skin cancer. Paul himself beat testicular cancer — twice. With his daughter’s diagnosis, that’s three generations of cancer in the same household. Since the early 1960s, the family has lived on Island Avenue, just one block from the Port of Los Angeles and about one mile from the Phillips 66 Los Angeles refinery. Jennifer jokes that a sane family would have moved, but the family knows it’s not that simple.

Jennifer Gomez, left, was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a cancer of the blood cells. Her great grandmother, Irene Gonzalez, left, is a 94-year-old leukemia and breast cancer survivor. Photos by Pablo Unzueta

Housing in Los Angeles is more expensive now than it has ever been. Besides, there aren’t many places in Southern California where industry’s grasp is any looser. Riverside, located in California’s Inland Empire, is a prime example. The city used to be one of the most popular locations for Black and Latino families locked out of housing in Los Angeles, but today it’s the site of a major warehousing boom and has the country’s highest concentration of diesel pollution. “We can’t afford to sell, because where could we afford to buy?” Paul said. “It used to be that you could afford to buy out towards Riverside, but now that’s getting to be more expensive than LA. There’s no escape route.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, says that air pollution can cause adverse health effects months or even years after initial exposure. “I know even if the pollution gets better and these refineries close, it is something that will stay within all of us for the rest of our lives,” Jennifer said.

Since 2000, more than 16 million pounds of toxic chemicals, primarily hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide, have been spewed into Wilmington’s air from industrial sites in the city, according to the EPA. That amounts to more than 2,000 pounds of chemicals every single day. Two-thirds of the chemicals were emitted by the Phillips 66 refinery.

In response to an inquiry from High Country News and Grist, a representative from Phillips 66 sent an email statement, writing that its Los Angeles refineries are striving to improve operations in a “safe, reliable and environmentally responsible” way and noting that company has employed $450 million in “emissions-reduction technology” since the early 2000s. The EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory data does not include another major source of pollution in Wilmington: The twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are the largest in the nation as well as the single largest fixed source of air pollution in Southern California; collectively, they are responsible for more pollution than daily emissions from 6 million cars.

