This story was produced by Grist and co-published with Verite News.

When a winter storm knocked out Texas’ power grid in 2021, the scale of the devastation it wrought was exacerbated by a singular fact about the Lone Star State: It has its own electric grid, an “energy island” that has long been uniquely isolated from the rest of the country, with just four transmission lines linking it to neighboring states. When the storm hit, Texas was unable to transfer enough emergency power from other electricity markets to keep the lights on. The death toll was in the hundreds.

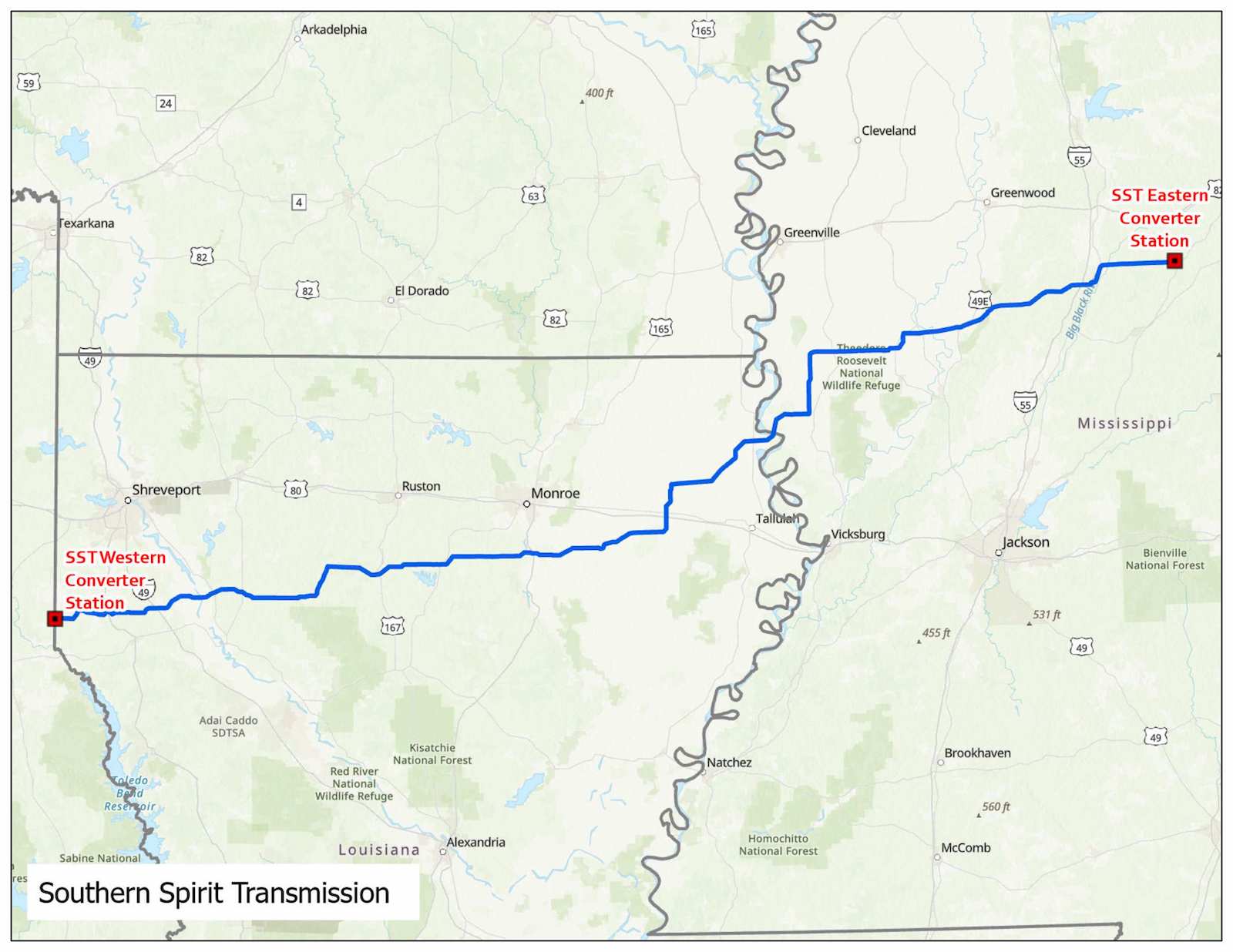

A new multi-billion-dollar infrastructure project could mitigate a similar power emergency in the future. For more than a decade, a private renewables developer, Pattern Energy, has been trying to build a 320-mile transmission line linking Texas’ power grid to the Southeast. But the project, known as Southern Spirit, is now facing opposition in not one but two states it would traverse. Entergy, a utility company whose affiliates in Mississippi and Louisiana would stand to benefit if the new project fails, has raised doubts about the proposal before Mississippi regulators. And even if Mississippi moves forward, a bill in the Louisiana legislature — which was revised at the behest of Entergy — could derail the entire project.

It’s not just Texans who would benefit from more transmission. In order for the U.S. to decarbonize its electricity, a lot more power lines will need to be built across the country. Most crucial is the need for more interregional transmission lines like Southern Spirit — those that connect the nation’s patchwork of energy grids to one another. These are especially important for renewable energy, in part for geographic reasons: The sunny deserts of the Southwest and the gusty plains of Texas and Oklahoma are disproportionately strong producers of solar and wind power, respectively, but most of the potential customers for that power are clustered near the country’s coasts. As a result, the Department of Energy estimates that interregional transmission capacity will need to expand by a factor of five in order to meet the Biden administration’s goal of decarbonizing the power sector by 2035.

But at least two major hurdles stand in the way. The first is that transmission lines sometimes face resistance from landowners along the way, who use the permitting and environmental review processes to block development through litigation or similar means. A second, underappreciated obstacle to new interregional transmission lines is resistance from power companies, who may face a strong disincentive to allow competition in the form of cheap, faraway electricity. On a recent podcast appearance, Mark Lauby, chief engineer at the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, an industry group that regulates the national transmission grid, acknowledged this difficulty, asking, “How do I get a [transmission] line through multiple markets when markets themselves don’t want to compete with other markets?”

