As a child, Preston J. Arrow-weed lived near a stretch of the Colorado River that traced a wide, sweeping curve through the Fort Yuma-Quechan Reservation, which straddles the border of California and Arizona. The tribal elder recalls the way the river would swell during certain seasons, as rain or runoff upriver would send sediment-laden water coursing through the channel.

“The water was so swift, and when it first came it would be sandy and brown, then after it settled it became blue,” said Arrow-weed, 81, a singer, actor, and playwright who is a member of the Quechan Indian Tribe. “We used to get a bucket of water from the river and take it home. Then, when it settled, we’d drink it.”

Nowadays, the once-wild river flows mechanically into a concrete canal that diverts most of the streamflow toward distant lettuce fields in California’s Imperial Valley before it reaches the reservation. Flowing downstream from the reservation, the river usually dries up before it crosses the U.S.-Mexico border, 15 miles south of Yuma, Arizona.

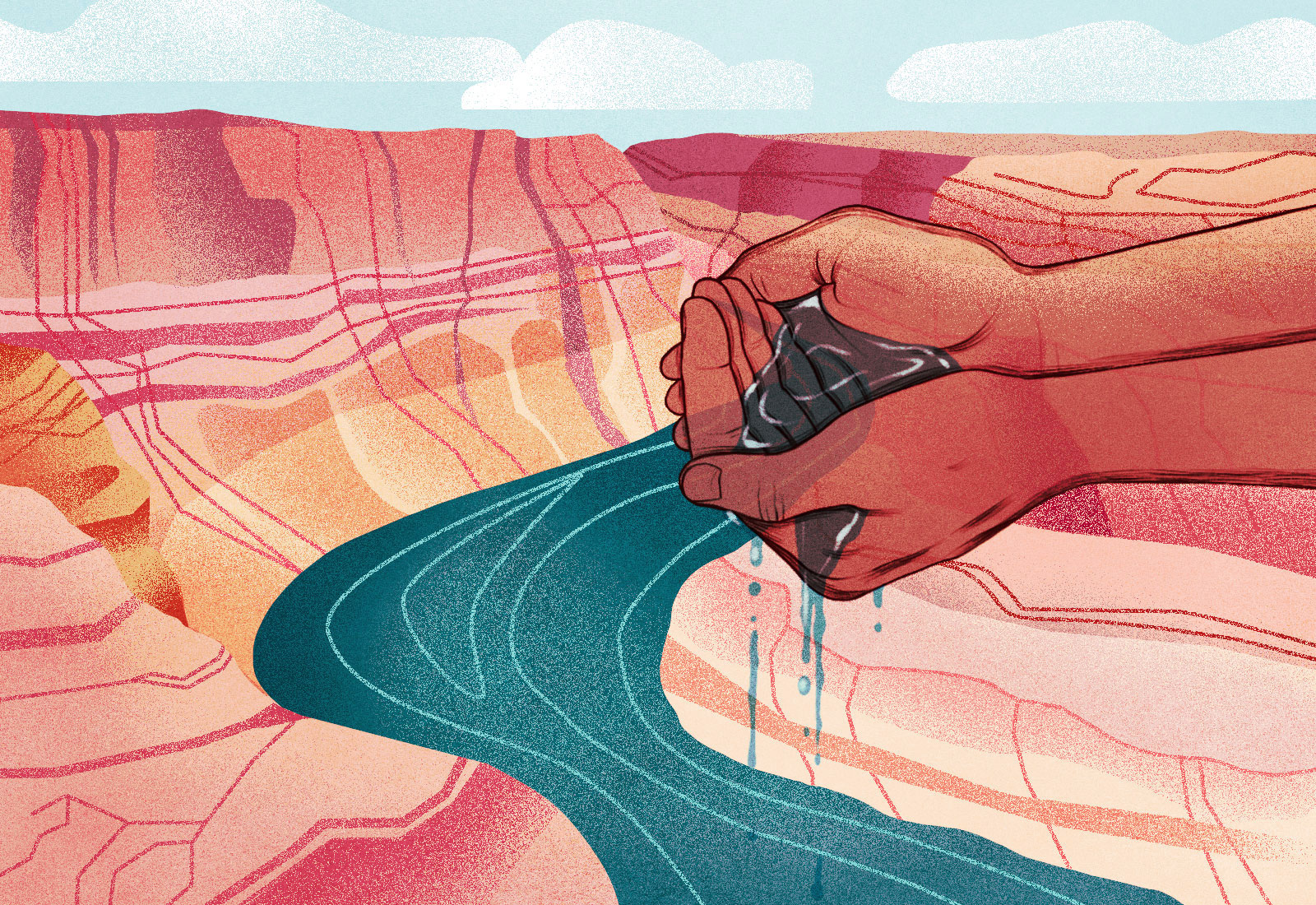

The changes Arrow-weed has witnessed during his eight decades on the river may have seemed gradual, but now, after years of decline, the once-mighty waterway is a sliver of its former self.

“It’s about 20 feet wide at the most,” he said. “You can walk across it.”

The Colorado River Basin encompasses seven U.S. states and supplies water to 40 million people. Over the past two decades, the basin has experienced record-setting heat and some of the driest years ever recorded, which have combined to sap the river of water at unprecedented rates. The largest reservoirs on the river have dropped to alarmingly low levels in recent months, forcing Western water managers to rethink how they operate in the face of scarcity.

Last month, federal officials sounded the alarm by declaring the first-ever water shortage in the basin. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation cited “historic drought,” climate change, and low levels of runoff from the Rocky Mountains as reasons for the continued decline of Lake Mead, the massive reservoir near Las Vegas held back by the Hoover Dam. Lake Mead’s stores are used by millions of people in the lower half of the basin, while serving as a critical safeguard against drought-related shortages.

