This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

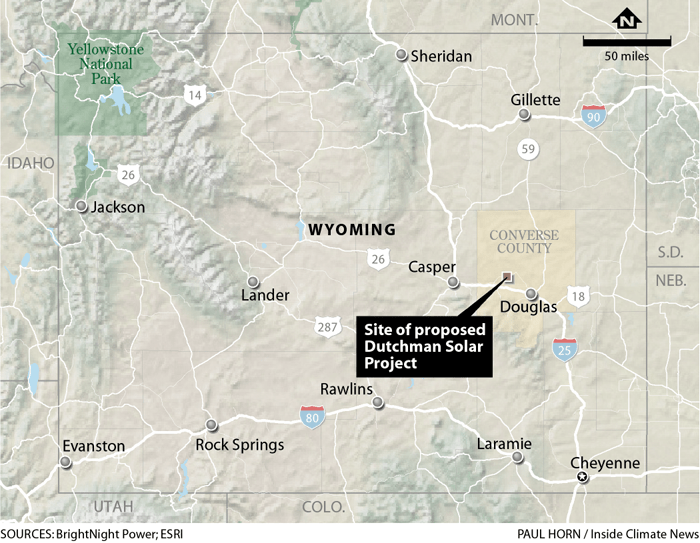

Converse County is one of the most welcoming areas in Wyoming when it comes to clean energy. For roughly every 20 residents, there is one wind turbine, the highest ratio in the state. At a recent County Commissioners meeting, it took another step in diversifying its energy infrastructure, signaling its intent to issue its first solar farm permit to BrightNight.

The global energy company has proposed to build more than 1 million solar panels, a battery storage facility and a few miles of above-ground transmission lines on a 4,738 acres of private land run by the Tillard ranching family near Glenrock. The Dutchman Project, as it is called, is notable neither for its generation nor its storage capacity but for the creatures moseying beneath its panels.

The base of each sun-tracking panel will be several feet off the ground, allowing enough room for the Tillard’s sheep to continue grazing. In a state whose ranching industry predates its inclusion in the union, pairing solar generation with livestock grazing or other agricultural practices, a technique called “agrivoltaics,” could forge an unlikely alliance between two industries — one ancient; the other, high tech — that typically compete for resources.

At the conclusion of their February 6 hearing regarding the Dutchman project, Converse County Commissioners directed the county attorney to draft an order of approval, indicating they would likely grant the project its permit later this month.

“BrightNight is proud to reach today’s permitting milestone. Our project is ideally-sited to deliver valuable capacity to a growing region preparing for significant generation retirements,” said Maribeth Sawchuk, the company’s vice president of communications, in a statement to Inside Climate News. The company is focused on “utility-scale renewable power solutions while also raising the industry standard for community engagement and support.”

The Tillard family could not be reached for comment.

Jim Willox, chairman of the board of Converse County Commissioners and one of the people responsible for reviewing BrightNight’s permit application, remembered being excited to see the company proposing to use an agrivoltaic approach to building solar.

“I think the solar industry has learned that they don’t have to be just bare ground underneath,” he said. “I find that very exciting and a continuation of Wyoming’s view on multiple use.”

Willox has been a Converse County Commissioner for the last 18 years, during which he’s witnessed the rise, fall, and rise again of fossil fuels in the county. When he first started his job, coal production was a huge economic asset to the county. Now, “it’s zero,” he said.

While fossil fuels still play an important role in the county’s economy, and Converse County still takes an “all of these above” approach to energy development, “we also really believe renewables are part of the energy portfolio for the country and generally are welcoming to them,” Willox said.

Economically, Willox viewed the solar farm as a good source of tax revenue for the county. “You’ll have sales tax that will be collected during construction, then there will be a property tax value increase,” money from BrightNight that can be used for schools, hospitals, and other public resources in the county, he said.

Still, renewables — much like oil, gas, and coal — are not without “some challenges and some concerns,” Willox said.

A few partnerships between farmers and scientists have shown that some crops react poorly to living under the penumbra of a solar farm. Shade from the panels can sometimes trap too much water near the plants, and the presence of large photovoltaics can make it difficult for farmers to conduct their harvest.

At the public briefing held in Douglas, Wyoming, on Tuesday, county residents gathered in a courthouse basement to hear presentations from BrightNight executives regarding the Dutchman solar farm’s permit application. Afterwards, some county residents voiced concerns regarding the solar farm’s access to transmission lines, its impact on prairie dog migration patterns and the effects of radiation on residents.

