This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

Millions of years before dinosaurs went extinct, what is now Utah was submerged by a broad, shallow sea. Over millennia, as the water receded and tectonic plates shifted, rich organic marine material accumulated, forming thick layers of sediment that eventually became the fossil fuel deposits of the Uinta Basin in the northeastern part of the state. The formation is estimated to hold as many as 300 billion barrels of oil — more than the proven oil reserves of Saudi Arabia.

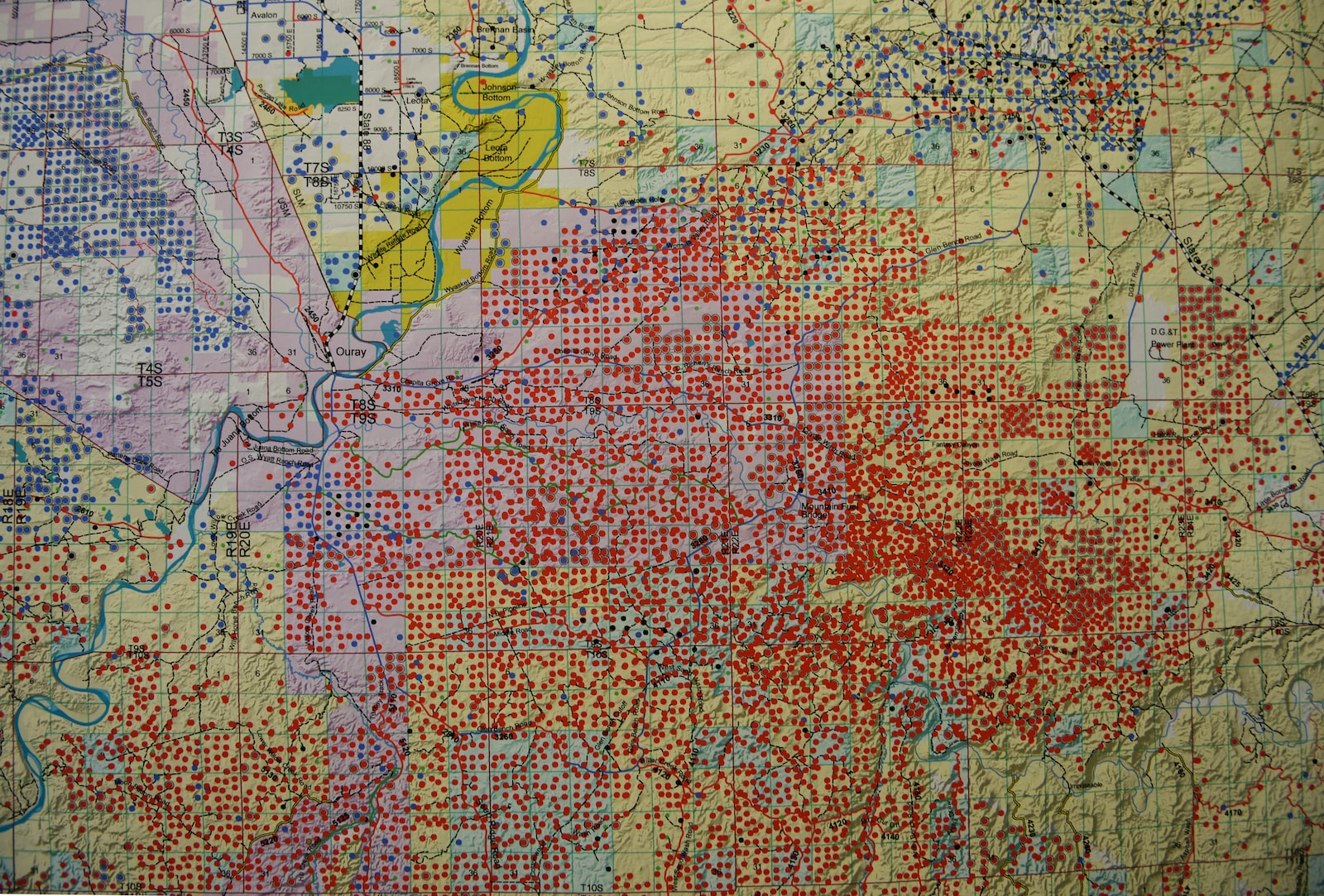

The basin’s immense oil-producing potential remains largely untapped. Drillers in the Uinta Basin extract about 65,000 barrels of oil per day, or just over 1 percent of the more than 5 million barrels drilled daily in the Permian Basin, which straddles West Texas and New Mexico and is the country’s most productive fossil fuel reserve. One of the biggest hurdles is the waxy and viscous quality of Uinta oil, which is so thick that it needs to be constantly heated to keep it liquid. The deposits are also trapped in tiny pores between rocks and more widely dispersed than other shale formations in the country. As a result, oil drillers have been tepid in exploring the basin, despite high gas prices and calls to boost American oil production.

A state-owned company from the tiny Baltic nation of Estonia wants to change that. The company, Enefit American Oil, has proposed strip-mining 28 million tons of rock, heating them up to temperatures around 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and extracting a type of synthetic crude oil. Enefit plans to operate on about 7,000 acres of desert land just south of Dinosaur National Monument and produce 50,000 barrels of oil per day, almost doubling the entire basin’s production. Its novel oil extraction method is also reportedly up to 75 percent more carbon-intensive than traditional fossil fuel extraction. No operation of its kind currently exists in the United States.

