Environmental justice communities and advocates across California celebrated a major victory in August when state legislators passed a bill to ban new oil wells and phase out old ones within 3,200 feet of sensitive sites like homes, schools, and hospitals.

It was a win decades in the making. Activists had spent years fighting to protect communities from the toxic impacts of neighborhood oil drilling, which include higher risks of cancer, asthma, heart disease, preterm birth, and other reproductive issues. Democratic state Senator Monique Limón, who introduced the setbacks bill, known as SB 1137, called its passing, “a historic moment in California history.”

But last week, Big Oil struck back. The California Independent Petroleum Association, or CIPA, the trade group representing drillers in the state, announced it has gathered enough signatures to force a referendum onto the 2024 state ballot. If approved by voters, it would overturn the state legislature’s decision and dismantle the new setbacks law, leaving it to CalGEM, the state’s slow moving regulatory body for oil and gas, to implement protections on its own accord.

CIPA originally filed the paperwork for the referendum just three days after Governor Gavin Newsom signed the oil setback bill into law in September, and has spent months collecting the more than 600,000 signatures needed for the initiative to be formally included on the 2024 ballot; Stop the Energy Shutdown, the CIPA-run committee sponsoring the referendum effort, has now collected over 978,000. Over the next few months, California’s secretary of state and county registrars will count and certify the signatures.

“What we’re seeing right now is the last gasp of a dying industry that is willing to do anything to get what they want,” said Kobi Naseck, a coalition coordinator with Voices in Solidarity Against Oil in Neighborhoods, or VISIÓN.

While 2024 seems far away, experts told Grist that the new referendum, by even qualifying for the ballot, could have consequences starting immediately. Instead of going into effect January 1, the protections established by SB 1137 will be delayed until after the vote, buying fossil fuel companies two more years to reap profits from their wells. “What we could see in the next two years is a big run on permits and a huge amount of drilling, in anticipation of a loss for Big Oil in 2024,” said Naseck.

In California, there are 2.7 million people who live within 3,200 feet, a little over a half mile, of active oil wells; Black and Brown residents account for 70 percent of that total. The biggest funders of Stop the Energy Shutdown are oil companies that operate in low-income neighborhoods and places where communities of color live and work.

Sentinel Peak Resources, Signal Hill Petroleum, and E&B Natural Resources Management Corp., which together contributed over $10 million to the referendum campaign, have a combined 3,186 wells within the setback zones recommended by public health researchers and designated in the new bill. This past year, Signal and E&B received notices of violation for methane and noxious gas leaks that exceeded air safety standards; E&B made the news earlier this month for resisting excessive pressure warnings ahead of an oil well blowout in a residential area of Bakersfield that injured an employee. In total, the Stop the Energy Shutdown coalition of “small business owners, concerned taxpayers, local energy producers, and CIPA,” raised over $20 million as of December 2 to overturn the regulation that would protect people from these types of hazards.

In a statement to Grist, Rock Zierman, the chief executive officer of CIPA, said the legislative hearings on the bill did not adequately consider job losses, and that setback advocates “are trying to eliminate the cleanest oil production in the world, while destroying the rainforest and increasing greenhouse gas emissions by making California more dependent on foreign oil.”

As Michael Hiltzik notes in the Los Angeles Times, nearly four-fifths of California’s oil already comes from overseas, and oil production in the state has been declining for years because the supply in the ground is depleting. In addition, at the senate hearing on SB 1137 in August, state Senator Henry Stern procured a statement from Nemonte Nenquimo, a Waorani leader involved in the tribe’s lawsuit to stop oil drilling in the Amazon due to its impacts on local people and ecosystems; Nenquimo expressed solidarity with the communities living near backyard oil wells in California.

