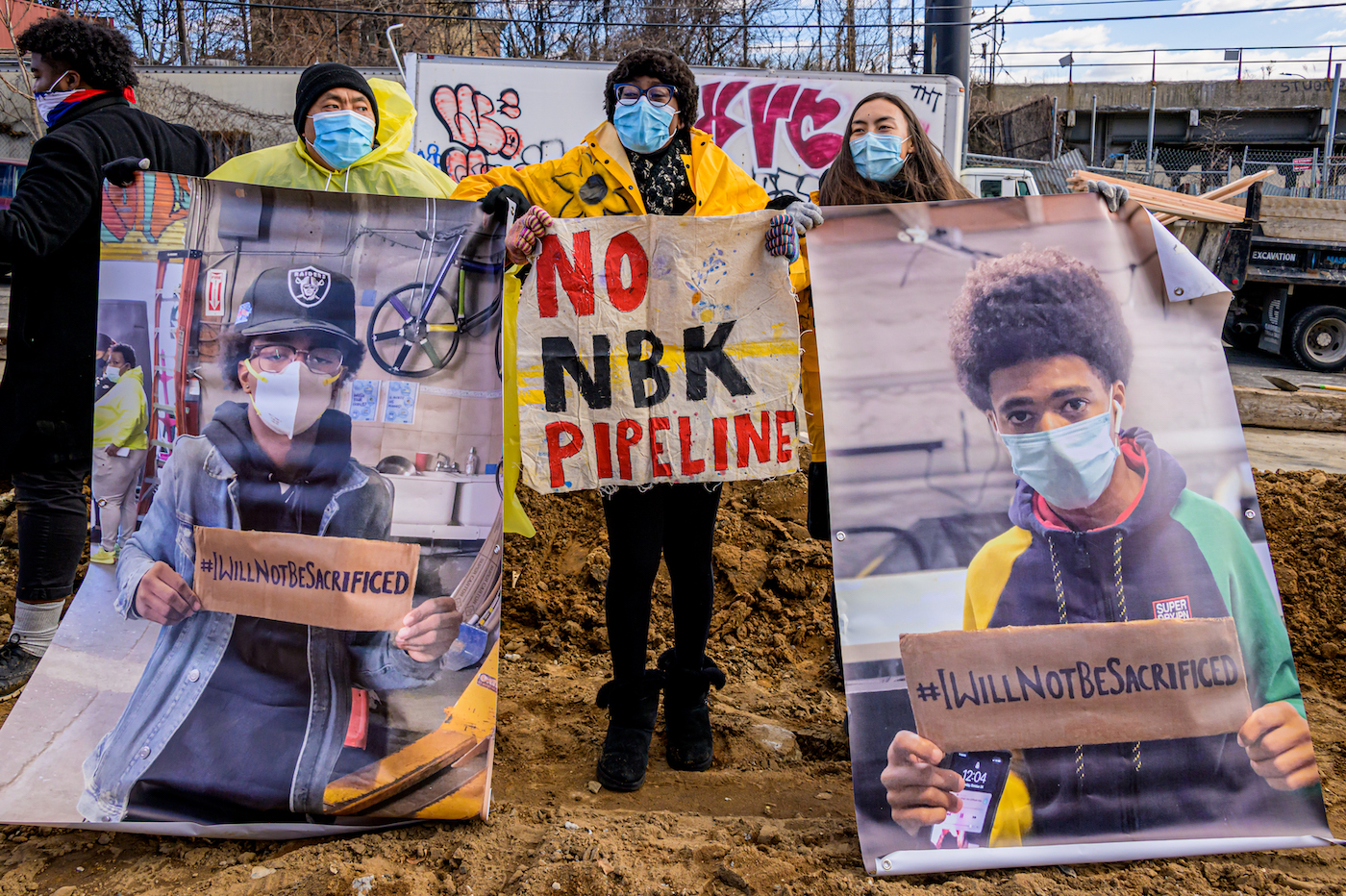

Since early 2020, environmental and social justice activists have staged more than a dozen protests against a 7-mile gas pipeline being built in Brooklyn, New York. They biked the route of the pipeline and told stories about the disproportionately polluted neighborhoods it cut through. Some chained themselves to the site to block construction, leading to 12 arrests last fall. The movement grew to a coalition of 14 organizations, many of them community-based, and earned the vocal support of city council members, state legislators, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, and several of Stringer’s fellow mayoral candidates. Even current Mayor Bill de Blasio has come out against the pipeline.