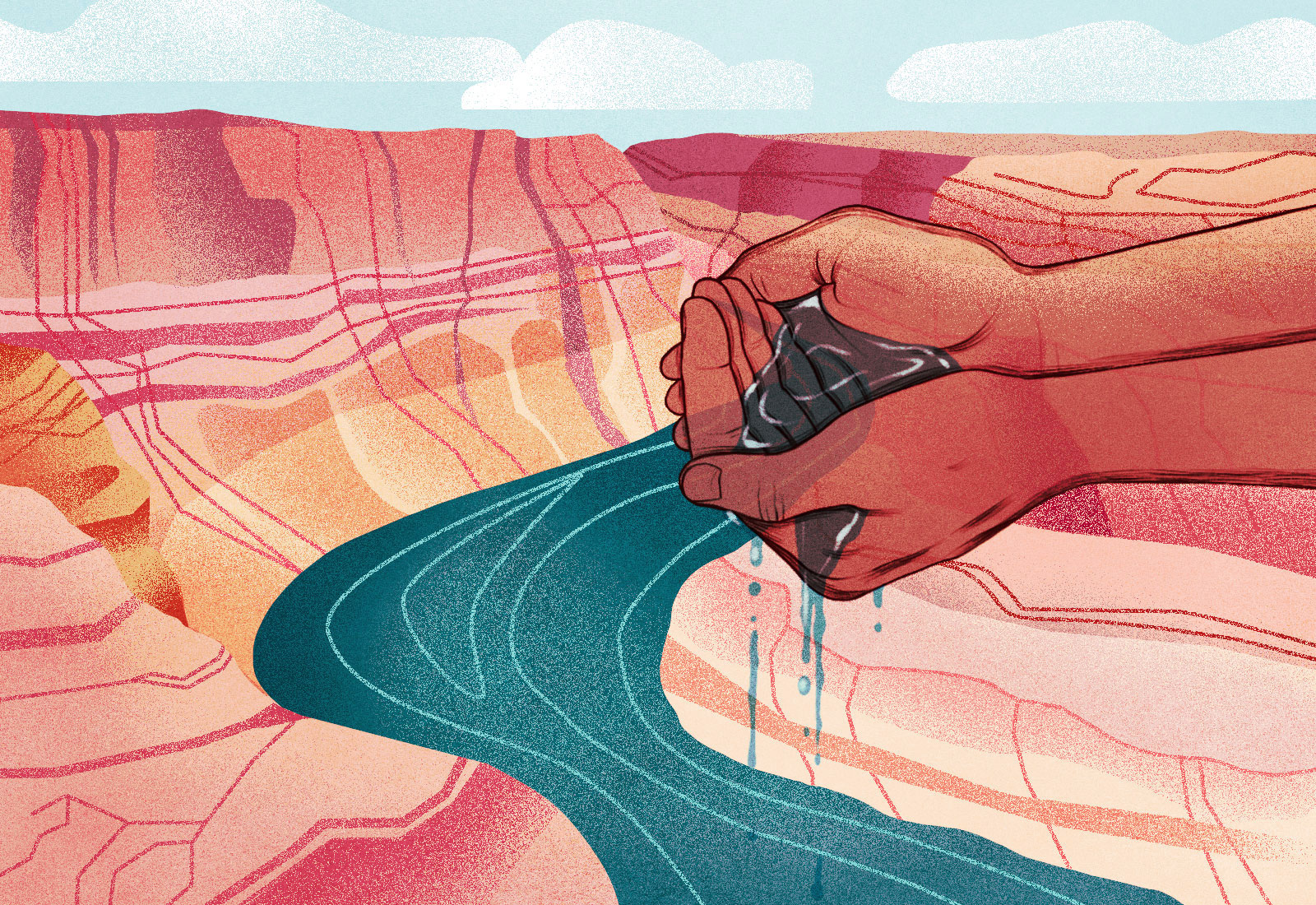

But Enefit’s grand plans hinge on one crucial resource that’s in short supply all over the American West: water. The operation needs millions of gallons a day to break up the petroleum-carrying rock and extract oil. In 2011, the company purchased a water right for approximately 10,000 acre-feet — or 3.2 billion gallons — of water from the White River, a tributary of the Green River which flows into the beleaguered Colorado River.

Utah and six other Western states are overwhelmingly dependent on the Colorado for their needs, from urban drinking water to agriculture. But a yearslong megadrought fueled by climate change has left the river in dire straits, and states hold more water rights on paper than physically exist in the river. As a result, water users are making painful cuts to prevent the river’s reservoirs from reaching dangerously low levels. Historically, Utah has not used its full allotment from the river and has restricted large new appropriations for decades in order to fulfill its obligations to Native tribes and downstream states.

A complex set of rules govern the ownership and use of water in the Colorado River basin. Key among them is the “use it or lose it” principle, which dictates that a water right once appropriated must be put to “beneficial use” — such as for farming or mining — within a specific amount of time. Utah law requires that this threshold be met within 50 years, which is where Enefit ran into trouble. The water right that the company purchased in 2011 dated back to 1965 — meaning it was due to lapse in 2015. If Enefit didn’t put it to use by then, the water right would return to the state. Given the number or regulatory hurdles it needed to overcome before it could even start drilling, there was no way it would start using its water in time to keep its right.

State laws allow one exception to the 50-year rule: Public water suppliers and electrical cooperatives may apply for a 10-year extension to prove the water has been put to use. The logic is that it’s OK to hoard water rights only if it means preserving reliable water and electricity access for Utah residents.