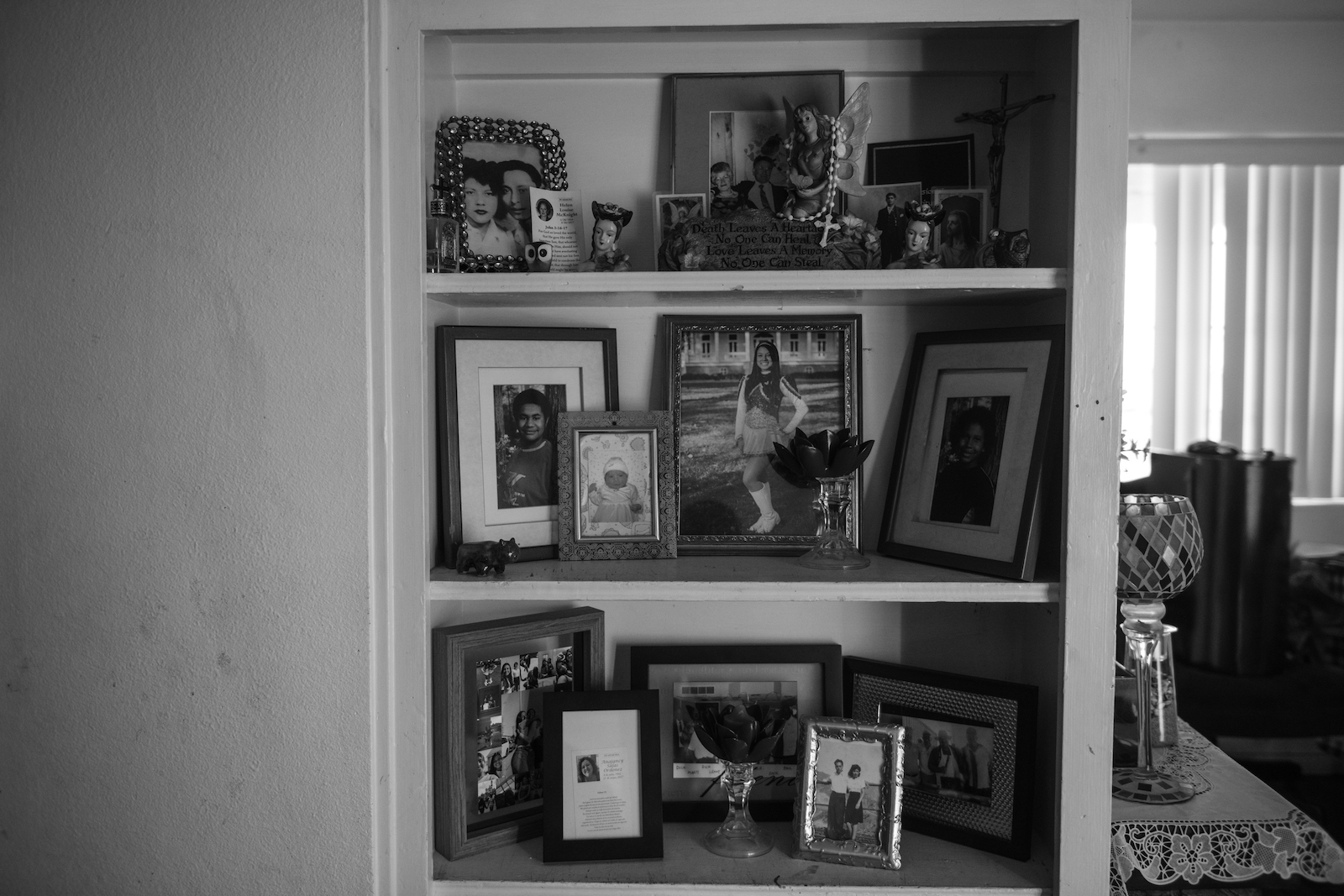

The walls of the Gonzalez home are decorated with family photos. When I visited Jennifer and Christina in April, Christina wore a shirt with the word “JOYFUL” written on it in five different colorful fonts. Our conversation was sobering, despite the presence of a six-foot-tall stuffed animal that the children adore. “You can’t go outside without hearing trucks from the port going down your street, seeing a cloud of smoke from one of the refineries filling the air, or tasting the sulfur,” Christina said. “I’ve gotten to the point where you could say I’m depressed.

“I get tired of calling the doctors to make appointments because I’m having breathing problems,” she added, “and then with the pandemic, being stuck inside watching my daughter (Jennifer) get so severely sick with leukemia.”

Just a few weeks after we spoke, Christina was hospitalized for a serious infection. She spent two weeks in the hospital and was then released for daily treatment at home.