BrightNight must wait for its county and state permits before determining its grid access, said Jess Melin, BrightNight’s executive vice president of development. As with other nearby energy projects going through the permitting and contracting phases, Melin said once BrightNight has “a permit and a power contract, that’s the point when they say ‘OK, let’s actually sit down at the table and negotiate queue position,’” for delivering energy to the grid.

Brandon Pollpeter, BrightNight’s director of development, called prairie dog migration a “difficult thing to manage,” and said the company would coordinate with the Wyoming Game and Fish department to consider best practices for responding to the rodents. He added that any high-voltage equipment, which produces a small amount of electromagnetic waves, has been sited far from the community, and would not be a factor to county residents.

“This county is very knowledgeable on energy and energy generation,” said Pollpeter. “We’ve gotten some outstanding feedback.” Pollpeter added that BrightNight increased the project setback and moved its construction entrance in response to local concerns.

There is evidence that agrivoltaic solar farms are just as effective grazing areas as traditional open pastures, and that combining grazing with solar generation increases land productivity by offering crops respite from the sun in hot, arid environments.

In the spring of 2019 and 2020, Chad Higgins and a team of other researchers from Oregon State University tracked sheep grazing at an agrivoltaic solar farm in Oregon, measuring the animals’ growth, grazing habits and water consumption. They split two groups of sheep on the same land; one that grazed near the solar panels, and another browsing on open pastures. What they found led them to conclude that agrivoltaic solar farms can be an ideal setup for sheep ranchers.

“In the early spring grazing time, which is when the most intense grazing is and the most growth is, we could put more sheep on the agrivoltaic array than on the open pasture, and the sheep grew at the same rates,” said Higgins, an associate professor in Oregon State University’s department of biological and ecological engineering. “There was overall more production in that intense grazing period because of the solar panels.”

The reason why has to do with shade. “You can reduce heat stress to plants by watering them more or shading them some,” Higgins said. “If you shade them some — which is what you’re going to do, for example, in a Wyoming project that’s on non-irrigated lands — you’re going to reduce some of that heat stress on those plants. Those plants tend to grow a little more, and as they grow a little more, the sheep take advantage of them.”

The study found that, while the sheep grazing near the solar panels experienced a 38 percent drop in the quantity of grazable vegetation, that was offset by an increase in the available plants’ quality, as measured by the nutritional makeup of the vegetation’s tissue. Despite having access to less vegetation, the sheep grazing near solar panels “were gaining weight at their maximum rate,” and reached similar peak weights to sheep on the open field, Higgins said. “We actually had to fence the sheep in the open field to keep them in the open field, because, given the choice, they all preferred to be in the solar.”

Agrivoltaic solar farms, while suitable for sheep, are more difficult to tailor to cattle, Wyoming’s most common livestock. The state is home to 1.2 million cattle, which are burlier and heavier than sheep. Cows “just beat up equipment by rubbing up against it,” Pollpeter said. The solar industry “is taking a tough look to try and see how that starts to make sense. But, at least in my personal opinion, we’re not quite there yet.”

Among Wyoming’s sheep ranchers, there may be a budding interest in agrivoltaics. “If there are opportunities to make the two work together that provide sheep producers expanded revenue and better financial stability, that’s the type of thing we look for,” said Jim Magagna, a longtime sheep rancher and executive vice president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, the state’s most powerful livestock advocacy organization.

Given the variation in soil, grazing plants, sunlight, moisture, and terrain across Wyoming, Magagna stopped short of endorsing agrivoltaics as the de facto approach to solar farms moving forward. “I think it needs to be a carefully considered decision by the landowner,” he said.

Magagna wouldn’t rule out the possibility of an agrivoltaic solar farm cropping up on public land in the future, a process that would involve years of planning and environmental assessments by the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, as well as stakeholder input. But given the fact that a majority of public lands in Wyoming are grazed by cattle, “I think the opportunity to do that on public land on a very significant scale would not be there today,” he said.

In January, the BLM released an environmental impact statement regarding utility-scale solar farms in 11 Western states, including Wyoming, as it considers whether or not to amend its approach to solar farms in the region. The agency acknowledged agrivolatics as an “emerging [photovoltaic] system” that could gain commercial traction in the future.

Converse County Commissioners expect to finalize their support for the Dutchman project permit during a February 20th vote. The company still needs to secure a permit from the state’s Department of Environmental Quality, whose Industrial Siting Council is already considering the company’s application. Should the state issue it a permit, BrightNight expects to break ground on the Dutchman solar farm as early as March of next year.