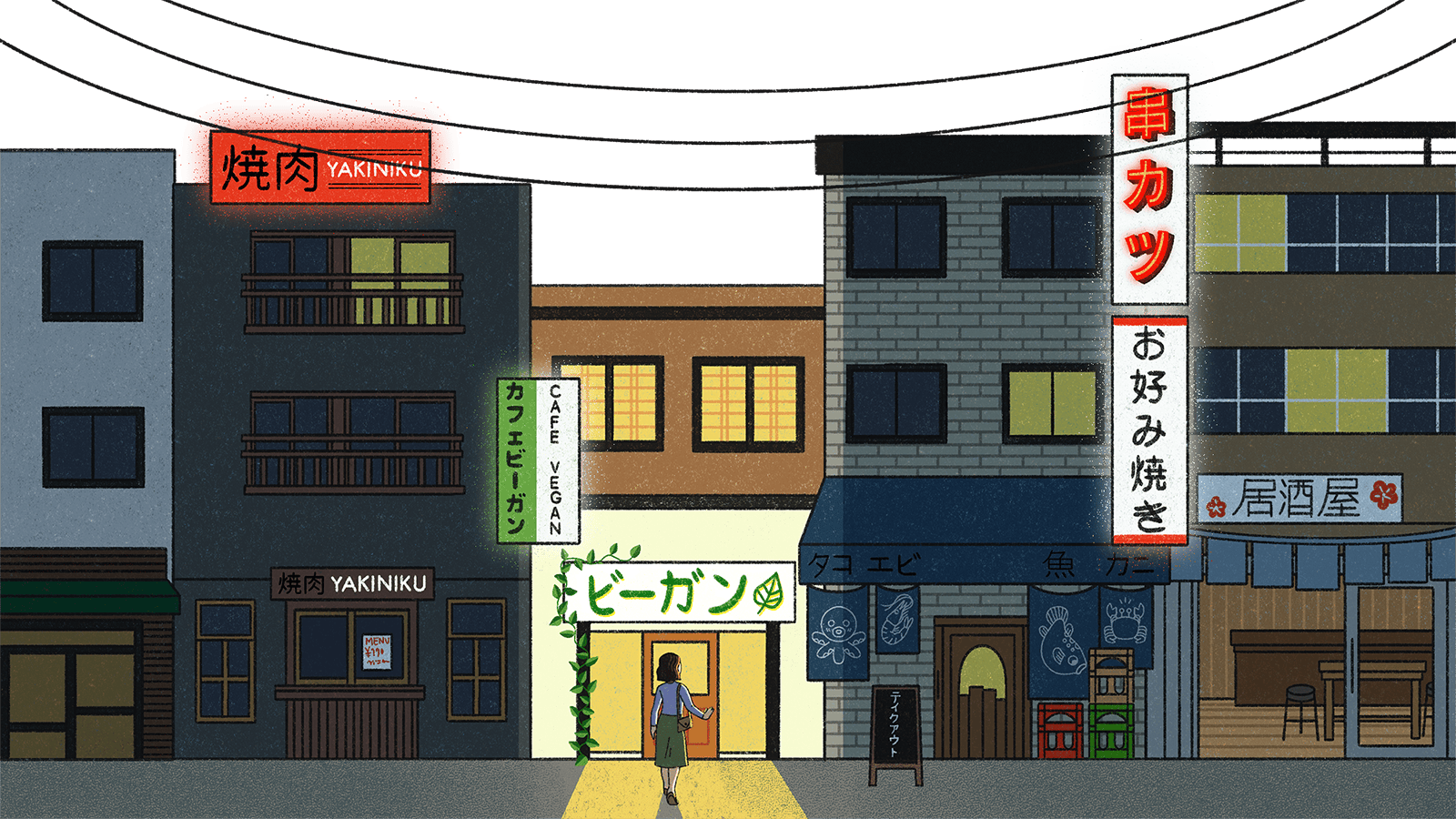

All is quiet at 10:30 a.m. on a Thursday in Shibuya, Tokyo’s famous commercial district. In an alleyway just steps from one of the busiest train stations in the world, a short line of tourists huddles outside of a bar. Finally, half an hour later, the door cracks open and, greeted with a soft irasshaimase, or “welcome,” the parties shuffle in to sample one of the rarest dishes in Japan: vegan sushi.