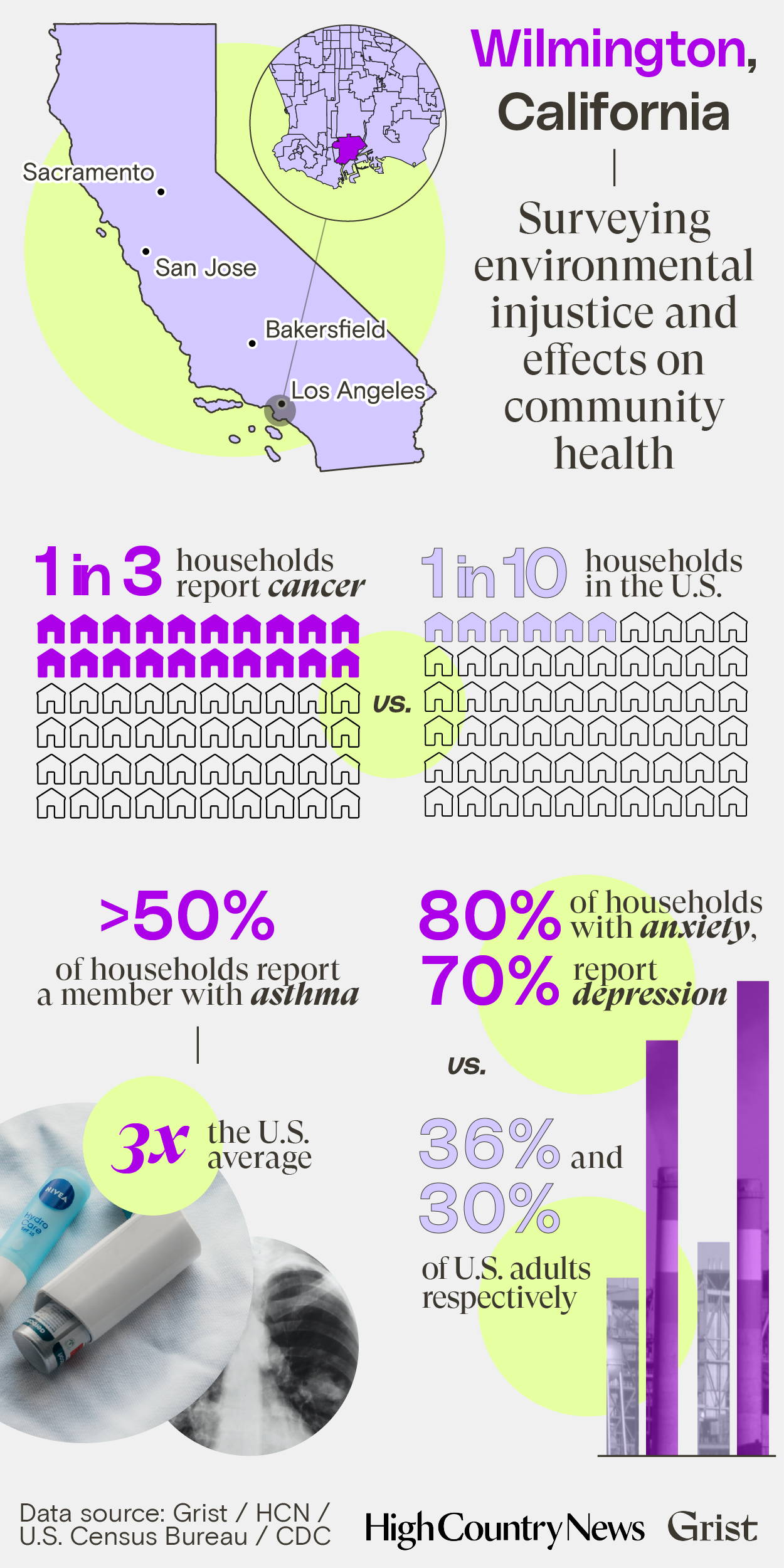

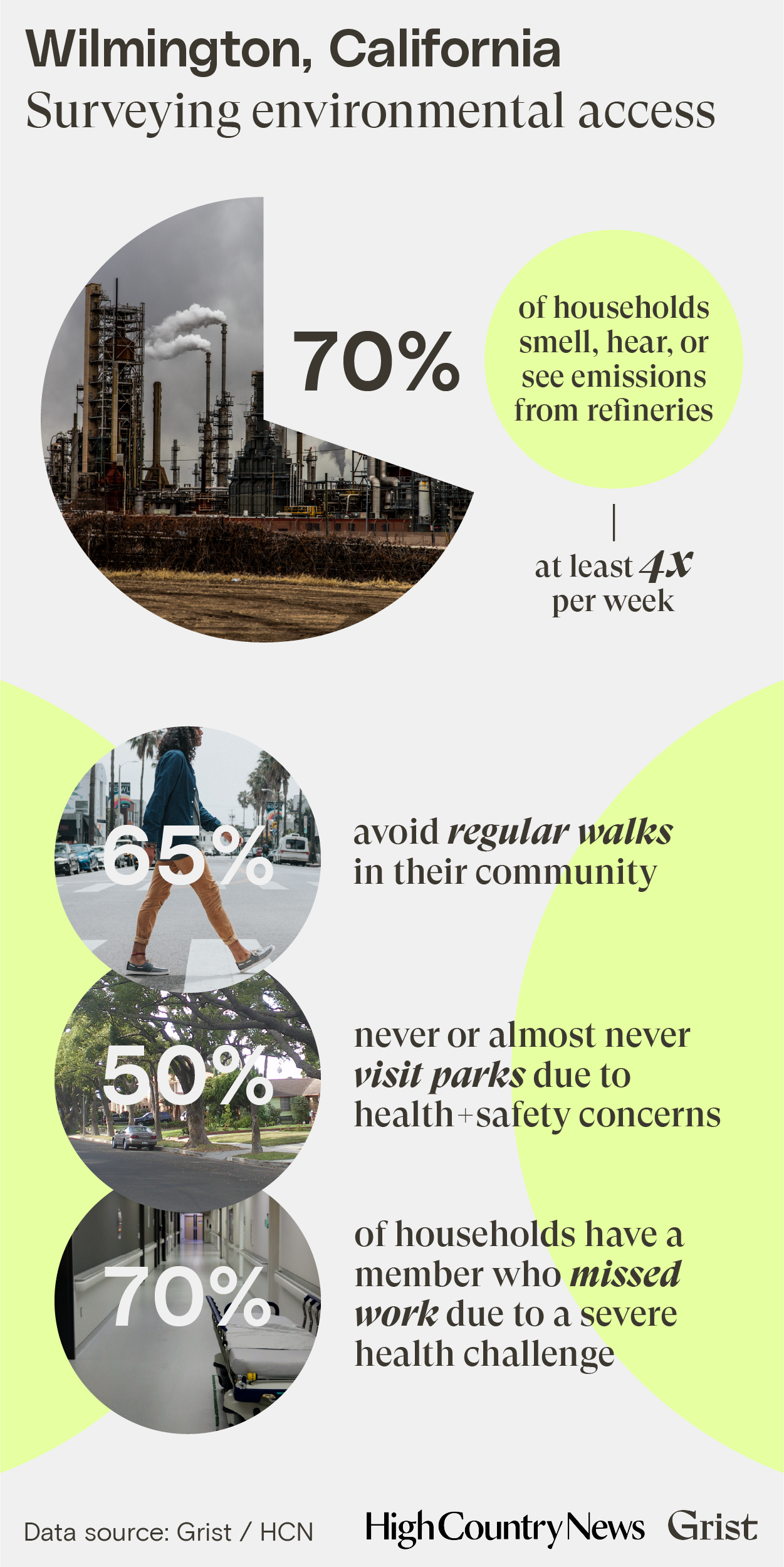

This year, I moved back to Wilmington, where I grew up, after five years away. In part, my return was driven by a desire to write about — and on behalf of — my old hometown, an assignment that started with uncovering the hidden impacts of a century of environmental injustice. For three months, I canvassed the 1.5 square-mile area around the 103-year-old Phillips 66 refinery, an area that included my childhood home. My project, supported by Grist and the University of Southern California as well as by High Country News, focused on the physical, environmental and mental health impacts of air pollution. It came down to this: What is it like to live next to an oil refinery? Roughly 2,200 homes were initially contacted through in-person canvassing and postcards. Ultimately, 75 households, home to more than 300 people, opted to participate. The collected survey data has a 10 percent margin of error, equivalent to that found in the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Here is what we found:

While I found the survey responses to be shocking, Alicia Rivera, a community organizer in Wilmington, reacted stoically when I shared the data with her. “None of this is unexpected,” said Rivera, who organizes with the Wilmington-based environmental justice organization Communities for a Better Environment. “In fact, it corroborates and legitimizes what we see every day, and it brings into question the ‘official’ data and stories we’re told from regulators.”

For more than a decade, Rivera has been an integral part of Wilmington’s community-organizing ecosystem, seeking accountability from both industry and regulators. Most recently, she was a lead organizer for a successful drive to phase out oil drilling in the city of Los Angeles. But it will take more than a few legislative changes to bring justice to the residents, she said.

“We struggle, and we struggle,” she told me, sitting in her organization’s office a few blocks from the port. “No one seems to understand how much frontline communities have put on the line — our health and lives — just for these polluting companies to profit.”

California is often held up as a model for climate policy, environmental legislation, and pollution regulation, but those standards are rarely reflected in frontline communities, said Hillary Angelo, a sociologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Angelo, who recently published a study analyzing climate plans in 170 California cities, found that local governments aren’t adequately implementing structural changes now.

“Communities on the front lines dealing with legacies of pollution, bad planning, and exclusionary practices are already confronting climate impacts directly,” she said during an interview earlier this year. Her research showed that local governments were more inclined to pass legislation with an obvious aesthetic appeal, such as tree-planting initiatives, rather than initiatives that took “histories of racial and economic injustice” into account.