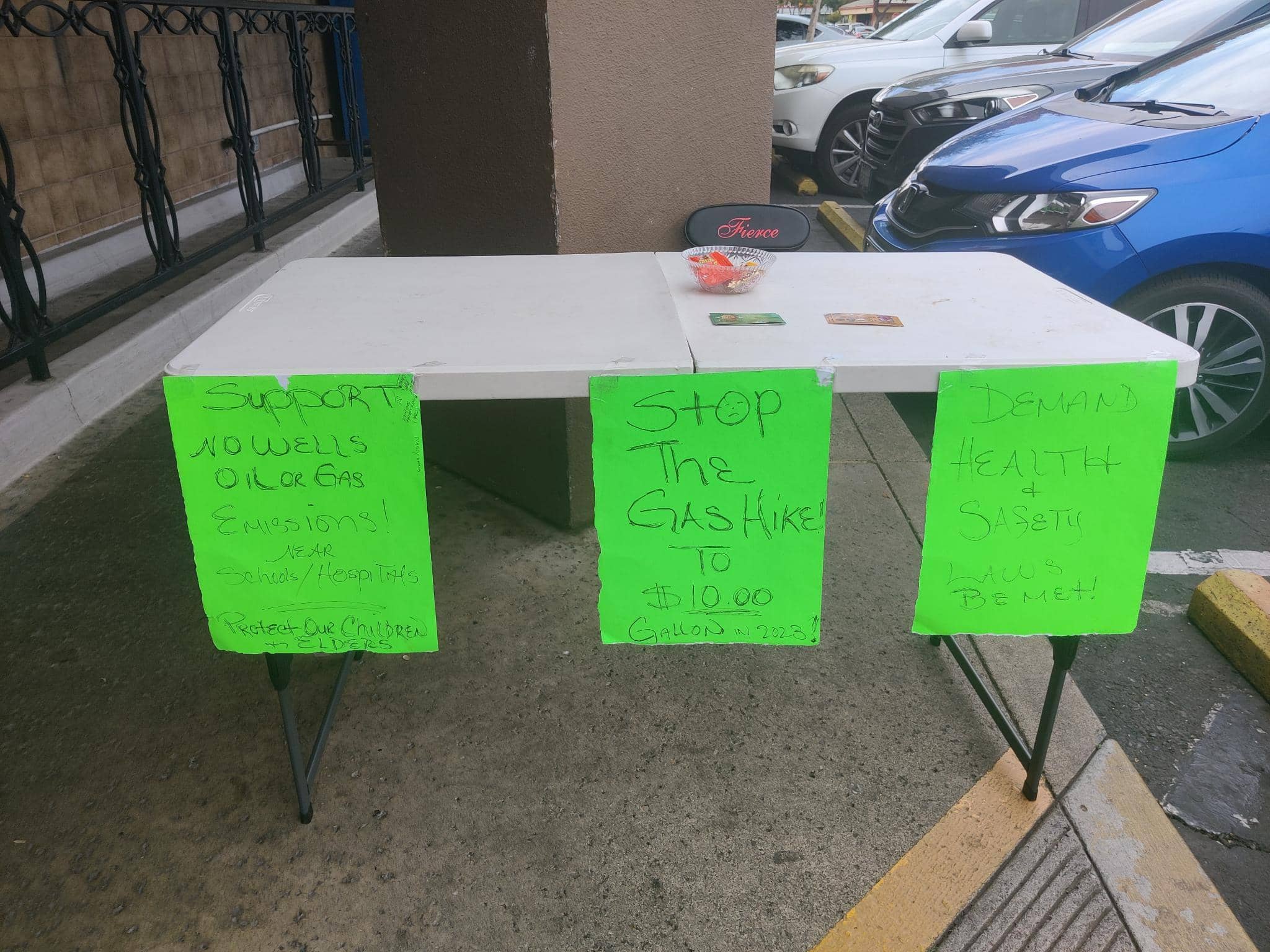

In the purest sense, getting an initiative or referendum on the state ballot is a way for residents to bring new laws directly to the public for vote. But in reality, it is an incredibly costly undertaking, referred to by detractors as a tool used mostly by special interest groups, such as industry, to get around legislation. In the case of the oil industry’s ballot push, residents and advocacy groups have reported numerous counts of petitioners sharing misleading information and outright lying about the purpose of the measure outside grocery stores across California. Inside Climate News reported on petitioners saying the oil-backed ballot measure would lower gas prices and that it would stop the practice of neighborhood drilling. It would in fact do the opposite.

“The office of the Secretary of State has received a large number of complaints,” said Hollin Kretzmann, an attorney focused on oil and gas issues with the Center for Biological Diversity. The Secretary of State has already launched an investigation, and advocates are calling for the state Attorney General to investigate the issue as well, said Naseck.

Setback advocates expect to know the final status of the referendum effort and the validity of its signatures sometime between the end of February and April.

If it does qualify, there is one last line of defense for communities. California’s regulatory body for oil and gas, CalGEM, was in the process of drafting a public health rule to create statewide buffer zones when SB 1137 was passed into law. According to advocates, CalGEM’s rulemaking process had been dragging on for years, and the bill was an attempt to force the agency to take swifter and more decisive action.

“Even before SB 1137, we never needed a law on the books for CalGEM to do the right thing and regulate oil and gas operators near homes and schools,” said Naseck. Last year, the agency did deny a host of permits on the grounds of climate justice and public health. At the same time, they also permitted a set of new wells in Santa Clarita in Los Angeles County, leading to a lawsuit.

On Monday, the agency issued a notice of proposed emergency rulemaking action to implement setbacks, indicating that it plans to move forward with fulfilling its mandate under SB 1137. “If CalGEM wanted a permanent protection and safety buffer zone, they would continue with the draft rulemaking process that has been long delayed,” said Naseck.

“All eyes will be on the agency to see what happens in the new year,” he added.