Now, the heated battle over the Metropolitan Reliability Project, or MRI, which was dubbed the North Brooklyn Pipeline by activists, may be nearing a close. In mid-May, National Grid, the gas utility building it, released a proposal to halt construction of the project.

The proposal outlines which investments the company would be able to pay off and earn a return on through rate hikes to its customers over the next three years. If it is approved by the New York Public Service Commission, which regulates utilities, National Grid would charge natural gas customers $126 million to cover the cost of building the first four sections of the pipeline, which it has completed and are now in service. But it would drop the idea of building a fifth section, at least for now — with an option to bring the project back in the future.

Those terms are a direct response to public opposition to the project, according to a statement in support of the proposal written by the Department of Public Service, the agency responsible for ensuring New Yorkers have access to affordable, safe, and reliable energy. And National Grid’s decision to call off pipeline construction isn’t the only sign that activism influenced the proposal. It includes several other concessions the company would make to satisfy climate and environmental objectives.

But the groups and community members who fought the MRI do not see this as a victory. They are outraged that the proposal still has them paying for a new fossil fuel project underneath their feet at a time when climate science and a prominent state law imply that the use of fossil fuels should be shrinking, not growing.

On June 1, the No North Brooklyn Pipeline coalition launched a gas bill strike, asking opponents of the pipeline to withhold $66 from their gas bills before the New York Public Service Commission, the governor-appointed body that regulates utilities, votes on the proposal. That’s the amount the coalition has estimated the average customer will have to pay for the pipeline over three years if the proposal is approved.

“The hope is that the Public Service Commission will see how incredibly unpopular it is to try to make us pay for this pipeline, and that the community is simply not going to go along with it anymore,” said Lee Ziesche, community engagement coordinator for the Sane Energy Project, one of the groups involved in the coalition.

An unusual rate case

National Grid first proposed raising rates on its Brooklyn and Long Island gas customers in April 2019. Some costs associated with the MRI had already been approved in a previous rate agreement in 2016, and now the company was asking state regulators to raise rates again to complete the pipeline and pay for a number of other projects, programs, and maintenance.