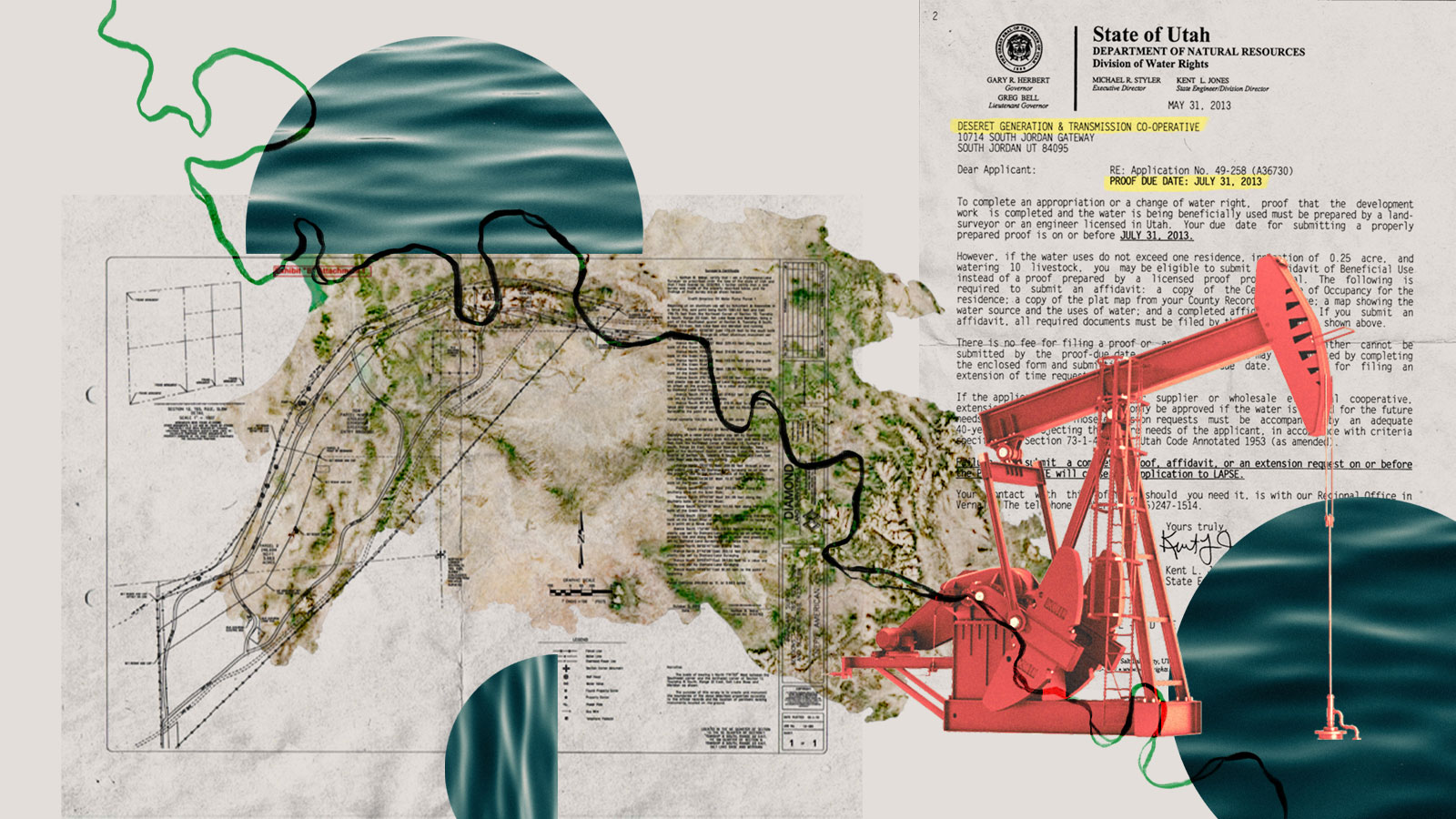

How Enefit could claim to be promoting either of these goals is unclear. Nevertheless, the company found a way to capitalize on the loophole. With the deadline looming, Enefit transferred its water right to Deseret Generation and Transmission Cooperative, a public utility serving about 45,000 customers in northeastern Utah. The price? Just $10 for all 3.2 billion gallons. Deseret then turned around and leased the water right back to Enefit, granting it the 10-year extension it needed.

The extension application requires public entities to prove that the exception they’re requesting “is needed to meet the reasonable future requirements of the public.” An electric cooperative holding on to a water right at the behest of an oil mining company does not appear to be in line with the letter or spirit of the law, given that Deseret produces its electricity from coal shipped in from a mine in Colorado.

Michael Toll, an attorney with the conservation nonprofit Grand Canyon Trust, called the move “completely unlawful” and said that it “undermines the legislature’s intent in carving out that narrow exception to the 50-year deadline.” The Grand Canyon Trust has been protesting the water right transfer with the state water rights agency and litigating Enefit’s project in federal court. The Trust and a coalition of environmental groups argue that the water right should’ve been forfeited and returned to the state.

Jeff Peterson, a representative for Deseret Power, did not respond to specific questions about the Trust’s allegations but referenced a legal filing submitted to the Utah Division of Water Rights, in which the cooperative questioned the Trust’s standing to file an administrative protest and stated that its “legal assertions are contrary to Utah law.” The cooperative plans to build additional electricity generation units, according to the filing, and the water right in question “will play an important role in Deseret Power’s continued operation of the Bonanza Plant and its ability to meet the reasonable future electricity needs of the public.”