“We have substantial challenges within markets, within generators, that are trying to stop the building of transmission. It’s not just permitting; it’s also those folks that feel that they actually get gain out of having that stinking solar stuff a ways away, so they can make more money locally,” Lauby added.

Beyond helping make Texas’ grid resilient, more transmission lines connecting Texas to nearby grids would also help maximize the carbon emissions savings from the state’s abundant wind power. Texas produces more wind energy than any other state, but wind farms are often forced to reduce their output due to inadequate transmission. Building more transmission lines allows producers to produce more wind energy by giving it somewhere to go.

For these reasons, the Southern Spirit project looks like a win-win: If built, it could help decarbonize the region, lower power bills, and protect Texans from a repeat of 2021. It was this last benefit that seemed to finally put some wind in the project’s sails after the storm convinced grid planners at ERCOT, Texas’ energy grid, that more transmission was needed.

But clouds appeared on the horizon last October when Entergy Mississippi expressed concerns around the transmission project in filings before the Mississippi Public Service Commission, which must approve Southern Spirit for the project to move forward.

Neal Kirby, a spokesperson for the Entergy Corporation (the Mississippi utility’s parent company), told Grist in an email that Entergy Mississippi has not taken a position on Southern Spirit overall, but rather has “raised concerns about the impacts of the project on its customers.”

Kirby told Grist that the utility was concerned that “eastbound flows from the line would cause overloads on the system that Southern Spirit would not be required to address or resolve. As a result, Entergy Mississippi homes and businesses may be left with either less reliable electric service or footing the bill for system upgrades to reliably accommodate injections of energy from the new line.”

In other words, Entergy’s system might not be equipped to handle the extra power shipped in from Texas without capital upgrades — and because utilities pass on the costs of approved capital upgrades to consumers as a matter of course, this would mean higher electric bills.