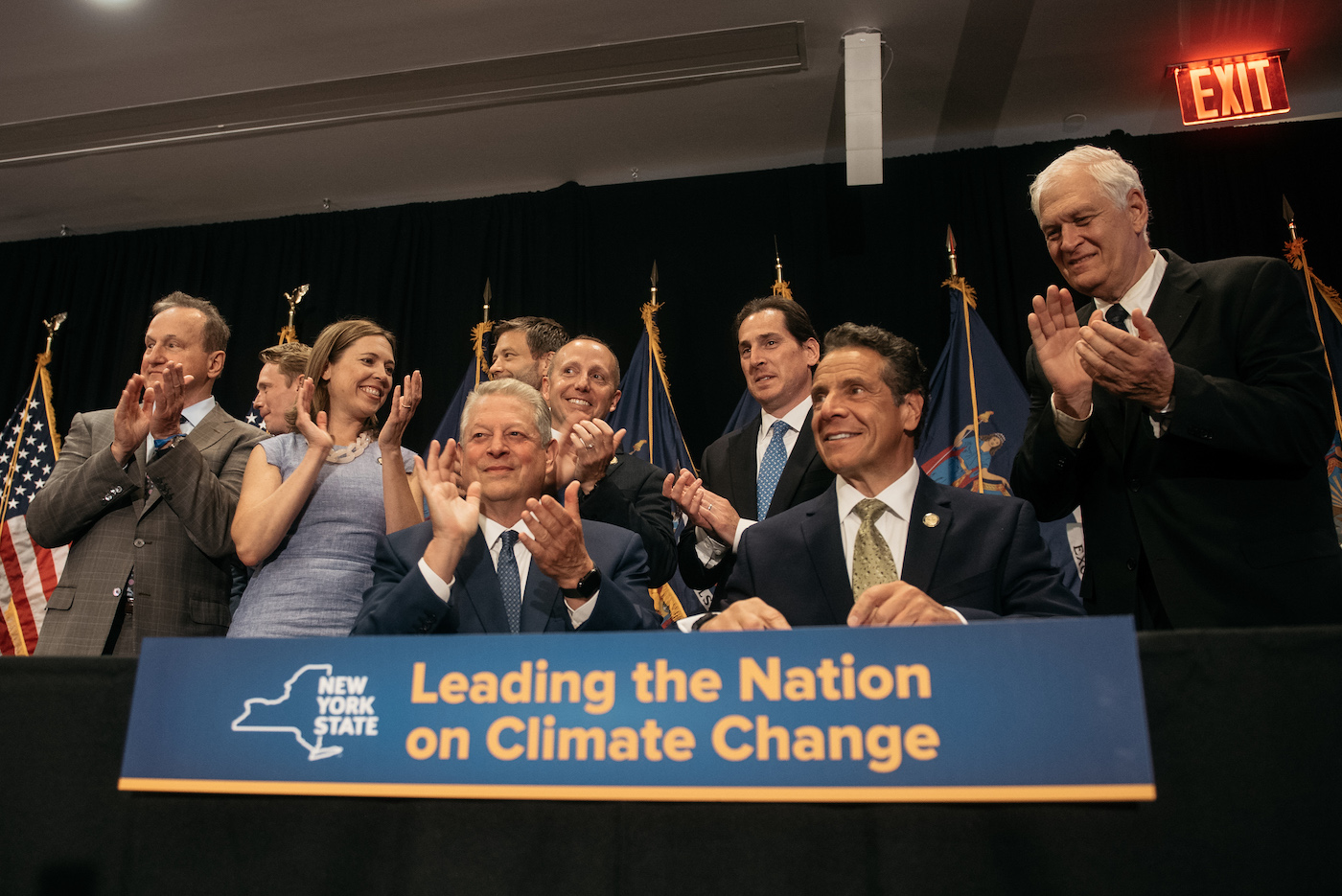

But shortly after National Grid filed its request, New York passed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, or CLCPA, a major climate bill that requires the state to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 85 percent by 2050. Later that year, Governor Andrew Cuomo threatened to revoke National Grid’s license after the company claimed it couldn’t serve new customers unless the state approved a major new interstate pipeline.

Those two events, along with the global pandemic that emerged in early 2020, led to a drawn-out proceeding that took place virtually and brought in much more public attention and participation than is typical. People living near the pipeline’s path who had no idea it had been greenlit in 2016 were suddenly at home witnessing its construction and the growing protest movement against it. Ninety individuals and organizations officially joined the rate case to participate in negotiations, compared to 34 in 2016, and it received more than 8,000 public comments.

The proposal released in May was a compromise reached after extensive confidential negotiations between National Grid and the Department of Public Service, environmental groups, unions, industry groups, the city of New York, and nonprofits that represent low-income residents.

But “compromise” belies the fraught process: Several of the parties, including the Sane Energy Project and Comptroller Scott Stringer, walked out of the negotiations in March. They said the process was dragging on while National Grid was already spending millions building the MRI project, money that hadn’t yet been approved.

“At this point sitting at that table is legitimizing a process by which the utility keeps building controversial infrastructure while parties talk behind closed doors for months on end,” Ziesche said in a statement at the time.

The unclear mandate of New York’s climate law

At the heart of this two-year saga is a fundamental disagreement about New York’s climate law. Activist groups like Sane Energy Project, as well as big nonprofits like the Environmental Defense Fund, posit that regulators have a duty under the CLCPA to bring utilities in line with the law’s greenhouse gas emission targets. They cite a section of the law that says that in making decisions, all state agencies must “consider whether such decisions are inconsistent with or will interfere with the attainment of the statewide greenhouse gas emissions limits.”

To them, that means the Department of Public Service should be pushing utilities to reduce demand for natural gas by getting customers to switch to electric appliances that can run on renewable energy — not expanding the gas system. They worry that new fossil fuel infrastructure will become “stranded,” or obsolete, before it’s fully paid off, and that customers will be left on the hook to pay for something that’s no longer benefiting them.