The stakes are high: If Enefit’s project moves forward, it is likely to worsen air quality in a region that is already one of the most polluted in the country, thanks to its mountainous topography and intensive drilling that’s already happening there. The basin is routinely out of compliance with federal smog regulations, and the state public health department has documented spikes in stillbirths in the area.

Even beyond its local effects, Enefit’s plan would be a “climate disaster,” according to Brian Moench, president of the nonprofit Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment. Producing 50,000 new barrels of oil a day for the next 30 years would lock in the annual equivalent of carbon emissions from 63 coal plants at a time when the Biden administration is pushing to cut the nation’s carbon emissions in half by 2030.

“It’s really not an overstatement to say that this project would be one of — if not the — most harmful single industrial project in the history of industrial development on the Colorado Plateau,” Toll concluded.

Enefit’s ambitious plans to mine oil in the desert highlands of Utah depend on the Bonanza power plant in northeastern Utah, which is one of just a handful of coal plants still clinging to life in the American West. The 500-megawatt plant is owned by Deseret Power, sits just a few dozen miles from Enefit’s proposed mining location, burns 2 million tons of coal a year, and is dependent on water from the Green River to generate power. The cooperative has a pipeline that moves water from the Green River to the Bonanza plant. (According to public comments and documents submitted by Enefit and Deseret, the mining company plans to make use of this pipeline and develop its own extensive infrastructure to ferry water to its mining location about 20 miles away.)

Deseret is allowed to draw millions of gallons a day from the river, but for decades it only used a portion of its allocated water right. In particular, one 1959 water right was never put to “beneficial use.” Utah’s 50-year rule meant the right would expire in 2009 and return to the state’s public pool. Not wanting to lose its access, Deseret Power pushed legislation that would allow public water utilities and electric cooperatives a 10-year extension to the water use rule. According to the state legislator who sponsored the bill, the electric cooperative always had plans to construct a second coal unit and the water was needed for the expansion. The bill sailed through the legislature, and after it was signed into law, Deseret received the extension it was seeking.

Deseret made use of the 10-year extension once again in 2013 — but this time to benefit Enefit. After Enefit transferred its 10,000 acre-feet water right to Deseret, the electric cooperative submitted an extension request, again citing its future plans for the Bonanza coal plant. The Uinta Basin was at the height of the fracking boom at the time, and a recent Utah Department of Transportation report projected significant growth in the region. The boom would mean increased demand for electricity both at the fracking sites and as a result of population growth. Deseret claimed that it planned to meet that need with a second coal generation unit in the next 5 to 15 years and a third unit in 15 to 25 years.

“It is anticipated that the operation of each of these generation units will require up to an additional 15 [cubic feet per second] of water, resulting in a total water demand at the Bonanza plant of approximately 45 [cubic feet per second],” the application noted. The state water division approved the request without any fuss.

Almost a decade later, Deseret has not built even that second unit. In fact, in 2015 the company entered into an agreement with the Environmental Protection Agency and green groups to limit its coal consumption to 20 million tons for the rest of its plant’s operational life after 2020. Given that it burns about 2 million tons a year, that would mean the plant is due to shut down around 2030.

Deseret appears to have since leased the water right back to the mining company. In 2016, Enefit responded to the Bureau of Land Management’s environmental review of a new water pipeline the company planned to build from the Bonanza plant to its proposed mining location. In the letter, Enefit revealed that it has “an exclusive contractual right” to use Deseret’s water right. This was the first public indication that Deseret had entered into a contractual agreement with Enefit to lease the oil company its former water right.

The existence of the contract means that the electric cooperative is no longer using its 10-year extension to meet public demand for power, according to Toll, the Grand Canyon Trust attorney.

“Deseret power is not meeting its legal obligation to exercise diligence, because its contract seemingly all but forecloses Deseret Power from using the water itself,” he said. “If it really no longer needs this water to generate electricity to meet the public’s future power demand, then there is no reason that they would even hold on to it in the first place — and the water right would be forfeited if they don’t actually need it for the purpose that they said they were going to use it for.”

