Every minute, a new customer is hooked up to the natural gas system, says Karen Harbert, president of the American Gas Association, or AGA, the primary trade association for U.S. gas utilities.

Today, that’s a major problem for the climate. Leaks are common throughout the natural gas system, from wells, pipelines, and appliances, and they release the powerful greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere. When natural gas is ultimately burned in a heater or stove, carbon dioxide is emitted. All told, residential and commercial use of gas was responsible for about 10 percent of U.S. emissions in 2019. In colder parts of the country that rely primarily on natural gas heating, it makes up a much larger portion of emissions.

But at a press conference on Tuesday, Harbert told reporters that the natural gas system can grow by 24 percent over the next three decades while at the same time becoming cleaner, and eventually not contribute to climate change at all. That’s the key finding of the AGA’s new “Net-Zero Emissions Opportunities for Gas Utilities” report.

The report comes as many cities and states with climate goals are passing policies and creating incentives to staunch the tide of new natural gas users by encouraging people to install appliances that can run on clean electricity, like heat pumps and induction stoves. The shift threatens gas utilities’ bottom line, and the industry is pushing for solutions that utilize their existing infrastructure.

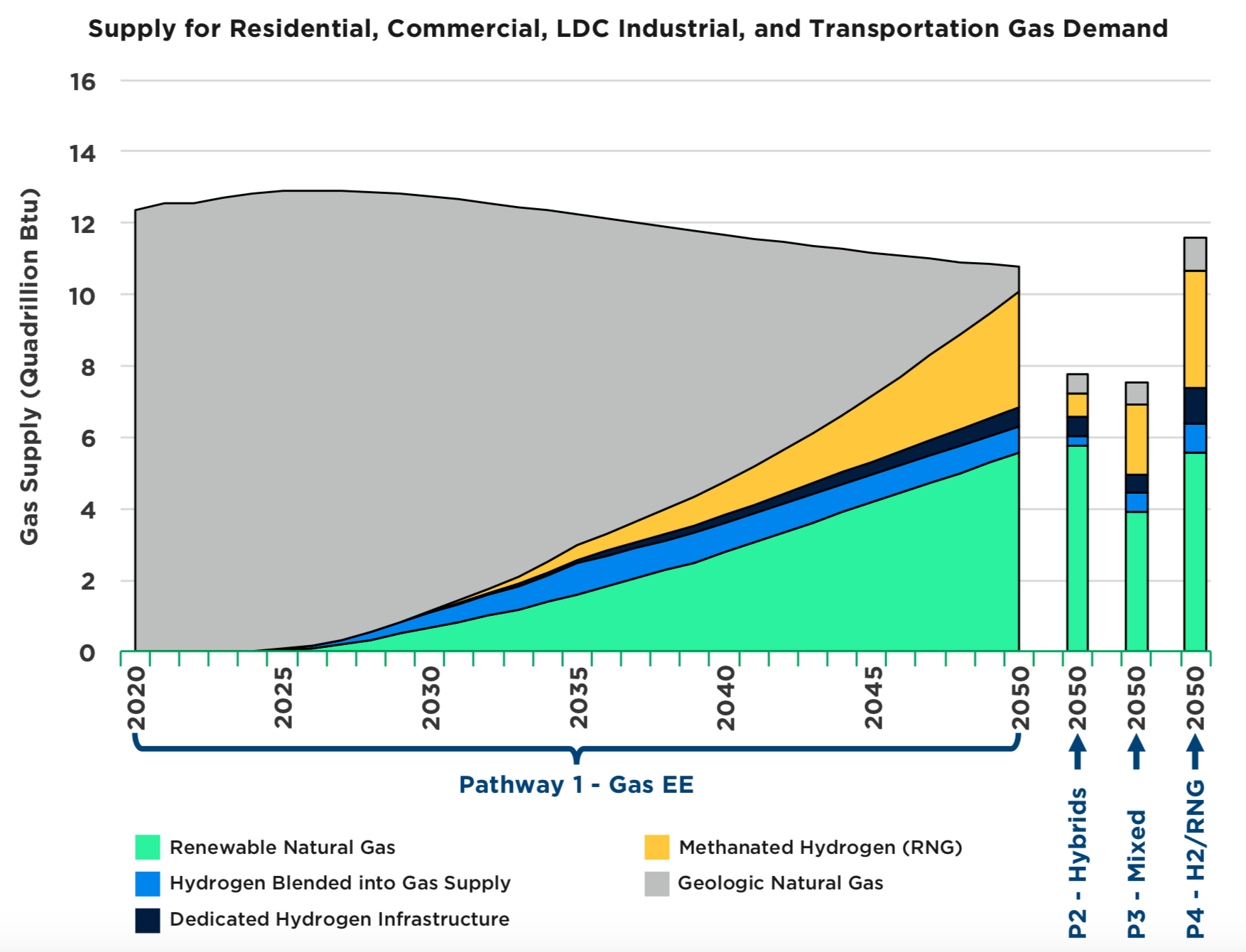

The AGA report outlines four potential pathways that gas utilities could follow to zero out their emissions by 2050. All four would require a radical transformation of the industry, with the amount of energy supplied by fossil natural gas dropping from 12 quadrillion British thermal units today down to 1 quadrillion or less by mid-century.

All the pathways feature a similar set of solutions but vary in how much they rely on each one. The AGA is proposing that utilities reduce their energy demand through energy efficiency programs; repurpose the existing pipeline system to deliver alternative gases that have a lower (but not zero) carbon footprint, like biogas or a blend of natural gas and hydrogen; build new pipelines in select areas that can carry pure hydrogen; and ramp up leak detection and pipe replacement programs to reduce methane emissions.

The AGA also sees carbon capture playing a role to cut emissions from natural gas use in the industrial sector and in the production of hydrogen. All four of the industry group’s pathways rely on carbon capture and carbon offsets to eliminate the last 8 to 14 percent of gas utilities’ current emissions.

Electrification could still play a minor role in the AGA’s vision of the future. Two of the pathways involve a small portion of customers switching to electric appliances, although one of them assumes these will be hybrid systems that use gas heating as a backup when it gets really cold.

