This story is a collaboration with The Mercury News and East Bay Times, whose mission is to inform Bay Area communities by telling accurate and compelling stories that make an impact.

It was the Zoom call from hell.

About a dozen residents from Richmond, a small city in California’s Bay Area, had logged onto the video conferencing application late one June evening last year to discuss improving air quality in their neighborhoods. Tensions were running high. The audio kept cutting out for some who had spotty internet connections. Others struggled to mute and unmute themselves when they wanted to speak. The residents talked over each other, some barely concealing contempt for others on the call. One participant even burst into tears.

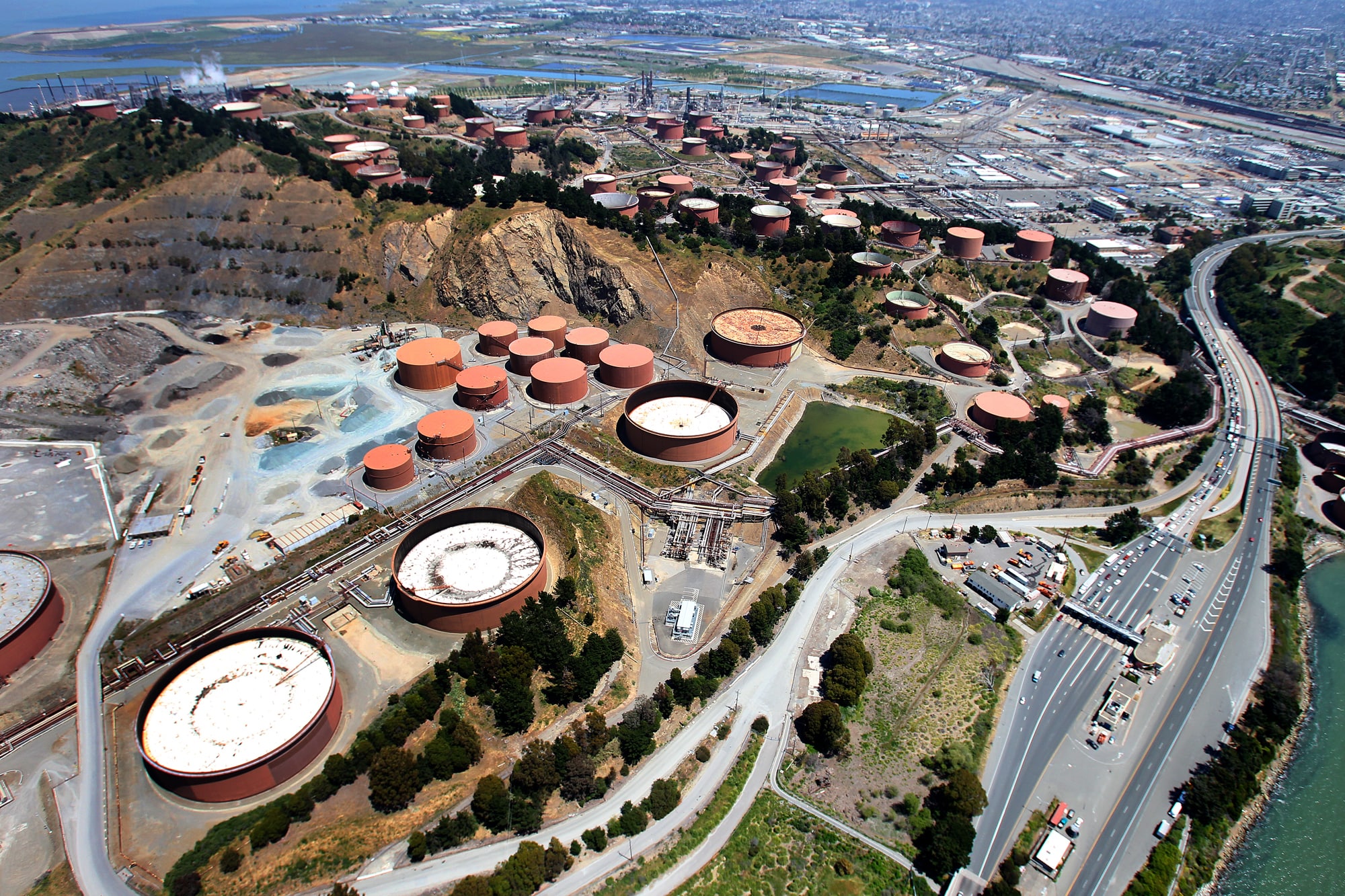

Andrés Soto, one of the most vocal community members on the call, watched as the almost two-hour meeting devolved into chaos. A 66-year-old environmental advocate and organizer for the nonprofit Communities for a Better Environment, he was calling from his desk at home in nearby Benicia. The mosaic of family photos framing his head — a cherubic one-year-old Soto smiling cheekily at the camera, a middle-aged Soto in a top hat flanked by his two sons — belied his commanding personality: Born in Berkeley to activist parents, he is a proud Chicano who grew up in Richmond and nearby San Pablo and has spent his adult life joining progressive causes. Most recently he’s been working on issues related to environmental justice. For residents in Richmond, those fights typically center around the 2,900-acre Chevron refinery on the western edge of town, which has paid millions in fines and faced criminal charges for negligence and environmental damages over the last decade.