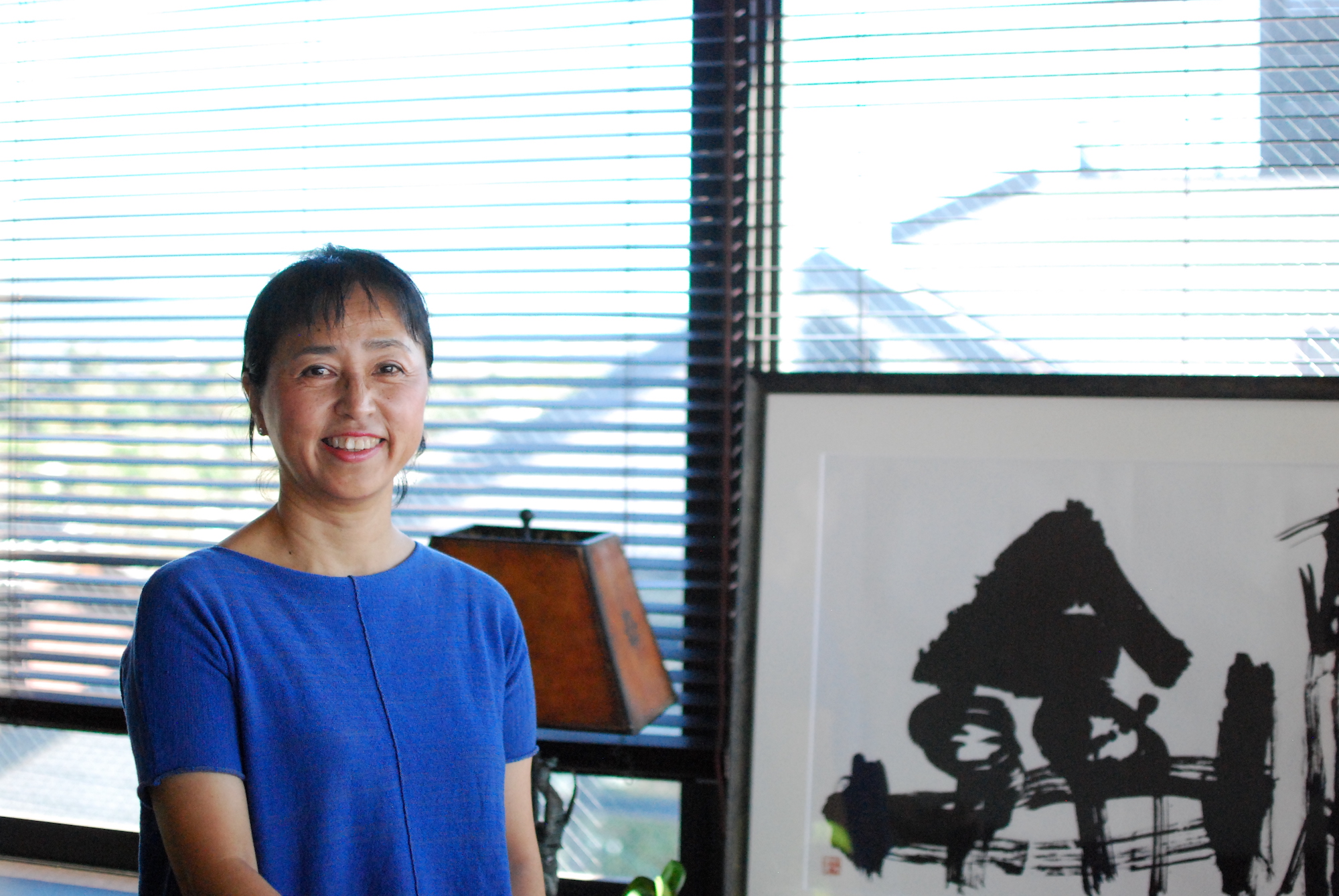

“Nowadays, there are many vegan ‘meat’ products,” says Kazue Maeda, one of the four founding employees of the restaurant, Vegan Sushi Tokyo. “But I’m Japanese. What I really used to love is sushi and salmon.”

Her restaurant attempts to fill a relatively unclaimed niche in the local food scene. Even in Tokyo, where most of the country’s vegan population lives, plant-based versions of traditional Japanese food remain challenging to find — most vegan options are yōshoku, a popular cuisine that puts Japanese twists on Western dishes. Vegan Sushi Tokyo is open only for lunch: Although good reviews keep pouring in, the small business still doesn’t have a storefront of its own, and rents out the interior of a bar by day. It serves 10-piece nigiri lunch sets, which include a plant-based Japanese-style “egg,” “shrimp” tempura, and jewels made out of seaweed that look nearly indistinguishable from salmon roe.