Lake Mead is considered full when its stores reach 1,220 feet above sea level or more, but the reservoir is projected to sink to 1,066 feet above sea level by the end of the year, revealing rock that has been submerged since it began filling in the 1930s. With every foot that Lake Mead falls, the basin comes closer to triggering substantial cutbacks for certain water users along the river. The first round of reductions, which will take effect next year, will primarily impact farmers in central Arizona. But if lake levels continue to decline, future cutbacks could impact the 30 Native American tribes with lands in the basin.

Indigenous nations have recognized rights to more than one-fifth of the basin’s annual supply — more than a trillion gallons, or nearly enough to cover an area the size of Connecticut in a foot of water. That allocation is likely to increase in the future, because 12 of the tribes in the Colorado River Basin are still engaged in the decades-long process of resolving their water rights claims, according to the Water & Tribes Initiative, a coalition of tribal representatives, water rights attorneys and academics.

Tribal water rights differ from state-based rights in several ways. Unlike a state or irrigation district, a tribe’s right to water dates back at least as early as the creation of its reservation. Despite having federally reserved water rights, tribal claims were largely ignored until the 1960s, when the U.S. Supreme Court adopted standards allowing tribes to have their rights quantified, a form of legal recognition that identifies the amount of water to which users hold rights.

But even for tribes that have resolved their rights, some face significant barriers to fully using their water, including a lack of necessary infrastructure, funding challenges, and limited legal options to put their water to use outside their reservations through leases or other arrangements.

If a tribe does not (or cannot) use all the water it is entitled to, it doesn’t go unused; thirsty cities and agricultural fields downstream from reservations siphon off the surplus, but with no compensation for the tribe.

“The basin is free-riding off of undeveloped tribal water rights,” said Jay Weiner, an attorney for the Quechan Indian Tribe. Weiner said there is a “fundamental tension” between tribes’ desire to fully develop their water rights and the overarching need for everyone in the basin to consume less water overall.