The oil behemoth has operated the facility since 1902 and is the largest employer in the working class, heavily industrialized city, making it inextricably tied to the community’s future. Over time, Chevron has donated to more than 80 local organizations, and it even funds a local newspaper, the Richmond Standard, which features cheery headlines about Chevron’s donations to COVID-19 relief funds.

In addition to this largess, the Chevron refinery also belches thousands of pounds of noxious and carcinogenic gases into Richmond’s air every day. Over the years, residents have had to flee from numerous fires and explosions at the refinery. Six days after Soto started at Communities for Better Environment in 2012, a pipe exploded and the facility caught fire. Soto had just returned from work when his partner told him to look out the window.

“I went outside and I saw the big cloud of smoke,” he recalled. His organizer training kicked in, and he immediately sprang into action, calling community members and telling them to stay indoors. He knew the smoke would carry particulate matter and other toxic chemicals that could trigger asthma attacks and worsen respiratory issues. A county health report published months later found that more than 15,000 people sought treatment at a nearby hospital in the days after the fire.

That sort of repeated exposure to pollution from the refinery and other industrial operations in the community has taken a toll on Richmond’s majority Black, Hispanic, and Asian residents. The city consistently scores among the worst in the state for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Neighborhoods adjacent to Chevron are in the 99th percentile for asthma rates in the state.

Caps on pollution from the refinery would improve residents’ health, but for years the company’s lobbying efforts and election-year spending sprees have scuttled effective monitoring and regulation. Until the 2012 fire, the city had no particulate matter monitors; the closest one, in San Pablo, operated just once every 12 days, often missing times when the refinery spewed more pollutants than it’s allowed to.