Richard Meyer, vice president of energy markets analysis and standards at the AGA, emphasized to reporters that the mix of strategies each utility uses to decarbonize should depend on “highly localized factors” like temperature, energy prices, and building stock.

Mike Henchen, a principal on the carbon-free buildings team at the clean energy research and advocacy group RMI, applauded the trade association for putting out the report. “It’s great to see AGA show clearly that fossil natural gas use needs to mostly disappear by 2050 in America’s gas distribution systems,” he said in an email. “Overall, this is a sign the gas utility industry is working to take decarbonization more seriously.”

Henchen was also glad to see electrification included in the report but said that it gave electric solutions short shrift. Electrification “is a high-confidence strategy for cutting emissions and is the policy direction of a growing number of cities and states,” he said.

The AGA does not consider electrifying all buildings a high-confidence strategy. The trade group’s report notes that widespread electrification may be hindered by local electric grids that can’t meet the added demand, and that there are practical and technological barriers to electrifying very large buildings and running heat pumps on extremely cold days. The report argues that solutions that continue to utilize the existing gas pipeline system could potentially minimize disruption to customers, reduce the cost of decarbonizing, and reduce the uncertainty of going all-in on electrification.

These benefits are purely speculative, however, because the authors did not attempt to estimate the cost of any of the pathways or technology options. The report also acknowledges that there is a great deal of uncertainty as to how much low-carbon gas might be available in the future, as well as about what the options will be to offset emissions. Also absent is any analysis of the potential pollution and public health implications of the solutions and pathways.

Henchen said that other studies have projected that renewable natural gas will remain much more expensive than natural gas in the future. He also expressed skepticism about the AGA’s projection that the industry can grow production of renewable natural gas to 100 times today’s supply, in part by dedicating new crops to biogas production, similar to the way corn is grown for ethanol today.

While the AGA study clarifies how the gas industry is thinking about tackling its climate footprint, it also highlights the need for more detailed analysis to weigh the costs, risks, and potential benefits of different solutions.

“To get the most climate benefit as fast as possible and at a reasonable cost, we’ll need regulatory oversight to weigh these strategies alongside those that go beyond what’s in the report — like widespread electrification,” said Henchen.