In Beaumont, Texas, working at one of Exxon Mobil’s plants has long been a way to earn steady wages and support a family in this industrial corner of the Gulf Coast. “We take care of more than just our immediate family,” said Darrell Kyle, the president of the local United Steelworkers chapter, the union representing workers at the plants. “We’re the uncles and aunts,” he said, who help “the struggling nieces or nephews who need a couple hundred dollars to get by, to pay a bill.”

But for the past nine months, about 600 union employees at Exxon’s refinery and other plants have been struggling to pay their own bills: They have been locked out of their jobs because Exxon has been unable to come to an agreement with the union over a new contract. Kyle said that the company is refusing to honor protections for senior workers that have been in place for decades, while the union is demanding that those protections remain in place. At the end of last April, without a contract finalized and with the threat of a union strike pending, the company began escorting employees out of the complex, the Beaumont Enterprise, a local newspaper, reported. The company stated that the provisions the union was asking for were “items that would significantly increase costs and limit the company’s ability to safely and efficiently operate.”

Some workers, willing to take the deal Exxon was offering, began a campaign to decertify the union, which would end union representation at the plants. The United Steelworkers union believes that Exxon illegally assisted the campaign and has filed complaints with the National Labor Review Board.

But in addition to using this legal channel to try to protect their union, the Steelworkers tried a different tactic. They started their own campaign to pressure Exxon into a deal — by undermining the company’s push for public money to build a $100 billion carbon capture hub in nearby Houston.

Last April, just before the lockout began, Exxon announced a proposal to turn the Houston Ship Channel into a carbon capture and storage “innovation zone.” The Ship Channel is a 50-mile stretch in the Port of Houston that’s home to a high concentration of industrial facilities. Exxon said it wanted to work with other companies in the area to capture carbon dioxide emissions from the manufacturing, chemical, and power plants there, and pipe the CO2 out to the Gulf of Mexico to be pumped thousands of feet under the seafloor for permanent storage. It estimates the project could eventually capture 100 million metric tons of carbon annually by 2040, which is about 1.5 percent of current U.S. emissions. Exxon has stressed that the $100 billion concept would require a mix of public and private funding, such as corporate tax breaks, and began lobbying local leaders for support.

In May, the Harris County Commissioners Court, which runs county-level government, budgets, and taxes in the Houston area, passed a resolution praising Exxon’s plan. “Be it resolved that Harris County Commissioners Court hereby commends Exxon Mobil’s commitment to innovation in Harris County,” it reads. Houston Mayor Sylvestor Turner has also been a vocal proponent. In September, when Exxon announced that 10 other companies had agreed to begin discussing the carbon capture hub, Turner was quoted in Exxon’s press release saying, “It’s exciting to see so many companies have already come together to talk about making Houston the world leader in carbon capture and storage. We’re reimagining what it means to be the energy capital of the world.”

The United Steelworkers and other unions that represent fossil fuel workers in Texas are big supporters of carbon capture. To them, it’s a win-win solution to reduce emissions while protecting their jobs in carbon-intensive industries, and constructing and managing all the new required equipment and pipelines would create new jobs. But if workers at Exxon plants are being left behind today, how can they trust the company to bring them along in the future?

“There may be a better company to partner with that actually values their employees and has a good working relationship with the unions,” said Brian Gross, international representative for the United Steelworkers. “We would rather see the city go with somebody like that than somebody that just because they don’t get their way at the bargaining table, locks out 650 families.”

When Beaumont workers caught wind of the Harris County Commissioners Court’s praise for Exxon, they started challenging the uncritical support for the company. In November, a group of union members and supporters showed up unannounced at a commissioners meeting and warned the elected officials not to give Exxon a cent for its plan unless the company changed its tune in Beaumont.

“I am here to oppose Exxon getting special treatment or taxpayer incentives from Harris County for carbon capture projects,” said Paul Harper, one of the workers from Beaumont affected by the lockout. “We are asking the Harris County judge and county commissioners to stand with working people and demand that Exxon Mobil end the lockout that has devastated more than 600 Gulf Coast families.”

Gross told Grist the union members later had additional meetings with Commissioner Adrian Garcia, who had introduced the resolution supporting Exxon’s carbon capture plan, and Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, the head of the commissioners court, about the issue. They also started a petition pressuring the commissioners to hold Exxon to a higher standard.