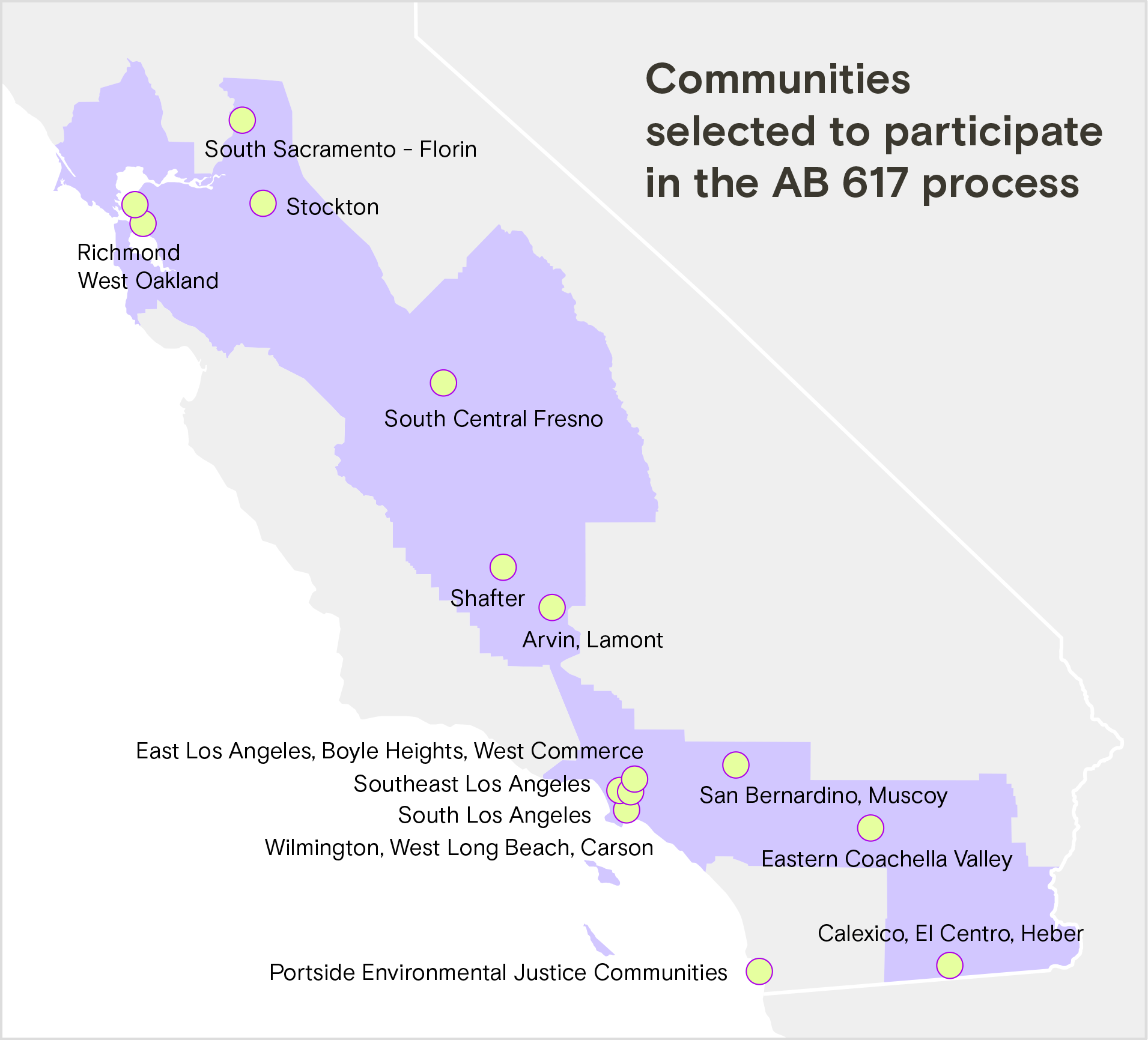

On the Zoom call, Soto was furious about what he saw as more Chevron meddling. The June 2020 call was part of a series of meetings that Richmond community members had taken up under the aegis of AB 617, a piece of landmark legislation that was passed in 2017 as a companion to the state’s cap-and-trade law. The measure has since funneled hundreds of millions of dollars to 15 low-income communities of color across California — including Richmond — allowing them to install dozens of air monitors, collect air-quality data, and craft plans to place limits on toxic emissions from the refineries and industrial facilities in their neighborhoods.

Heralded by lawmakers and academics as “the new frontier in air quality management,” the law aimed to put the community in the driver’s seat. No longer would bureaucrats in Sacramento set the agenda. For the first time, state regulators, policymakers, and industry would take instructions from communities on how best to clean up the air.

But more than three years in, AB 617 hasn’t delivered on its promises — and environmental advocates say it doesn’t appear it will. One key reason: There’s no recourse if plans developed under the law don’t actually reduce pollution. Of the 10 communities that were initially selected by state regulators in 2018, just one — Wilmington, a neighborhood that sits by the Port of Los Angeles — initiated a concrete goal to reduce emissions. In at least four other Central and Southern California communities, such as Fresno, Shafter, and East Los Angeles, the plans simply list actions agencies were already going to carry out and meager incentives to cut pollution that do not guarantee concrete emission reductions.

According to a May report by the California Environmental Justice Alliance, whose members participated in AB 617 planning in five communities, the process required residents to spend hundreds of hours in meetings, but the resulting plans “are mostly unenforceable, and thus may have little impact to the harmful air they breathe.” The report ends with a stark conclusion that AB 617 “should not be replicated in other jurisdictions.”

Instead of real emission reductions, AB 617 has created a long-winded, bureaucratic process that looks set to generate reams of new air quality data but little new regulation — as in Richmond, which has so far only approved air quality monitoring that government regulators were already planning on funding. Gwen Ottinger, a researcher at Drexel University who spearheaded an analysis of two years of air-monitoring data in Richmond, said it’s one of the biggest shortcomings of the law. “AB 617 doesn’t cap [emissions],” she said. “It doesn’t draw any lines in the sand.”