It’s unclear exactly how Deseret stands to benefit from the deal. The contract is not public, and both companies declined to comment on the details in the agreement. Attorneys Grist spoke to speculated that Enefit may be paying Deseret for its services, or that the Estonian company may have agreed to purchase power from Deseret when it sets up its mining operation.

In the legal filing filed with the Division of Water Rights, Deseret claims that it still has plans to build a second generation unit and possibly a third. Since the settlement with the EPA does not require it to close the Bonanza by 2030, Deseret noted that it may install additional emissions control technologies or run its existing unit on a seasonal basis, thereby extending the plant’s life beyond 2030.

“Deseret Power is currently evaluating alternative generation options at the Bonanza Plant,” the cooperative noted. “All the additional generation capacity will increase the water demand at the Bonanza Plant.”

Jared Manning, the deputy state engineer with the Utah Division of Water Rights, said that if Deseret lost its water right, the water would most likely not be reappropriated and would remain in the White River. That’s because the state has not been appropriating large new water rights in the Colorado River Basin since 1990.

“We’re not approving large applications in the Colorado River right now,” said Manning. “If this lapsed, we wouldn’t change our policy. We wouldn’t go out and approve some similar size application or anything like that.”

Manning added that, since only municipalities and public utilities can apply for the 10-year extension, his office doesn’t receive many applications requesting additional time to prove a water right has been put to beneficial use. Since the 2008 law allowing extensions was signed into law, Manning said the agency has processed nearly 450 such applications. Deseret has received three such extensions for two different water rights.

With its purchase of Enefit’s right, Deseret now has ownership of a precious and dwindling resource: Almost all waterways in the state have been fully appropriated and, since the state has not been granting large new water rights, the water that is available is typically purchased from another user. Emily Lewis, a former attorney in the Utah Division of Water Rights who is now a water rights attorney and a professor at the University of Utah, said that farmers and industrial water users — like coal plants — are some of the major water holders in the basin, and therefore hold the keys to new water-intensive projects in the area.

“There’s not a lot of water out there these days,” she said. “One of the biggest sources of water that’s going to become available is from retiring coal plants. That’s already happening.”

When Deseret’s 10-year extension expires in 2025, the utility will either have to show the water is being used or apply for another extension. State law requires that Deseret show both that it has a need for the water to produce power and that it has constructed infrastructure to move the water from the river to the plant. It’s unclear how the cooperative will meet these requirements if the coal unit at the plant is expected to shutter in the coming years.

Enefit’s infrastructure plans, which the company has dubbed the “South Project,” have also run into legal trouble. The company plans to build a pipeline and transmission corridor on federal lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM. In 2018, after conducting a years-long environmental assessment, the BLM approved the company’s request for seven rights of way.

The Grand Canyon Trust and a number of other environmental groups that had been following the agency’s deliberations sued in early 2019 to challenge the approvals. They alleged that the BLM had failed to adequately consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service, a federal agency in charge of protecting endangered species, among other shortcomings. The Service had not properly considered the effects of the project on four endangered fish species in the Green River, they argued, and thus BLM’s approval of the rights of way did not comply with the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. A federal court is currently weighing the environmental groups’ arguments.

If the federal court sides with the agencies’ decision and the project moves forward, Moench, the physician, said the effects could be devastating for both the natural landscape and those who live in Vernal, the closest town to the proposed mining location. He pointed to the environmental degradation in Estonia, where Enefit has already been mining. When Enefit finishes mining and processing shale oil, 45 percent of the shale is converted into fine ash, which is deposited in giant piles visible from space. The prospect of such externalities in the Uinta Basin, which already faces a plethora of environmental threats, has hardened Moench’s opposition to the project.

“We have wildfire pollution, dust pollution, particulate pollution, high volatile organic compounds, and high ozone,” Moench said. “Approving the Enefit project would be like pouring gasoline on the fire of an existing pollution nightmare.”

Correction: An earlier version of the story misnamed the Utah Division of Water Rights.