Tribes with substantial diversion rights may remain unscathed by the initial reductions, with some even in the position to contribute water back into the system. But other tribes are less fortunate; in addition to unrecognized water rights, deteriorating infrastructure, and water insecurity issues, some tribes could face cutbacks to their water supply as early as 2023.

Whether a tribe is flush with mainstream flows or struggling to access clean drinking water, every tribe in the basin must navigate the complicated legal landscape that governs water rights on the Colorado.

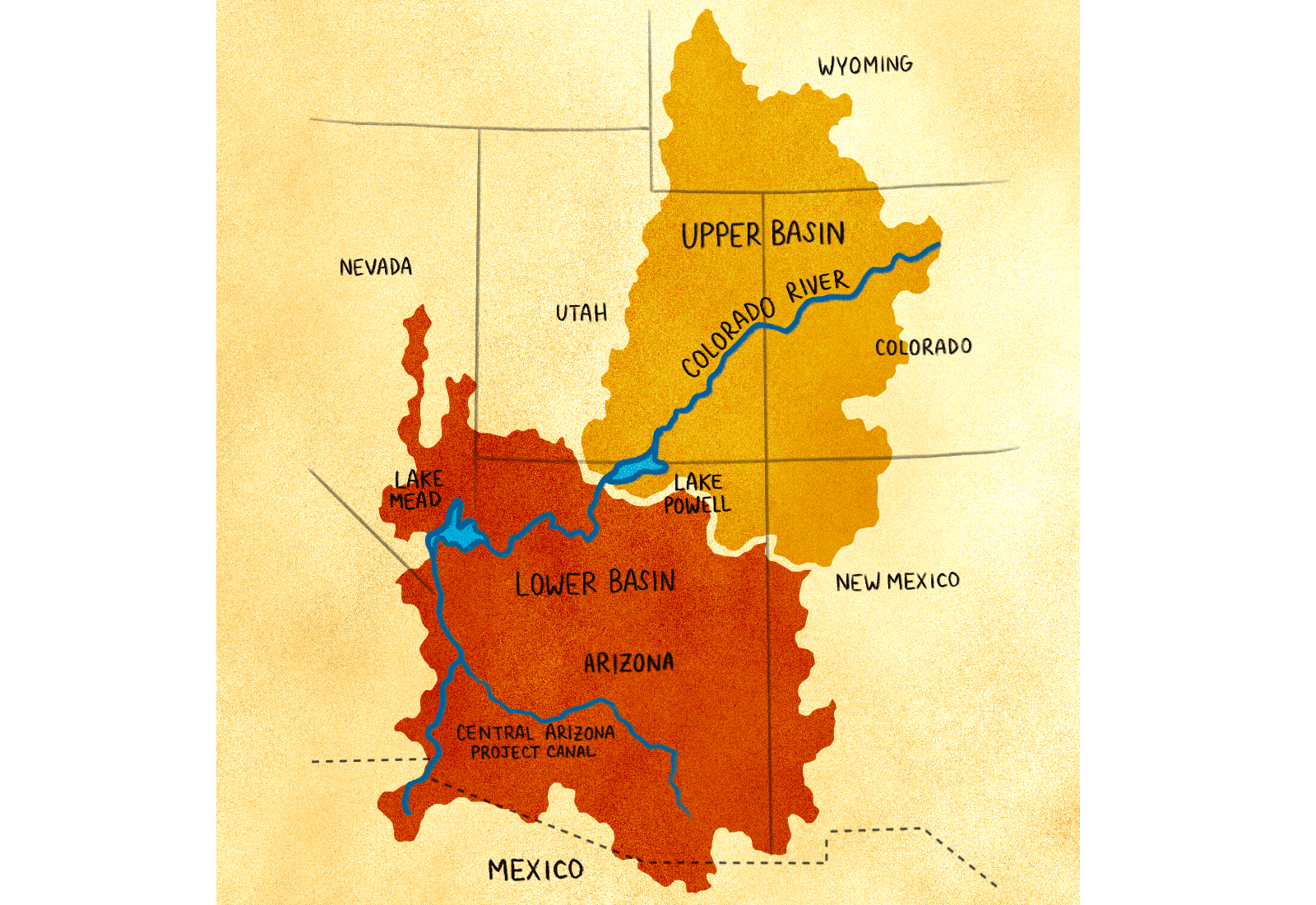

Much of the water that flows through the Colorado River starts as snowpack in the southern Rockies. The snowmelt produced in spring then flows into tributaries in states like Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado. These states are part of the Upper Colorado River Basin: The lands fed by waters of the Colorado River system were divided into an upper basin and a lower basin during the negotiations for the 1922 Colorado River Compact. The so-called “law of the river” is an amalgamation of interstate compacts, statutes, regulations, court decisions, an international treaty, and the seminal 1964 U.S. Supreme Court decree in Arizona v. California, which enabled several tribes to quantify their rights.

In Utah, one of those tributaries — the Green River — flows through the lands of the Ute Indian Tribe, which had a portion of its water rights quantified in the 1920s but is still litigating unresolved claims. Because the Ute tribe has not fully resolved nor developed those rights, much of the tribe’s water goes unused and flows toward Lake Powell, the second-largest reservoir on the Colorado River.

Despite the declining water levels at the lake, the state of Utah is forging ahead with a proposed $2 billion pipeline that would pump water from Lake Powell to largely non-Native communities near St. George — 140 miles away, in southwestern Utah. Critics blasted the proposal, citing the state’s failure to recognize the tribe’s water entitlements, its refusal to conduct meaningful tribal consultation and, more generally, its antiquated approach to water development in the Western U.S.

The Ute Indian Tribe has a pending lawsuit challenging the project, arguing that the pipeline would obstruct the tribe’s efforts to fully develop its water rights. (The Ute Indian Tribe declined a request to be interviewed for this article, citing the ongoing litigation.)

“For over a century, the State of Utah has pursued a deliberate policy of interfering with and preventing the Ute Indian Tribe from exercising its federal Indian reserved water rights,” wrote members of the Ute Indian Tribe Business Committee in a statement released in July. “The Lake Powell Pipeline is another chapter in this saga.”