These shortcomings may well be inherent to the bill’s design. Polluting industries’ heavy influence on California’s cap-and-trade bill is well-known, but their proposal to include an environmental justice component along the lines of AB 617 has not been widely reported. Indeed, it was one of many ideas floated by a lobbying firm hired by the oil and gas industry — including Chevron itself — in 2017. Alongside proposals that weakened the proposed cap-and-trade law, the firm suggested creating a “community focused monitoring and control program to address toxic/criteria air pollutants.”

The California Air Resources Board, or CARB, is the state agency that selects communities for AB 617 funding and has final approval over their plans. When presented with critiques of the environmental justice law, CARB’s Director of the Office of Community Air Protection, Deldi Reyes, told Grist “it’s way too early to start talking about failures of the program.” She called the AB 617 process “an 11-year commitment” that cannot be fairly judged at the three-year mark. Reyes also said that the agency is “trying to learn from the challenges,” pointing to pollution-mitigating provisions the state has approved after community input, including one cutting emissions from warehouse activities in four Southern California communities.

Perhaps as a result of this outlook, CARB is moving full speed ahead to expand AB 617 work. The agency has added five more communities to the roster after selecting an initial 10 in 2018. Paulina Torres, an attorney with the Center on Race, Poverty, and the Environment, worries that as more communities across the state are selected, they may pour their time and resources into the process but end up with little to show for it. Given California’s reputation as a climate leader, other states may draw inspiration from AB 617, too.

“I have serious concerns and hesitations,” Torres said. “How did we hop to the next community without addressing the existing failures in the last community?”

Soto was one of several activists in Richmond who was long aware of AB 617’s limitations. He knew there were layers of bureaucracy to wade through, but the work still had the potential to move the needle on pollution in their community. Even small reductions had the potential to save lives.

Here’s how the process typically unfolds: After being chosen for AB 617 participation by the state, a community first develops an air quality monitoring plan to better understand the sources of its pollution. A group of community members works with the local air district to design the plan, which the district then implements with money allocated through the law. While that plan is being developed or after, the district also selects members for a steering committee that will ultimately craft what the law calls a Community Emissions Reduction Plan. In other words, there are quite a few steps before even a blueprint for reducing pollution is on the table.

In Richmond, the district convened a group of residents — called the Community Design Team — to draw up a process to select members for the steering committee. For months, however, that team was bogged down in what many believed should have been an uncontentious topic. Given the history of industry influence in Richmond, the design team was contemplating requiring applicants to fill out a conflict-of-interest form before being considered for the steering committee. The 10-member group was split 6 to 4, with the majority pushing for a strong policy that weeded out residents with ties to Chevron and other industry polluters.

The majority, who dubbed themselves the “environmental justice caucus,” consisted of four longtime white residents, Soto, and Naama Raz-Yaseef, an environmental scientist who had recently moved to town. In the minority, however, were all three of the group’s Black members, as well as Oscar Garcia, a Chevron employee. They’d struck a more conciliatory tone on Chevron and were appalled at accusations by a member of the environmental justice caucus that they had “been bought off.”

“The disturbing thing is that it became a fight between environmental justice and the Black community,” said Raz-Yaseef, a researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “I still don’t understand how that happened.”

As tensions simmered on that June call, Soto and others in the majority pushed for a vote on the conflict-of-interest form. But a representative from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD), the local air district regulating emissions from stationary sources like the Chevron refinery, wouldn’t allow a vote. Instead, the rep wanted to establish a consensus, even as one appeared impossible among members who were barely on speaking terms outside of meetings. That decision, along with others that the district made, would later be deemed part of a “flawed” process by BAAQMD board members who acknowledged that the district had exacerbated “tension and adversity” among community members.

Soto, for his part, accused BAAQMD of putting its thumb on the scale to favor industry. After the June call, the district held no design team meetings for the next two months, while the group remained at an impasse over the conflict-of-interest form. The group was finally allowed to vote after the district hired Veronica Eady, a well-respected environmental lawyer, to oversee its equity efforts. The form was approved after seven months of quibbling.

Eady is quick to acknowledge “missteps” the district made last year, but she defended the process’ pace as necessary for crafting an effective plan. “We’ve been trying to move at the speed necessary to really create a deep partnership and a sense of trust and respect between the community and the air district,” she said, emphasizing that the ultimate goal remains tangible improvements in air quality.