Maeda became a vegan five years ago, due to her growing concern over environmental and animal rights issues. It’s a familiar origin story for those who have come to defy the typical Japanese diet by giving up animal products. “In terms of the vegan movement, I think we’re maybe behind other countries. The number of vegans is very small,” Maeda says. “But there are more and more vegetarian and vegan restaurants in Tokyo, I think because of tourists — especially from countries with many vegetarian people, like Taiwan.”

For all its differences from the United States, Japan’s culinary culture takes after America’s in a key way: It’s heavily meat- and dairy-dependent. Of course, soybean products like tofu are the star of many dishes. But beef, pork, chicken, eggs, or dairy also feature in nearly everything, from high-brow ramen to convenience store rice balls. And then there’s the fish — served raw in sushi and sashimi, grilled as filets, fried in tempura, and present in nearly all other dishes as dashi, a savory broth made of dried tuna flakes and kelp.

Outside large cities, vegan options quickly vanish. In a culture that prizes convention and scrupulous attention to detail, individual accommodations — like vegan menu substitutions — are often frowned upon. And as in many other countries, vegan options are sometimes stigmatized as less nutritious.

But recently, things have been changing. The anticipation of a tourism boom for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo pushed the Japanese government to make more vegan options available in major cities. Restaurants like Maeda’s have begun springing up, offering novel adaptations of traditional dishes. And under pressure from Japan’s pledge to nearly halve its carbon emissions by 2030, the government has begun collaborating with vegan activists and advocates and awarding grants to alternative protein start-ups. Though challenges remain, it’s gotten easier and easier to go vegan in Japan over the last decade.

“Climate issues and animal issues are growing,” Maeda said. “For me, I can’t imagine going back to eating meat again.”

Convincing people to eat less meat is key to reaching international climate goals. Up to 20 percent of planet-warming greenhouse gases come from animal agriculture alone — all the cows, pigs, lambs, chickens, and other animals that people raise for meat, milk, eggs, and the like. According to one study from the University of Oxford that looked at the diets of over 55,000 people, vegans — defined as those who eschew all animal products — create 75 percent less climate pollution than those who eat a meat-heavy diet.

For most of the last two millennia, the Japanese diet was a model of climate-friendly eating due to Buddhist and Shinto objections to meat and dairy consumption. Beginning in 675 A.D., meat-eating was banned by official imperial decree. It wasn’t until 1872, nearly 1,200 years later, that Emperor Meiji lifted the ban, seeking to usher in an era of westernization. Meat consumption grew quickly as domestic beef production boomed and animal products became a symbol of power and status. As reports spread that Emperor Meiji drank milk twice a day, dairy consumption became more popular, too.

Today, Japan ranks 11th in beef consumption globally, and its per capita meat consumption (not including seafood) is 40 percent higher than that of the average Asian country. Japanese people buy eight times more meat than they did in the 1960s, and in 2007, families began eating it more than fish.

Despite this sea change, Japanese people still only eat half as much meat as Americans. And interest in plant-based foods appears to be growing, as it is in Western countries. Japan’s market for plant-based foods tripled between 2015 and 2020, and the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries expects it to double again by 2030. These shifts have taken place as the Japanese population at large has expressed a readiness to shift toward plant-based products for health, animal welfare, and climate-related reasons, according to a 2022 analysis in the Journal of Agricultural Management.

Although no official government statistic exists, a 2021 survey found that 2.2 percent of Japanese people were vegan. This may be higher than the percentage of vegans in the United States, where estimates range from 1 to 4 percent.

But even with the lingering popularity of shojin ryouri, traditional Buddhist vegan cuisine, and even though vegan restaurants have been on the upswing since 2017, Japanese vegans seem to have fewer options than their American counterparts. According to HappyCow, a popular directory of vegan and vegetarian restaurant options, Japan has fewer than four vegetarian restaurants per 100,000 people in Japan, more than a fifth of them in Tokyo. By comparison, there are 19 vegetarian restaurants per 100,000 people in the U.S.

“They don’t realize that adding a small piece of bacon or fish is still meat. I still have to explain it.”