“The inclusion of ‘green’ policies doesn’t seem to have any relationship to the needs in particular places,” she explained. In a place like Wilmington, it is “much harder to pass the important life-saving policies like improving public transit and affordable housing or funding contamination cleanup and renewable energy.”

Few of the Wilmington residents Rivera works with initially make the connection between the climate crisis and the issues plaguing their community. Once they do, however, it is an eye-opening experience. “Their biggest concern initially is the pollution from refineries, because it’s the more visible thing,” she said. “Then they realize its impact on their quality of life, their crumbling streets, the smells in the air. They start to put things together about how it is associated with their poor health.”

Our survey found that Wilmington’s industrial makeup hampers access to the outdoors:

Over the last four years, Rivera and other local organizers have created the Just Transition Fund to ease the impacts of life in an industrialized community. From President Joe Biden’s proposed Civilian Climate Corps to California’s Climate Jobs Plan, various attempts have been made to fund and otherwise support the nation’s shift to clean energy, but the programs tend to neglect the cumulative impacts of the country’s historical dependence on fossil fuels. The Just Transition Fund, Rivera said, would not only help fund training programs for clean energy workers and environmental remediators, it would also pump cash directly into frontline communities like Wilmington.

“We need accountability,” Rivera said, “and one way to do that is by using federal funds and corporate funds to help pay for things like health care and disability coverage in places paying the price for our pollution.”

Jennifer Gomez acknowledges that programs like Rivera’s would have an immediate positive effect on Wilmington. At the same time, however, they won’t erase the past, and they certainly won’t cure those already suffering from cancer in the community.

“I told my oncologist that if I survive, I want to fight back against the refineries and pollution,” Gomez wrote in her response to our survey earlier this year. “I firmly believe it’s why I got cancer, and why my best friend died of cancer, too, as well as so many other Wilmington residents.”

Adam Mahoney is an environmental justice reporter at Capital B, a local-national nonprofit publication focused on the Black experience. He is based in Wilmington, California.

Yoshira Ornelas Van Horne, an incoming assistant professor at Columbia University’s School of Public Health, served as a research advisor to the survey project. Pablo Unzueta and Grace Mahoney contributed additional reporting to this story.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Data Fellowship.