Asked whether he thought Richmond’s air quality would ever improve, Soto demurred: “It depends.” Efforts to monitor air quality in Richmond stretch back to the 1990s, and residents have become accustomed to being asked to participate in air pollution and public health studies. They regularly show up at legislative hearings to advocate for cleaner air. AB 617, he said, was simply the latest time-consuming and expensive ask of the community.

Years of unfulfilled promises have made Soto a cynic in the eyes of some. In his view, he’s a realist. “AB 617 is working exactly as it was designed,” Soto told Grist. “We knew it was going to be a delay tactic.”

Richmond was exactly the sort of community that AB 617 was designed to transform. Incorporated in 1905, the city’s early founders had a dream of making it the “Pittsburgh of the West.” They wooed shipbuilders to its deepwater port, along with auto manufacturers, railroad companies, and others so aggressively that ultimately the city agreed to incentives that left Richmond with a meager tax base to cover basic infrastructure needs. Standard Oil began building the massive refinery that eventually became Chevron’s in 1901. The facility became the second-biggest refinery in the world and the city’s largest and most influential employer.

With the second great migration, economically depressed African Americans from the South began moving to Richmond, lured by the promise of steady work. As a result, Richmond’s population quadrupled between 1940 and 1943. The new residents were relegated to the margins, according to the work of historian Shirley Ann Wilson Moore. Restrictive racial covenants and discriminatory policies enacted by the local housing authority forced Black residents into crowded, underdeveloped neighborhoods near environmental hazards such as the Chevron refinery and a garbage dump.

In the following decades, Richmond residents began connecting the dots between race, industrial pollution, worsening air and water quality, and poor public health — and they began fighting back. Laotian refugees, who began settling in the city after the Vietnam War, joined with Black and Hispanic communities to become a powerful force in Richmond politics from the 1970s on. Headed by three environmental justice organizations — the West County Toxics Coalition, Communities for a Better Environment, and the Asian Pacific Environmental Network — they established a strong cross-cultural alliance that teamed up to hold Chevron accountable.

Most recently, the coalition flexed its muscle during the 2014 Richmond city council elections. For years, Chevron had controlled local politics. But after the 2012 fire, sentiment about the company shifted. It had been charged with six misdemeanor counts of violating labor standards and negligently emitting pollutants and agreed to a $2 million fine as part of a plea deal with state and county prosecutors. For the first time in Richmond’s history, the city council also unanimously decided to sue Chevron for negligence and economic damages to the city. The company responded by pouring more than $3 million into the 2014 city council elections.

But Chevron’s plan backfired. Years of organizing by coalition members had raised awareness among residents of the many ways in which Chevron’s influence had worked against their interests. All three Chevron-backed council candidates flopped at the ballot box. As Soto put it, “People weren’t buying Chevron’s bullshit anymore.” (Tyler Kruzich, a spokesperson for Chevron, did not respond to specific questions about the company’s conduct in Richmond but said that the company has “a long-standing commitment to reduce emissions at our Richmond facility” and that its recent efforts have led to a reduction in particulate matter emissions.)

Chevron’s influence doesn’t end at Richmond’s city limits: It also donates to state legislators, giving millions of dollars primarily to conservatives and moderate Democrats. That sort of spending came in handy in 2017, when the California legislature was debating extending its cap-and-trade law, as well as passing AB 617.

In the weeks leading up to the passage of those bills, Soto’s Communities for a Better Environment and other grassroots environmental organizations were on the verge of getting BAAQMD to cap emissions from five refineries in the Bay Area, including the Chevron facility. BAAQMD had proposed a new regulation, called Rule 12-16, after years of careful study by air district staff, as well as organizing and lobbying by community members. The rule would have required Chevron and other refineries to limit greenhouse gas emissions as well as three other toxic pollutants that are primary drivers of poor respiratory and cardiovascular health.

But Chevron performed an end run around the environmental groups. At the last minute, Chevron and lobbyists with the Western States Petroleum Association, an oil industry trade group, inserted a provision in the bill to renew California’s cap-and-trade program that stripped local air districts’ authority to directly regulate greenhouse gas emissions. It effectively killed Rule 12-16.

The renewal of cap-and-trade was of paramount importance to then-Governor Jerry Brown. When negotiations on the legislation began in earnest in early 2017, Brown was completing his fourth and final term, and looking to cement his legacy as a climate leader.