Battling for water rights is more than just a struggle for adequate water resources; it’s a fight for better health.

Tribes with unresolved water rights must undertake a convoluted settlement process to have their share of the river quantified. And while every tribe is legally entitled to enough water to satisfy their on-reservation needs, having unquantified rights poses additional challenges for those tribes, according to Bidtah Becker, an associate attorney with the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority.

The Navajo Nation has extensive water rights in both the upper and lower basins, but the tribe’s claims in the state of Arizona remain unquantified. Proposed settlements negotiated by the tribe a decade ago never materialized. In the coming years, court proceedings are scheduled to resolve the water rights of the Navajo, as well as the neighboring Hopi Tribe.

Becker said tribes without recognized water rights often face challenges in securing funding for water infrastructure projects, especially in areas where substantial water pipelines and other facilities would be required. The lack of adequate water infrastructure has long plagued the Navajo Nation, where residents are 67 times more likely than other Americans to live without access to running water.

Those inequities were further exposed when COVID-19 spread into the Navajo Nation, Becker said. A study published last year showed a strong association between COVID-19 infection rates and the lack of indoor plumbing.

As tribes with unresolved rights fight to settle their claims, the basin-wide shortage is forcing all stakeholders on the river to find ways to conserve water. That scarcity is likely to make striking a deal even more challenging than it has been in the past.

“It makes a hard process harder,” said Pam Adams, Native American affairs program manager for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Basin region.

Adams is one of the chief liaisons between the tribes and Reclamation, an agency under the Department of the Interior. Acknowledging the persistent challenges faced by tribes seeking settlements in the past, Adams said resolving all outstanding tribal claims is a priority among the department’s leaders, including Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo. Clarifying the rights of each tribe also gives greater certainty to other stakeholders in the basin, Adams said, adding, “It’s best for everyone to get them settled and this administration is certainly very supportive of that.”