Daniel Tait, a researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute, a nonprofit utility watchdog, called Entergy’s contention that access to Southern Spirit would destabilize the grid and make its energy more costly “absurd and a mask for its anti-competitive behavior.”

Just what might be “anti-competitive” about Entergy’s stance on Southern Spirit was captured in testimony submitted to the Mississippi Public Service Commission by Jeff Dicharry, a transmission planner employed by Entergy, who said the proposed transmission line could force the utility to scale back service at its natural gas plants in Mississippi.

“The predictable result would be an inability to operate [Entergy-operated natural gas plants] Choctaw and Attala during periods with east-bound flow on [Southern Spirit] due to congestion on the transmission system. This would be problematic,” wrote Dicharry.

Tait said Entergy Mississippi’s complaint amounts to “an implicit acknowledgment that this [transmission line] is economically beneficial for customers,” because the Mississippi utility would only reduce operations at its gas plants if the energy flowing in from Texas were cheaper than its own output.

In Louisiana, meanwhile, state legislators are considering a bill that would effectively kill the project by denying expropriation authority — the ability to acquire private property through eminent domain — to all transmission lines that run through the state unless a majority of their power is consumed within the state.

Alan Seabaugh, the bill’s Republican sponsor in the Louisiana state Senate, told Grist his bill was intended to protect North Louisiana landowners from their land being confiscated for a project that does not benefit the state’s residents. The bill passed the Senate by 36 to 1 on March 25 and is pending before the House’s Civil Law and Procedure Committee.

Because Southern Spirit connects Texas to Mississippi, “there is no way to legitimately with a straight face argue that Louisiana’s going to benefit from this one iota,” Seabaugh said, though he clarified that he has not taken a formal position for or against the project.

Adam Renz, Pattern Energy’s director of project development, told Grist that Seabaugh was “very much technically incorrect” in his assessment that Louisiana would not benefit from the transmission line. Though the line does terminate in Mississippi rather than Louisiana, it would deliver energy into a regional grid known as MISO South, which much of Louisiana draws power from.

“The electrons the project will inject into the system can and will flow into the state of Louisiana,” Renz said in an email.

Entergy’s Louisiana subsidiary has not taken a position on Seabaugh’s bill, but the utility was instrumental in the passage of an amendment that exempted any transmission lines within an existing power grid from its purview — effectively ensuring its own future projects would not be affected. “They gave us an amendment to make sure that they were excluded,” Seabaugh said.

Kirby, the Entergy spokesperson, confirmed this. “When the bill author shared the legislation with us, we raised concerns that it may impede projects deemed necessary by MISO or SPP, the entities that are ultimately responsible for making independent determinations about what transmission projects are needed in most of Louisiana,” he said. “Entergy Louisiana suggested to the bill author some language that would address this concern.”

To Davante Lewis, an elected utility regulator in Louisiana who wrote a letter to the state Senate opposing the bill, the amendment effectively “gives the incumbent utilities all the rights to build transmission” and amounts to “pushing interregional transmission costs onto ratepayers,” because utilities have the authority to pass on their capital costs to ratepayers once they get regulatory approval. By contrast, Pattern Energy is privately financing the Southern Spirit project with an investment of more than $2.6 billion, and will recoup that investment from tariffs on power sold over the line once it’s operational. Renz said the project has not received any federal or state incentives.

Lewis, whose commission is currently reviewing a petition for certification by Pattern Energy, has not taken a position on Southern Spirit but said he opposes Seabaugh’s bill because, while it “seems to be directly targeted only at the Southern Spirit transmission line, my concern is what would this mean for transmission buildout” — which he characterized as an important priority for Louisiana ratepayers in the face of growing electricity demand as well as the need to decarbonize.

“Bringing on transmission in order to curb peak demand is vitally important. However, if we look at who has been the biggest objector, it’s been utilities,” Lewis said.