Last fall, the town of Brookline, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, tried to solve a climate change problem that’s been put on the back burner in many state capitals: reducing emissions from fossil fuels burned in buildings. The fuels burned in boilers and furnaces, hot water heaters, and stoves account for nearly a third of the commonwealth’s greenhouse gas footprint. Following the lead of many cities in California, Brookline’s government voted overwhelmingly to pass a law restricting gas hookups in new construction. With some exceptions, the bill would force the installation of electric appliances that produce zero direct emissions.

While Brookline was the first community on the East Coast to try and limit gas systems in new buildings, similar plans were also being hatched in neighboring Cambridge and Newton, and earlier this year, New York City mayor Bill De Blasio expressed interest in a building gas ban. But all new bylaws in Massachusetts have to be reviewed by state attorney general Maura Healey before they can be enacted. In late July, Healey killed Brookline’s bill, finding that it violated state law.

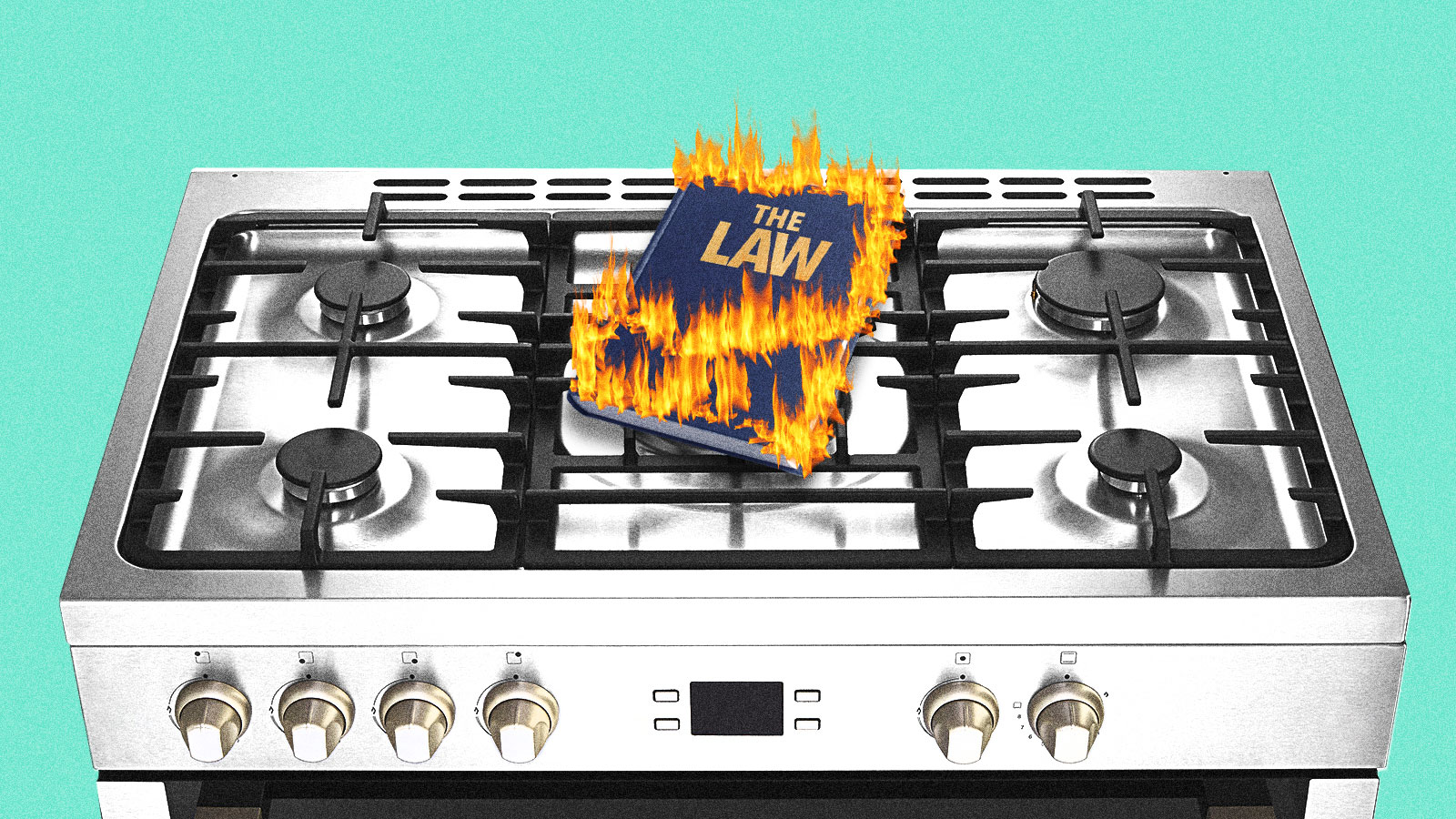

The decision points to an issue that Massachusetts, New York, and California — which, unlike most states, have legally binding targets to reduce their carbon emissions to net-zero — have yet to fully grapple with: outdated policies that favor fossil fuels.

Healey is known to be an advocate for climate action, and she wrote in her decision that she agrees with Brookline’s objective. Nevertheless, she found that Massachusetts towns don’t have the authority to create their own building permitting rules or to control the piping installed in buildings. The bylaw also would have stepped on the toes of the Department of Public Utilities, the state agency that regulates the sale and distribution of natural gas and has a legal duty to ensure customers receive “uniform service” from utilities.