“Even many chefs still don’t know what vegan is, they don’t know the concept,” said Azumi Yamanaka, a vegan activist in Tokyo. She met with Grist at Brown Rice, a sleek vegan restaurant with an organic, health-focused menu near Harajuku, the country’s famous fashion capital. For lunch, she ordered the weekly teishoku special — a set meal that comes with a selection of small seasonal vegetable dishes, rice, and miso soup. “They don’t realize that adding a small piece of bacon or fish is still meat. I still have to explain it.”

When Yamanaka became vegan 16 years ago, she says most people in Japan hadn’t even heard of the term “vegan” — pronounced bi-gan, joining a lexicon of Western loan words that have been integrated into the language with Japanese phonetics, such as ko-hii (coffee) or chi-zu (cheese). But in recent years, she says, being vegan has become somewhat fashionable counterculture — judging from social media trends and an upswing in photogenic vegan cafes, which she says get more young people interested in becoming vegan, too.

“The average Japanese person is interested in beauty but usually has little interest in animal or environmental issues,” she said. Yamanaka herself is an embodiment of a stylish urbanite — with bright blue hair and strappy high heels, which she wears even while pushing a road bike studded with artsy stickers.

Even if trendiness plays a role in drawing people to plant-based lifestyles, Yamanaka says Japan’s vegan population is motivated by a variety of issues, including sustainability and animal rights. The country imports between 40 and 60 percent of its meat but depends on domestic factory farming to produce much of its dairy supply, and its animal protection laws have been given low grades by international animal welfare organizations. Other factors include the country’s relatively high rate of lactose intolerance, which some estimate affects the majority of the population. Egg allergies are the country’s most common food allergy, and between 2010 and 2019, the prevalence of allergies to eggs and milk — along with peanuts and wheat — nearly doubled among Japanese kids.

For over a decade, Yamanaka has centered her life around freelance advocacy, meeting with members of parliament, speaking to government panels, and consulting on plant-based food options for large companies. In 2024, she won an award in the animal rights category at the Japan Vegan Awards, which were launched by a marketing association for plant-based businesses in 2018. Yamanaka says city governments and companies don’t care about expanding vegan options until they want to market to tourists. “They believe vegan products won’t sell, aren’t understood, or have failed in the past,” she said. “Many consider them only for foreign visitors.”

Tourism is certainly a huge economic factor in Japan. In 2024, 33 million foreign tourists entered the country between January and November, outstripping the previous full-year record by 1.5 million. Over a quarter of these tourists hail from neighboring Asian countries with large vegan and vegetarian populations, like Taiwan, China, and Singapore, due to the widespread practice of Buddhism.

“Before 2019, the vegan environment was not so good,” said Mayumi Muroya, chair of the Vegan Society of Japan, the largest vegan and plant-based industry organization in Japan. “The reality is that many of the foreigners visiting Japan are vegans and vegetarians. And with the Olympics coming up in 2020, the government knew the number of visitors was going to increase hugely.” In the run-up to the games — which ultimately took place a year late and without crowds because of the COVID-19 pandemic — the Japanese government created food guidelines to help restaurants offer more vegan options and distributed subsidies to help them pay for those options.

In December 2023, Muroya’s organization became the first ever permitted by the government’s Japanese Agricultural Standards to officially certify vegan products. Adoption requires in-person inspections, and fewer than 10 businesses have been certified. A different nonprofit, VegeProject Japan, started unofficially certifying products as vegan in 2016, and its marker has become the most widely used vegan label in Japan — showing up on instant curry pouches, protein bars, and some cosmetics. Recently, in an effort to make dining easier for tourists, Tokyo began offering subsidies to vegan businesses with foreign language menus available that want to be certified with one of these labels — the Vegan Society of Japan’s certification costs roughly $1,000.

Two hours away by bullet train, the country’s beloved and beleaguered tourism hub of Kyoto has also begun investing money into making the city’s vegan options more visible — both to accommodate foreign visitors and due to the city’s pledge to meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. These 17 global goals were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 to end poverty, address inequality, and protect the planet, prioritizing progress for the countries that are farthest behind. Japan has used them as the basis for a public awareness campaign on climate change, conservation, and sustainability.

Despite its small stature, Kyoto has long been considered an easier place to be vegan than the rest of the country. As both the ancient former capital and a youthful university town, the city is awash with historic businesses maintaining the traditions of a preindustrial Japan and a distinctly crunchy-granola youth culture. Although the population is a tenth of the size of Tokyo’s, it has half as many vegan options. And recently, the local government partnered with Kyoto Vegan, an environmental organization founded in 2020 to expand and increase awareness of vegan options in the city. The seeds of the group began four years earlier, when local vegan advocate Chisayo Tamaki helped a group of tourists find a local izakaya with vegan options on the menu. (They settled for chilled tomatoes and tofu.) She started building a map to make it easier next time.