National Grid and the Department of Public Service, on the other hand, argue that it’s not yet clear what New York’s emissions targets mean for natural gas. They cite another section of the law that tasks a government-appointed body, the Climate Action Council, with figuring out how the state should tackle different sources of emissions, including gas in buildings. The Climate Action Council’s conclusions, and any regulations that come out of it, will take several more years to develop.

“On the one hand, doing what we’re doing amounts to a guarantee that we’re going to spend money badly,” said Justin Gundlach, a senior attorney at New York University’s Policy Integrity Institute. “Some fraction of the investments in a given three-year rate case are going to be either stranded or partly stranded.” However, Gundlach said the Public Service Commission is in a tough spot — coordinating the decline of the gas system is deeply complicated, and the state is still in the midst of a process to determine what, exactly, that decline should look like.

Erin Murphy, a lawyer at the Environmental Defense Fund who was involved in the National Grid negotiations, said the proposal put forth last month contains valuable steps in the right direction. For one, the company would stop marketing gas to prospective customers and offering incentives for people to switch their home heating systems from oil to gas, instead informing customers about alternatives to gas heating, like electric heat pumps.

The proposal takes a step toward shrinking the gas system, requiring National Grid to identify a few older sections of its pipeline system where it could offer customers alternatives to gas heating and retire those pipes rather than replace them. The company would also have to submit a report showing how its business model will evolve to support the state’s emissions targets, and conduct a study on the potential impacts of retiring assets early to comply with those targets.

Finally, any capital-intensive projects the company wants to build to meet long-term demand, like the fifth section of the MRI, or a plan to expand the company’s liquified natural gas facility in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, will be subject to additional review by an outside consultant to ensure they are necessary. National Grid will not be able to recover costs for these projects unless it hits certain targets to reduce demand for gas through energy efficiency and electrification programs.

A spokesperson for the Department of Public Service told Grist the proposal balances the agency’s responsibilities to ensure safe, reliable, and affordable service with measures to align the utility with the CLCPA, and pointed to a first-of-its-kind commitment by National Grid to refer new customers seeking natural gas service to heat pump programs run by its competitors, Con Edison and the Long Island Power Authority.

Karen Young, a spokesperson for National Grid, said the proposal represents an important step toward cleaner, lower-emissions energy system. “We are committing to various measures to reduce gas usage and promote awareness of alternative heating options,” she said. Young echoed the Department of Public Service’s assertion that the plan balances priorities of affordability, better service, “and advancing energy policy in downstate New York.”

Why stakeholders say it’s not enough

Despite these trade-offs, so far only five of the parties that participated in the proceeding have come out and officially supported the proposal, compared to more than 20 that oppose it. While the Environmental Defense Fund supports the plan, it does so with many caveats.

“We’re absolutely going to need to see more than this in the years to come,” said Murphy. For one, the company has only agreed to shrink its forecasted growth by 0.5 percent — which just means less expansion, not contraction. “There needs to be a more significant reduction in gas usage. But this is at least a sort of a beginning for the next couple of years to start to orient the company’s planning around that objective of reducing usage.”

A major problem for those who oppose the MRI is that the proposal allows the company to earn a return on the millions of dollars it spent completing the first four phases of the pipeline during the pandemic, when that spending wasn’t yet approved. But that’s only part of it. Ziesche said that National Grid’s proposed spending to expand and extend the life of gas infrastructure dwarfs what it would spend on initiatives to reduce demand. She said she has no confidence that an outside consultant will bring additional scrutiny to the company’s gas expansion proposals, since Department of Public Service staff have already come out in support of many of those potential projects.

It’s not just activists who oppose the proposal. Even New York City officially came out against it, arguing that it is not in the public interest and should be rejected because it “does not demonstrate a clear and rapid transition off fossil fuels.” The city is pushing for stronger demand reduction targets, asserting that National Grid should be more focused on solutions that do not increase the supply of gas flowing into New York.

Last year, Mayor de Blasio proposed a ban on hooking up new buildings to the gas system — a move that many cities in California are making, and one that would certainly change National Grid’s projections of future gas demand. The New York City Council recently introduced a bill that would codify the ban.

The Public Service Commission can vote to adopt or reject National Grid’s proposal in whole, or modify it, and is expected to do so at its monthly session in July or August.