When designed properly, cap-and-trade is supposed to limit emissions statewide and slowly ratchet them down, forcing industrial polluters to find ways to cut emissions or shut down altogether. Companies are allowed to purchase pollution credits from a limited pool, and the money raised from the sales is funneled back into community projects.

But in California, its implementation had been mired in controversy. The state had granted more emission allowances than major polluters needed, and environmental justice advocates warned that the excess pollution would end up hurting communities of color. A 2018 study (co-authored by Grist board member Rachel Morello-Frosch) found that though overall emissions declined statewide, pollution increased in communities of color located close to emitters. The study did not attribute the increase to cap-and-trade, but advocates called it the “I told you so” report for confirming their fears that the most vulnerable California communities would not benefit from the signature bill.

For the cap-and-trade bill to pass, it needed support from a two-thirds majority of state legislators. Early versions of the bill were opposed by both Republicans and progressive Democrats — the former because it increased taxes and regulations on business; the latter sided with environmental justice advocates who said that it would not improve air quality in communities like Richmond.

The combination of Republican holdouts, the oil industry gunning for fewer limits on carbon emissions, and Brown’s desperation to pass climate legislation of some kind led to the main cap-and-trade bill becoming riddled with giveaways and loopholes. Killing Rule 12-16 was one such compromise. Others included setting a high cap on emissions and handing additional pollution permits to companies that the state deems are at high risk of moving out of state.

Even as the main cap-and-trade bill was being watered down, Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia, a Democrat from the Los Angeles area and an environmental justice champion, emerged with an olive branch for advocates like Soto: AB 617. But it, too, was heavily influenced by industry — in fact, the idea to engage disadvantaged communities to come up with air quality solutions came directly from major fossil fuel players. A 12-page Powerpoint presentation produced by Latham & Watkins, a lobbying firm representing Chevron and the larger oil industry, floated the idea along with a wish list for the cap-and-trade bill. In it, lobbyists suggested creating a “community focused monitoring and control program” to address pollutant hotspots with air districts establishing “a community advisory board.”

According to Garcia, Governor Brown’s office shopped around an early version of AB 617 that had many provisions the oil and gas industry had proposed to her in previous debates. It included money for setting up monitoring systems in disadvantaged communities, but did not have mechanisms to reduce pollution. “I was like, ‘that’s not enough,’” Garcia recalled. “Because the Republicans were at the table, it made it much harder for us to try to get much of anything.”

The resulting bill, Garcia admits, was a “compromise” and “a down payment” that she hoped could be improved upon. Since only a small number of communities are picked to participate in AB 617 and funding was limited, it pitted communities against each other over a finite pot of money. Funding for air monitoring and implementing the emission reduction plans is unreliable because it’s tied to cap-and-trade auction results. When fewer pollution credits are sold by the state, there’s less money available for communities. Funding for 2019-2020, for example, was revised down from $245 million to $209 million after reduced demand for fossil fuels during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Perhaps most importantly, as Drexel’s Gwen Ottinger noted, the bill lacks strict requirements.

AB 617’s early results underscore these shortcomings. In Fresno, the second-most polluted city in the country as measured by year-round particulate pollution, the plan does not have any measurable targets for reducing emissions from heavy-duty vehicles or industrial sources, which are major sources of pollution in the county. Instead, the plan expands voluntary rebate programs for swapping older, dirty trucks and cars with electric vehicles and money for residents to replace wood-burning stoves.

Similarly, a plan for Shafter, a town in the Central Valley that is surrounded by agricultural fields and oil and gas operations, initially did not include any plans to regulate pesticide use, despite community members repeatedly raising the issue as a top priority. After a tough fight with the local air district to consider airborne pesticides a toxic pollutant — and therefore under AB 617 jurisdiction — the community included a pilot program to notify residents of pesticide application schedules. But the county agricultural commissioner has refused to implement the plan, stating that a notification requirement “is clearly not within the scope of AB 617.” Other proposals in the Shafter plan include community events to increase awareness about the district’s incentives and car-sharing programs. There are no clear mandates to cut pollution.

Katie Valenzuela, a former policy and political director for the California Environmental Justice Alliance, said that she’d attended numerous meetings where air district staff questioned whether AB 617 even required plans that led to a measurable improvement in air quality. “It kind of makes you go, ‘What?’” she said.