The Bureau of Reclamation is currently building a 300-mile-long pipeline that will supply water from the San Juan River to portions of the Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache Nation. Becker said projects like the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project are significant steps, but that more needs to be done to address the lack of water security in Native American communities.

In a broad desert valley 150 miles east of the mainstem Colorado, irrigated rows of cotton and alfalfa line the sandy banks of Arizona’s Gila River.

Members of the Gila River Indian Community, or GRIC, irrigate thousands of acres south of Phoenix. With a population of more than 13,000 living on the reservation, the tribe traces its roots to ancient cultures that built expansive networks of irrigation canals to support large villages along the waterway. These days, the farmlands are fed by a new stream. The Central Arizona Project, or CAP, completed in the 1990s, is a 330-mile-long canal that conveys Colorado River water from Lake Havasu, on the California border, to central and southern Arizona.

The Gila River Indian Community, left, irrigated thousands of acres south of Phoenix, Arizona. Now, nearby lands are fed by the Central Arizona Project, right. Photos by Linda Davidson / The Washington Post via Getty Images, AP Photo / Ross D. Franklin.

Because the CAP has some of the lowest-priority rights on the river, the canal is subject to the first round of reductions next year. The basin-wide Drought Contingency Plan established a three-tiered system for imposing reductions in the lower basin based on the level of Lake Mead. Under a Tier 1 shortage (which is triggered when the elevation of Lake Mead falls below 1,075 feet), CAP water supplies will be cut by 30 percent — reductions that will primarily impact farmers in places like Pinal County.

The five tribes that draw from the CAP have some of the highest-priority rights on the canal, which largely buffers them from the initial round of cutbacks. If Lake Mead were to fall below 1,025 feet in elevation, the lower basin would enter a Tier 3 shortage, at which point Arizona’s diversion rights would be reduced by roughly 45 percent compared to the canal’s current supply.

“If we get to Tier 3, all the tribes that rely on CAP water have the risk of a reduction,” said Chuck Cullom, Colorado River programs manager for the CAP.

Even if continued declines were to trigger a Tier 3 shortage — the direst scenario envisioned in the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan — water deliveries to the Gila River Indian Community would be largely the same, according to Jason Hauter, a tribal member who represents the GRIC as an attorney.

“There would be cuts, but in terms of the community’s on-reservation use, they’d have water available to them under a Tier 3 shortage scenario,” Hauter said.

But a Tier 3 shortage is far from the worst-case scenario, because declining streamflows could push the level of Lake Mead below the 1,025-foot mark — a situation left unaddressed by the Drought Contingency Plan. While the chances of Lake Mead reaching critically low levels seemed remote when planning efforts began, projections released by Reclamation last month indicate there is a 66 percent chance the reservoir falls below 1,025 feet by 2025.

Falling below that level would trigger additional cutbacks, which would likely include curtailing tribal water deliveries from the CAP. And, because tribes on the CAP are allowed to lease their water rights directly to municipalities, future reductions to tribal water could also impact the water-supply holdings of cities and towns throughout central Arizona.

If Lake Mead were to fall below 900 feet, it would elicit the disaster scenario known as “dead pool,” in which water would no longer flow through Hoover Dam, cutting off the lower basin and shutting down a hydroelectric plant that provides electricity for millions of people in the Southwest.

Stephen Roe Lewis, governor of the Gila River Indian Community, said via email that the tribe is committed to working with other stakeholders in the basin to avoid that fate.

But, as hydrological conditions in the basin continue to worsen, deeper cuts seem inevitable. Reclamation’s Phoenix Area Office manager Leslie Meyers said next year’s reductions will have a minimal impact on tribal water supplies, but warned, “That won’t be the case in the future if we continue down this path.”

