In 1942, when Mary Tanaka was 2 years old, the U.S. government arrested her father and took the rest of the Tanaka family from Juneau, Alaska, to the Minidoka prison camp in the desert of south-central Idaho. The United States had just entered World War II. The five members of the family spent the next three years in the sprawling, barbed wire-enclosed camp, where Mary briefly attended nursery school before convincing her mother to keep her in the barracks during the day. In 1945, as World War II drew to a close and after the Supreme Court ruled that detaining “loyal citizens” was unconstitutional, the family reunited in Juneau, and her father re-opened his cafe.

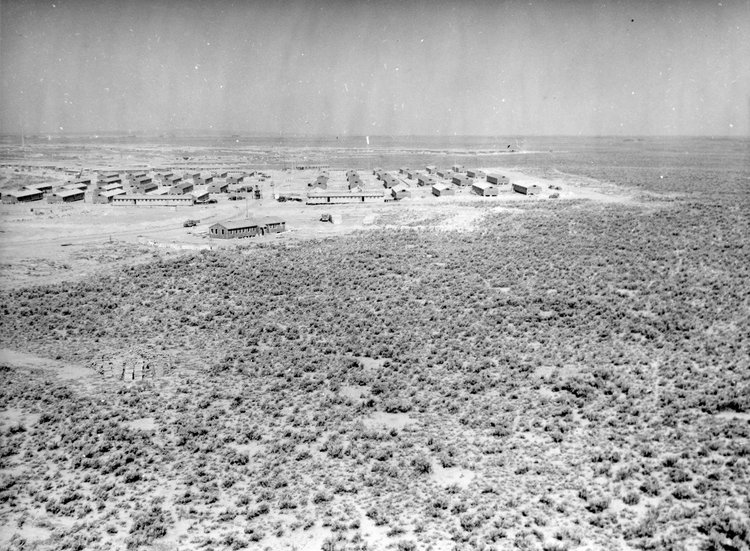

Decades later, Mary (now with the surname Abo) and her older sister Alice Hikido returned to Minidoka, a historic site now managed by the National Park Service. Alice had been reluctant to make the trip, but as the sisters sat on the stoop of the barracks, like they once did as children, she admitted it had been a good, although difficult, visit. They leaned into the wind, sweet with sage, that kicked dust into their eyes and brought memories from the past. “It’s flat as far as you can see,” Mary said. “The only thing you can hear is the wind that whistles. We need that silence.”

Now, the two sisters, Mary’s daughter, and scores of other Japanese Americans with ties to Minidoka fear the quiet and open plains may be broken. Last August, Magic Valley Energy, a subsidiary of the New York-based private equity firm LS Power, proposed building the 1,000-megawatt Lava Ridge Wind Project on 76,000 acres in and around historic Minidoka, mostly public land overseen by the Bureau of Land Management. It’s the second time Minidoka has crossed paths with LS Power, whose plans to construct 400 towering wind turbines would more than double Idaho’s wind energy output.

Lava Ridge is the kind of development that the Biden administration wants to see more of: renewable energy on federal lands. To meet his goal for a carbon-free grid by 2035, President Joe Biden wants to permit 25,000 megawatts of new land-based renewable energy ventures in the next three years. The Bureau of Land Management thinks it’s uniquely positioned to help, and has started a process to make federal land leases cheaper for solar and wind energy developers. But in the high desert of Idaho, these forces have drawn clean energy companies to what Minidoka survivors and their descendants consider sacred ground.

“It’s not just a historic site,” said Robyn Achilles, executive director of Friends of Minidoka, the nonprofit partner of the National Park Service. “This is about people. The site is about respecting and honoring the memory of our friends and family who suffered from this unconstitutional mass incarceration.”

Two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II, the government began imprisoning some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, more than 13,000 of them at Minidoka. Minidoka was one of 10 such prison camps, the locations of which were chosen because they were remote and could be developed for agriculture. More than two-thirds of the imprisoned were American citizens, while many of the others had lived in the U.S. for decades but were denied eligibility for naturalized citizenship. Since there were so many incarcerees — too many to transport by bus — the government placed the camps near railroad lines.

Coming from Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California, many incarcerees found Idaho to be an unfamiliar, punishing land. David Sakura, who was born in western Washington and imprisoned at 7 years old, calls it “America’s Siberia.” While his father was serving with the Military Intelligence Service at Fort Snelling in Minnesota, Sakura was weaving through sagebrush with his mother and little brothers, watching for rattlesnakes as they made their way to picnic in the shade of the looming guard tower. (There were so many rattlesnakes that every year, men made a contest of hunting them down.)

Today, the land surrounding Minidoka attracts wind developers because the same railways that ferried prisoners to Idaho run along transmission lines that can shuttle electricity across western states. And it’s mostly farms and fields — a legacy of the Japanese Americans who cleared, irrigated, and started farming the land.