While Valenzuela said that was a clear misinterpretation of the bill, she laid the blame at the feet of CARB, which she said wasn’t doing enough to hold air districts accountable when they obstructed communities from developing strong plans. CARB oversees local air districts, and all AB 617 community monitoring and emission reductions plans require final approval from the agency’s board. “What we’ve heard time and time again from communities is it’s not meeting the law, and CARB is still approving the plans,” Valenzuela said.

Valenzuela, who was heavily involved in cap-and-trade negotiations, said that the state now sees AB 617 as the vehicle to address all environmental justice concerns. When advocates raise the disproportionate effects of a new policy on communities of color, she said that they’re told AB 617 will address it.

“What was done functionally was exactly what everybody was worried about,” she said. “We’ve made it more complex for communities to advocate.”

AB 617 has delivered tangible results in one aspect: providing state-of-the-art air quality monitoring to vulnerable communities. Richmond provides an illustrative example of that element’s successes — and limits.

During the massive 2012 fire that led to the political revolt against the Chevron refinery, both Chevron and BAAQMD issued one mantra: The air was safe to breathe. Even as Richmond residents checked into hospitals and clinics in droves, complaining of chest pain and difficulty breathing, the air district reassured the public that the pollutants detected by its monitoring program were “not a significant health concern.”

BAAQMD reached that conclusion based on spotty air-quality data. The monitor closest to the refinery capable of detecting toxic pollutants had been turned off. To save operational costs, the monitor collected data just once every 12 days. As a result, the district relied on samples it collected more than 24 hours after the fire, as well as on data from monitors miles away.

It’s a stark example of inadequate and poorly designed air monitoring — and a key reason why AB 617 funds additional air quality assessment in communities. Other systems across the country are similarly lackluster: A bombshell Reuters investigation last year found that the nation’s air monitors, which are routinely used to determine local air quality — and relied upon by those with respiratory diseases — are routinely failing to pick up spikes in pollution from fires and explosions. A report by the Government Accountability Office, Congress’ investigative arm, published late last year found that funding for state and local monitoring has decreased by 20 percent since 2004.

After the 2012 fire, Chevron paid to have an air-quality monitoring company install and run six sets of monitors in Richmond, but because they were operated by Chevron’s contractor, the air district couldn’t use the data from them to impose fines or penalties. What’s more, as Ottinger, the Drexel University researcher, discovered, the contractor posted the air monitor readings on a website where they were voluminous, difficult to decipher, and disappeared into a virtual black hole with each new batch of data posted.

AB 617 is supposed to rectify these data gaps. As part of the law’s implementation in Richmond, CARB and the local air district have sponsored two groups of nonprofits, which have installed more than 100 small monitors outside residents’ homes and near childcare centers and schools in Richmond and neighboring San Pablo. Every minute, the shoebox-sized devices measure the levels of particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and ozone — three of the most harmful pollutants to human health. A third company that has fitted cars with air monitors has been driving around Richmond to collect even more detailed, block-level data. Analysis of the data so far has led the community to identify two pollution hotspots near industrial facilities and major highways.

However, a key question — whether these findings will ever be used to develop regulations that cut emissions — still looms large over the process. The AB 617 process is generating useful data, yet Richmond remains one of just two communities of the 10 selected to receive funding from the law that doesn’t yet have an emissions reduction plan. Soto and others believe that’s at least in part due to corporate influence over the process.

In 2019, a group of 35 residents and representatives of various polluting companies, including Chevron and the nearby Levin coal terminal, were selected to approve an air monitoring plan under the aegis of AB 617. A few months after the group was formed, it was given the chance to begin work on an emissions-reductions plan. Instead, the group voted to continue air monitoring work. It was a delay that would leave Richmond residents breathing polluted air for another year. When the group finally concluded its work in July 2020, it had little to show for the previous year and a half.

“We’re generating more and more and more ambient air data, especially at the community level, without the same kind of attention being put into: ‘So then what do you do with that data?’” said Ottinger, the Drexel University professor. “Does it change anything?”

“We know Chevron is the single largest emitter of greenhouse gases in Northern California,” said Soto. “We don’t need to have a fully completed portrait of the pollution in Richmond to know that we need to do something to drastically reduce the pollution coming from Chevron. That’s our frustration.”