For thousands of years before the first concrete dams were built on the Colorado, the Mojave people — or AhaMacav, which means “people of the river” — maintained large settlements on either side of the surging stream. In 1865, the U.S. government lumped members of the Mojave and Chemehuevi tribes together to form the Colorado River Indian Tribes, or CRIT, which later came to include Navajo and Hopi families.

The CRIT’s water rights were quantified as part of Arizona v. California, the series of U.S. Supreme Court cases beginning in the 1930s that dealt with water disputes between the two states. Along with confirming the rights of the five mainstream tribes in the lower basin, the case also established the standard of determining tribal entitlements based on a tribe’s “practicably irrigable acreage.”

The tribe’s history of agriculture, including an 80,000-acre irrigation project built by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, enabled the CRIT to secure annual diversion rights of more than 700,000 acre-feet, the largest entitlement of any tribe in the basin. Although the CRIT uses a large portion of its water for farming and agriculture, much of its entitlements in both Arizona and California go unused — a fortunate fact for farmers in central Arizona.

The tribe has employed a number of creative approaches to generate revenue using its reserved water rights, including discontinuing certain existing water uses on tribal land, and using the water that is conserved to prop up levels in Lake Mead.

Water flows through infrastructure at CRIT Farms, located near Parker, Arizona, in the lower basin of the Colorado River. Images courtesy of CRIT Farms.

The tribe has agreed to fallow a portion of its historically irrigated farmland over the next three years, conserving a total of 150,000 acre-feet of water that will be left in Lake Mead. For its help in minimizing cutbacks for lower-priority users — such as agriculture served by the CAP — the tribe is receiving $38 million, mostly from the state of Arizona.

Margaret Vick, an attorney for the CRIT, said that although the tribe is well-positioned to contribute conservation water, its ability to benefit from other types of off-reservation uses are limited. Unlike tribes with water settlements, she said, the CRIT’s decreed water rights generally prohibit the tribe from directly leasing its water to off-reservation users. The tribe proposed federal legislation last year that would allow it to market some of its Arizona allocation, but the bill hasn’t been introduced in Congress, Vick said.

Although the CRIT’s water rights are quantified and it has enough water to contribute to Mead, the tribe has historically suffered from a lack of funding for necessary infrastructure — something that is often negotiated as part of a water settlement, Vick said. According to the Tribal Water Study, parts of the federal irrigation project were built in the late 1800s, and suffer from “design limitations and simple aging problems,” such as unlined canals and deteriorating gates.

Weiner, the attorney for the Quechan tribe, said that while each tribe is in a different situation, they generally agree on the need for more flexibility in the legal framework that governs the river.

“Tribes can coalesce around the importance of flexible tools and finding ways to allow tribes to benefit from their water resources,” Weiner said. “On-reservation development is certainly one of those ways, but things like off-reservation transfers and system conservation programs are other ways that tribes could potentially benefit from their water resources without necessarily having to add new consumptive demands to the system.”

Despite the challenges facing tribes in the basin, tribal leaders and water managers see opportunities for solutions that would help alleviate some of the water-supply pressures on non-Native stakeholders while enabling the tribes to benefit from their water. And, regardless of the water management decisions that are made going forward, the tribes want a seat at the table.

Tribal leaders often lament the lack of tribal consultation that occurs when federal or state governments make decisions that impact tribal resources. Secretary Haaland has emphasized the importance of tribal engagement during her time leading the Interior Department, but the level of tribal involvement in the basin’s next round of drought planning remains to be seen.

Noting the importance of cooperation between basin stakeholders, Becker, the attorney for the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, said the ongoing shortage should also serve as a reminder that water is not simply a commodity, but a vital substance on which our survival depends.

“We’ve created these systems where people pay money and they get a service,” Becker said. “But maybe what Mother Nature is saying to us is that, when it comes to something like water, we need to shift our approach so that people understand exactly where their water is coming from, and understand their role in protecting the most precious resource we have.”