Dan Sakura, the son of David Sakura and a conservation consultant for the Friends of Minidoka, said southern Idaho is seeing a “wind rush.” According to Sakura, the region, which is managed by the Bureau of Land Management’s Shoshone Field Office, has lax land-use rules, since the region’s management plan hasn’t been updated in 36 years, making it among the oldest in the country. Whereas current plans have guidance for managing visual resources, like striking plants, unique rock formations, and rich colors in soil and rock, there’s no such rules in the old plan. Besides Lava Ridge, Magic Valley Energy recently proposed a second project next door in Twin Falls County, and there’s another underway north of that. The National Park Service estimates that 324 of the 400 proposed wind turbines — each, at up to 740 feet tall, taller than the Washington monument — would be visible from Minidoka’s visitor center, encroaching on almost a third of the view.

This isn’t the first time that the Friends of Minidoka have taken on LS Power. In 2009, the private company wanted to build a transmission line that would have cut right through the national park site. The Friends of Minidoka and the National Park Service fought back, and the line was ultimately rerouted. So last August, when the Bureau of Land Management published its intent to evaluate the wind proposal, the nonprofit was surprised to learn that Magic Valley Energy had come up with a project that they feel threatens Minidoka.

Luke Papez, the project director, said Magic Valley Energy did, in fact, have the Friends of Minidoka in mind when they developed their proposal; that’s why they planned to put the turbines as far as they did from the park. “Since then, we are now understanding that even with that amount of offset, there remains concerns,” Papez said. “We are happy to hear those concerns out and see what can be done.”

In a letter inviting community members to participate in the federal land agency’s public comment period last fall, Wade Vagias, the National Park Service superintendent of Minidoka, said that the facility — with its new roads, substations, and transmission towers — would damage the site’s historical integrity. “The isolated and undeveloped setting was a defining characteristic of the unjust incarceration experience at Minidoka,” he wrote. The project “would fundamentally change the psychological and physical feelings of remoteness and isolation one experiences when visiting Minidoka NHS.”

Dan Sakura and other Minidoka survivors and their descendants have asked the federal government to find a new site for the wind farm. An Interior Department spokesperson said the agency “is reviewing the proposed Lava Ridge Wind Energy project with broad partner and stakeholder engagement that includes Japanese Americans interested in potential impacts to Minidoka, Tribes, and the National Park Service,” referring to tribes including the Shoshone-Bannock, which have said the development would violate their off-reservation treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather.

Sakura said that he and other members of his organization support clean energy. “We’re not like billionaires on Cape Cod that don’t like to look at wind turbines,” he said. He recognizes the pressing threat of climate change, but characterized their fight against Lava Ridge as a matter of protecting their heritage.

When the government began shutting down the camps in 1945, it handed out pamphlets with tips for a “successful relocation,” advising people to avoid gathering in big groups or speaking Japanese in public. “That experience of living in camp made them feel ashamed and less worthy,” said Achilles, whose parents both survived imprisonment. “Those things contributed to how survivors behaved after camp and how they raised their children. So we see it in the second, third, and fourth generations.”

For those who found it too painful to speak about their time in camp, annual pilgrimages to Minidoka offer an opportunity to share memories, seek community, and heal. They think wind turbines would disrupt the solemnity of the site, as well as diminish the park’s educational mission. Minidoka illuminates the fragility of civil rights and an ugly chapter of racism in U.S. history — a lesson as relevant as ever, they say, amid rising reports of hate crimes against Asian Americans. Eighty years since it was built, Minidoka remains isolated. Dwarfed by vast desert and distant mountains, visitors get a glimpse of what it might have been like to be imprisoned there.

Papez said that Magic Valley Energy is eager to find a collaborative solution. “We do not want to have a project that devalues, in any way, the importance of that site,” he said. “We do feel that there’s a solution here that can respect the Japanese American community’s connection to Minidoka that still allows for this important renewable energy facility to be able to make its contributions going forward.”

Magic Valley Energy has already moved the wind farm’s location before: Two potential sites were dismissed largely because they’re important habitats for the declining greater sage-grouse.

The Bureau of Land Management is currently putting together its environmental impact statement, the draft of which is expected this summer. In the fall, the agency plans to release the final version, with a decision to follow soon after. It could approve or deny Magic Valley Energy’s proposal, or offer an alternative arrangement, like one farther from Minidoka, with fewer or shorter turbines.

To David Sakura, the wind project is much too close. One of the turbines would stand about a mile from his old barracks, 15-8-E. To this day, he remembers the address; children committed them to memory so they wouldn’t get lost in the maze of buildings.

“Minidoka is a sacred place where our spirits come back and speak to us,” Sakura said. “We would like to preserve that and make sure that our children, our children’s children, and our great-grandchildren will be able to speak with the spirits that are left behind in Minidoka.”