In December, six months after the disastrous June Zoom call, the Richmond residents were no closer to finding common ground. If anything, the group’s divisions had grown deeper. Oscar Garcia, one of the ten Richmond residents on the call, dropped a bombshell that led to further polarization. In a three-page letter to state legislators signed by him and three other Richmond neighborhood council presidents, he accused Soto and five other participants on the call — the so-called “EJ caucus” — of racial bias and “systematic disenfranchisement of Black and Brown communities.”

Garcia, who was born and raised in the Iron Triangle, a residential area adjacent to the Chevron refinery, is president of the neighborhood council and has been active in the city’s politics. He ran for a seat on Richmond’s city council and now serves on its Community Police Review Commission. For the past nine years, he has also worked at Chevron’s headquarters in San Ramon and is in charge of coordinating compliance with California’s cap-and-trade program at the Richmond refinery.

For Soto and others in the EJ caucus, Garcia is the walking embodiment of the conflict of interest that they were trying to root out. They had seen once already how Chevron and other polluting industries had delayed AB 617 work on the air monitoring committee and were determined to not let history repeat itself when choosing the steering committee that would draft an emissions reductions plan. (Garcia did not respond to multiple requests for comment; Kruzich, the Chevron spokesperson, said that participation by employees representing community perspectives “is independent of any Chevron participation in the AB 617 process.”)

For many Richmond residents who are clamoring for something to be done about the Chevron plant, Garcia may always be perceived as biased. Someone like Willie Robinson, on the other hand, is harder to peg. Robinson is the president of the Richmond chapter of the NAACP, which has received tens of thousands of dollars in donations from Chevron. He routinely sided with Garcia and is one of the three Black members of the group that Garcia referenced in his December letter.

A longtime resident of Richmond, Robinson is appalled that Soto and others question his commitment to his community. “If Chevron gave us a few thousand dollars for a fundraiser in February, I’m going to be beholden to Chevron when it comes to my air?” Robinson said in an interview with Grist. “The peanuts that Chevron puts in this community don’t amount to nothing.”

Nevertheless, Robinson doesn’t want to see Chevron or any other company shutter in a city desperate for tax revenue and economic activity. “What would be a measured way to get them to change without necessarily forcing them out of business?” he asked rhetorically.

As a result of Garcia’s letter, Veronica Eady, the air district lawyer who had intervened once already over the summer to break the impasse over the conflict-of-interest form, was called in to settle the dispute in mid-December. Over the course of more than three hours, the community members described a year of division and chaos. Garcia implored the air district to promote a consensus-based approach to choosing steering committee members, to prevent the EJ caucus from using its majority to dominate the process. Randy Joseph, a Black resident who currently serves on the city’s police task force, said that he was “hurt” that the EJ caucus regularly met separately to strategize. Soto struck a conciliatory note, saying, “We want to work with the fellow members of the design team.”

By the end of the meeting, air district board members began apologizing for how their decisions derailed the AB 617 process. But the next step they took promised to slow the process even more: In order to prevent independent meetings like those the EJ caucus was accused of, the board voted to give the steering committee a legal designation that makes its meetings open to the public and more transparent. Regardless of the decision’s merits, it adds another layer of bureaucracy for community members to navigate.

Richmond is running out of time. The official deadline to have a plan in place is February 2022. The division over the conflict-of-interest form and mismanagement by the district meant the committee to design the plan wasn’t even in place until this past March. The 30-member committee is unlikely to finalize a plan in the four months before the 2022 deadline.

So far, the committee has met seven times, discussed its responsibilities under AB 617, and selected co-chairs to lead the process. Substantive work on ways to improve air quality in Richmond has not begun.

Eady said that CARB would likely grant an extension to Richmond, just as it has to other communities bogged down in the logistics of AB 617. She said it was “pretty remarkable” that the community had established “a very functional steering committee” after all.

Meanwhile, Soto is watching from the sidelines. The air district has prohibited him, Garcia, and the remaining members of the community design team from joining the emissions reductions committee. But he’s more hopeful now. Eady and her air district colleagues are “turning lemons into lemonade the best they can,” he said.

Soto maintains, however, that the air district has the authority to require more stringent emission caps on Chevron and other polluters. The AB 617 process is just an excuse not to use it, in his view: “Air districts already have profound authority to regulate pollutants and have chosen not to.”

Yvette Cabrera contributed reporting to this story.

Correction: This post has been updated to correct language identifying Naama Raz-Yaseef and Katie Valenzuela.