The commissioners appeared to take the message seriously. In December, Hidalgo, Garcia, and Rodney Ellis — the three commissioners who had approved the resolution celebrating Exxon’s plan in May — sent letters to Exxon CEO Darren Woods urging him to end the Beaumont lockout. “While in May we commended your commitment towards mitigating the effects of carbon, we are writing today to inform you that our offices will prioritize policy collaboration with entities that can demonstrate respectful, worker-centered labor relations,” the letters said.

In an emailed response to Grist’s questions about his letter, Garcia wrote that he had sent it due to the need to “balance competing interests” and said that carbon capture technology will be necessary to address climate change.

In an emailed statement, Exxon did not respond to any of Grist’s questions about its carbon capture initiative or the letters the commissioners sent.

It’s unclear whether Exxon’s vision for a carbon capture hub in Houston would pan out even with generous local tax breaks. Fossil fuel companies have been advertising their efforts to research and develop carbon capture technology for decades, but so far they have only found a way to make the economics work in limited cases like natural gas processing and ethanol refining. These kinds of facilities emit a purer stream of CO2 that’s easier to capture, unlike the cocktail of pollutants that come out of a power plant, for example. Most of the existing facilities that capture carbon make it work by selling the carbon dioxide to oil companies, which inject it into aging oil wells to stimulate additional oil production — a practice that doesn’t necessarily lower overall emissions.

But the economic and political landscape for carbon capture is changing. The bipartisan infrastructure bill that President Joe Biden signed in November included a raft of policies and funding to support the development of carbon capture, including $3.5 billion for demonstration projects, a new finance mechanism to fund the construction of carbon dioxide pipelines, and millions to fund permitting of underground CO2 injection wells. A coalition of carbon capture proponents are fighting for more provisions to be included in the Build Back Better Act, which is currently stuck in the Senate. They want the legislation to increase the value of existing federal tax credits for carbon capture and lower the barriers to claiming them. Exxon also recently announced that it would target reducing the emissions from its operations to net-zero by 2050, responding to immense pressure from shareholders for a more ambitious climate plan.

However, another obstacle for the proposed carbon capture hub may be community members affected by pollution from the plants in Houston. Corey Williams, research director for Air Alliance Houston, a nonprofit advocacy organization, told Grist via email that there has been “little, if any” discussion on what the carbon capture hub will mean for toxic emissions or safety issues, like explosions and chemical releases, that threaten communities near the industrial facilities in the Houston Ship Channel. Can carbon capture mitigate some of those emissions, too? Or would the increased energy demand to run the carbon capture systems increase pollution?

“I don’t know the answer, but it should be answered before these projects move forward,” Williams said. He added that he would rather see companies taxed for their carbon emissions than incentivized with tax credits to continue carbon-intensive activities.