“Finally, after 2020, the city asked if they could collaborate with me,” she said. Kyoto Vegan receives most of its funding from a grant subsidy from the country’s national tourism agency but is also supported by the city as one of its “Do You Kyoto 2050” projects. The initiative aims to cut carbon emissions down to zero by 2050 — the first government in Japan to set such a target. “They can’t achieve that goal without the support of vegan lifestyles,” said Tamaki. She is also a member of the city’s sustainability working group and has contributed to a slick city-funded magazine project on climate-friendly lifestyles.

In its plan to reduce its carbon footprint, Kyoto considers veganism to be the 11th most effective way to cut down its emissions, below expanding electric vehicles and above teleworking. To meet its goals, the city government is also collaborating with the Plant Based Lifestyle Lab, an initiative backed by a group of private companies to promote and research plant-based foods technologies. Last year, a well-known ramen chain, Ippudo, launched a vegan menu option in collaboration with one of these member companies, Fuji Oil.

“That’s why there are a lot of vegetarian and vegan products on the market these days. Because the government is asking companies to make them,” says Tamaki. For her, it’s a welcome change from just a few years ago when she was told vegans were wagamama, a Japanese word that translates to “demanding” or “picky.”

In many ways, people in Japan face the same barriers to veganism as anywhere else. There are the logistical limitations — the lack of options on restaurant menus and at grocery stores. But there are also the psychological ones, like the stigma of being considered a wagamama, exclusion from social activities, and misinformation about health and nutrition. In 2021, well-known business mogul Takufumi Horie went viral for tweeting “I think veganism is seriously bad for your health.” (Research shows that well-balanced vegan diets are healthy for most people, as long as they take supplements to provide some vitamins and minerals.)

In 2021, Muroya — the chair of the Vegan Society of Japan — tried introducing monthly vegan lunches at an elementary school near Tokyo, the first attempt of its kind in Japan. Her effort ran into these kinds of barriers, like national school-lunch calcium requirements that promote milk and pushback from parents worried their children wouldn’t get adequate nourishment, despite Muroya working with the school’s nutritionist to design the menu. (An article on BuzzFeed Japan about the controversy echoed the parents’ concerns, questioning “how vegan school lunches are good for the environment” and citing “the risk of missing nutrients.”) Similar backlash has also happened to schools in Western countries that pilot vegan meal programs. Muroya’s program lasted for a year, but she says the school still regularly does “meat-free Mondays.”

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges to being vegan in Japan is the country’s culture of conformity — which considers standing out to be troublesome. “Having a different opinion from everybody else is very controversial. Everybody wants to move together as a community,” Yamanaka said. “Some people fear coming out as vegan at school or work due to potential bullying.” Although she says she hasn’t faced much adversity in recent years, former coworkers pressured her to eat meat. Ijime — a term broadly used to refer to bullying in workplaces and schools — is a persistent and sometimes dangerous problem that the government has tried to address.

Muroya said her dietary preferences became a professional problem at mandatory work events, like end-of-year parties, when caterers wouldn’t accommodate her. “Even when I called in advance to warn the restaurant, I was told ‘I can’t do that for you,” she said. Maeda says she was motivated to find a job at a vegan company after years of limited options at her company cafeteria.

Nowadays, that seems to be changing as more businesses expand vegan options. In 2021, an article in Nippon TV News called it a “vegan revolution” when several local government offices began including plant-based dining accommodations in their buildings’ cafeterias.

For Yamanaka, the best way to make a more sustainable, less meat-intensive Japan is to bridge the gap between vegans and non-vegans. She says that when people discuss various issues that can motivate veganism — like sustainability, factory farming, and allergies — as well as the popularity of veganism among tourists, more local governments and businesses can be convinced to make more options available.

Local plant-based businesses are already making an effort to appeal to as many customers as possible. At Universal Bakes, a cult-favorite plant-based bakery in Tokyo’s trendy Shimokitazawa neighborhood known for its vegan croissants and savory tarts, the ethos is to provide allergen-free food, not necessarily animal-free.

“I want people to understand that vegan food isn’t just for a select few. It’s an inclusive eating style,” Yamanaka said. “Reaching beyond the vegan community is essential for creating a vegan-friendly world.”