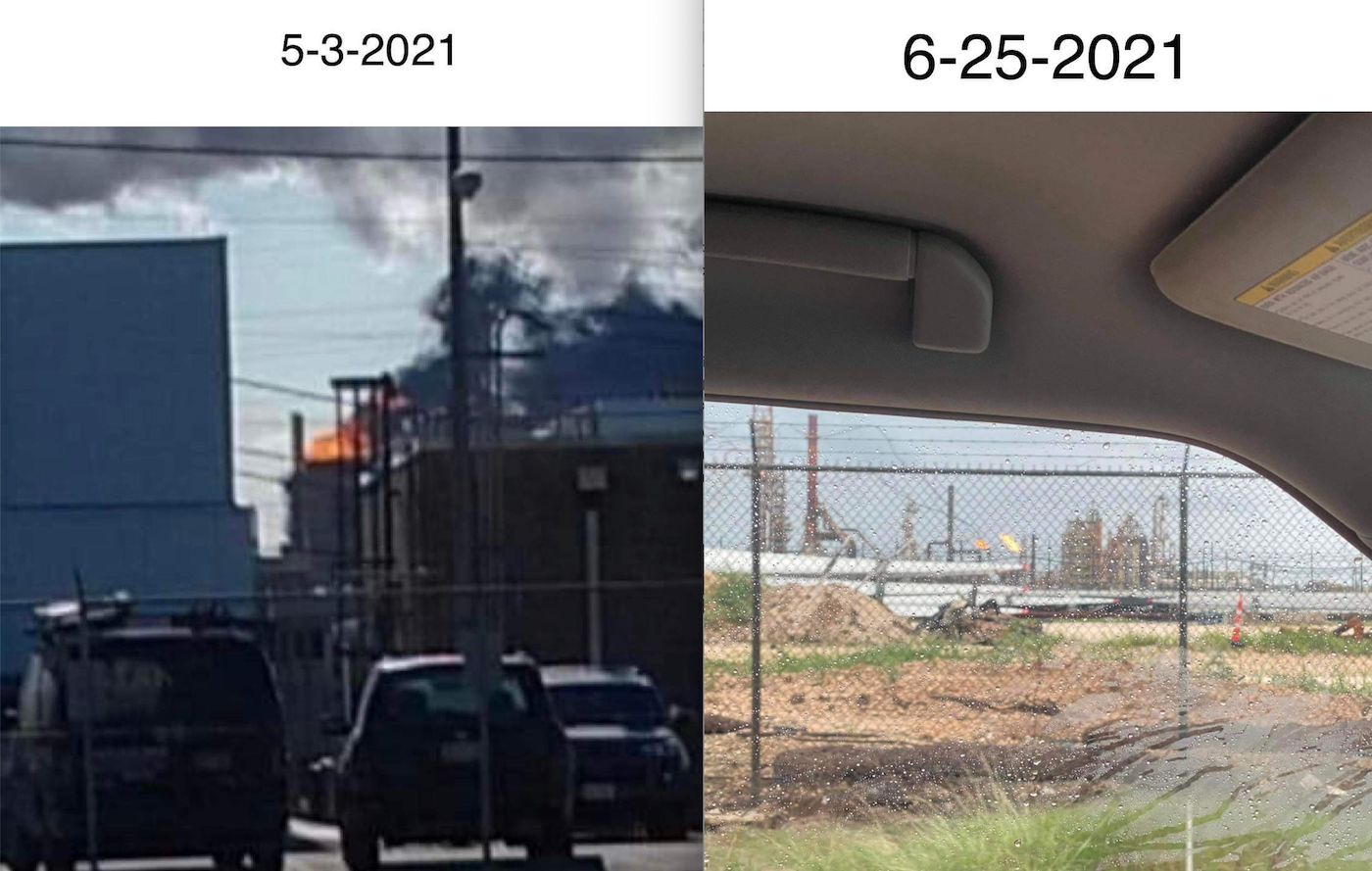

As the Beaumont lockout goes on, the United Steelworkers are not only worried about their jobs. Exxon has replaced the skilled union members with temporary workers, and Kyle is concerned about the safety of the surrounding community. He said he and his fellow union members have regularly seen emergency flares at the chemical plant, which typically means the plant is experiencing some sort of issue. In order to stave off a bigger problem, workers have to release and burn certain gases to regulate the pressure inside the plant. “Damn near every weekend, most nights, there is some kind of flaring going off — and the refinery is only running at 60 percent capacity,” he said. The pollution that spews out from those flares — toxins like benzene and nitrogen oxide — falls on a predominantly Black community in the shadow of the plants.

But Exxon has not been reporting those flaring events to Texas regulators. According to a review of emissions reports Exxon filed with the Texas Commission of Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, over the last nine months, the company only reported two small flaring events in May and July to the state agency. Prior to the lockout, it was reporting approximately one event a month.

In response to detailed questions from Grist about the apparent discrepancy, a TCEQ spokesperson stated that reporting requirements “do not apply to all instances of flaring.” ”In some cases, steam can also be visible from flares and other plant equipment and may look like white smoke even though it’s not,’ the spokesperson said.

In December, workers voted on whether or not to decertify the union, but the votes were impounded by the National Labor Relations Board while it investigates the union’s accusations of coercion by Exxon. In one video posted to the company’s site, Exxon said that removing union representation would end the lockout — a promise that the union said amounts to an effort to improperly influence the vote. The Steelworkers also accuse the company of refusing to bargain and bargaining in bad faith. In a statement, the company refuted those claims. It also said it continues to operate the chemical plant safely.

Until Exxon and the union can agree on a contract, plant workers will remain out of a job, and out of a paycheck. These days, Kyle’s coworkers — who had been working for a company that reported nearly $7 billion in profit in just three months last year — are getting by with temporary jobs, cash donations from the union, and weekly visits to the food pantry it set up for locked out workers.

“All the other USW locals around the world have been donating money to keep that grocery store up, and enable us to give gift cards to help people out,” Kyle said. Meanwhile, he said, Exxon has, “trillions of dollars, and all they talk about is, ‘Hey, we gotta save money, we have to save money.’”