Under Massachusetts’ utility laws, if a potential customer requests gas service, the utility that serves their area must provide it. This common provision in public service law, often referred to as a utility’s “duty to serve” or “obligation to serve,” is meant to guarantee that people have equal access to reliable gas service. Another interpretation might be that it gives citizens the legal right to burn gas in their homes. And for environmental advocates looking to speed up the transition to emissions-free buildings, it’s becoming an obstacle.

“Now that we want to phase out certain kinds of energy service, like natural gas and other fossil fuels — these provisions are going to need to be revisited,” said Amy Turner, an environmental lawyer and fellow at Columbia’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. Turner said that gas companies can “subvert the intention” of these laws to push for increased fossil fuel infrastructure.

That’s already happening in New York, where the “duty to serve” provision is written in a way that seems to promote gas as a way of life. It says that gas is “necessary for the preservation of the health and general welfare and is in the public interest.”

New York utilities have cited their “obligation to serve” to defend spending millions on expansions to the gas system at a time when other state policies are incentivizing customers to reduce consumption or get off gas altogether. In the long term, as the pool of gas customers grows smaller, these investments could lead to exponentially higher rates for the customers who remain, or never be paid off at all.

Earlier this year, Con Edison, a New York electric and gas utility, successfully exploited the state’s “duty to serve” provision when it asked state regulators for permission to raise customers’ rates. Con Ed wanted the rate hike in order to, among other things, spend over $350 million to build new transmission pipelines, replace smaller pipes with larger ones, and extend the life of a liquefied natural gas plant. Environmental advocates from the Pace Energy and Climate Center and the Sane Energy Project argued to regulators that the company did not sufficiently justify why these projects were necessary, identify alternatives, or evaluate whether the investments were consistent with the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), New York’s landmark climate law.

In defending its investments, Con Edison argued that these projects were needed to meet gas demand, and that because the state had not amended or eliminated “the Company’s obligation to serve,” they were “just and reasonable.”

The New York Public Service Commission (PSC), which regulates utilities and must approve their requests to raise rates, agreed. In its decision, it wrote that despite the passage of the CLCPA, “the Company’s obligation to provide service has not changed.”

“Existing law has evolved over a century of fossil fuel use and the development of existing infrastructure,” said Justin Gundlach, an attorney at the Institute for Policy Integrity, a nonpartisan think tank. “There is a lot of work to be done identifying where the CLCPA and existing law need to either be amended or reinterpreted.”

The “obligation to serve” isn’t the only part of the law in New York that’s feeding into gas expansion. There’s also the “100-foot rule,” which requires utilities to hook up new customers who live within 100 feet of a gas main for free, a subtle incentive for new building owners to choose gas. The cost incurred by the utility is subsidized by its existing customers. “This subsidy distorts the market and creates an unlevel playing field that discourages consumers from properly considering other heating and cooling alternatives,” wrote NY-Geo, a trade association that represents the geothermal heat pump industry, an electric competitor to gas heating, in a recent filing to the PSC.

California has a similar regulation that allows developers to get a discount on the cost of hooking up to the gas system based on how many new gas appliances they plan to install. “Why is that still happening?” asked Matt Vespa, a senior attorney at Earthjustice. “Those [costs] should wholly be borne by the developer. That’s a current rule that we think needs to be revised immediately.” According to Vespa, the California Public Utilities Commission has the power to change the regulation without new legislation.

California also has a law on the books called the Natural Gas Act, which requires the state’s energy planning agency to issue a report every four years that identifies “strategies to maximize the benefits” of natural gas. That rule is the basis for a lawsuit recently filed by Southern California Gas Co., the state’s largest gas utility, accusing the agency of minimizing gas in its most recent write-up.

Michael Colvin, the director of California energy policy at the Environmental Defense Fund, told Grist that the Natural Gas Act is just a procedural rule that requires the state to issue a report, and he didn’t think the suit held water. But he said there will need to be additional legislative action to reconcile California’s decarbonization goals and its buildings, and cleaning up that bit of legislation might be part of it.

“Obligation to serve” laws aren’t the same in every state, and Turner said that it’s worth looking at the way they are written when thinking about whether or not they’ll need to be amended. California’s provision orders utilities to provide “efficient, just, and reasonable service.” “You could argue that this is just saying that public utilities have to make sure that people have adequate energy service, but doesn’t necessarily say that you have to keep giving them gas,” Turner said.

And because California gives more authority to local governments than, say, Massachusetts does, the other preemptions that came up for Brookline’s bylaw, like the ability to create local building codes, have not been raised in the California cities that have passed restrictions on gas in new buildings. But according to Colvin, the state will still need new laws or regulations to address the myriad challenges of transitioning away from gas, like avoiding stranded assets and ensuring rates remain affordable.

Earlier this year, regulators in California and New York opened up new “gas planning” proceedings to study these questions, and the attorney general’s office in Massachusetts is urging its regulators to do the same. These proceedings offer a potential space to tackle some of the tensions between existing laws and climate laws.

Gundlach said that in New York, the issues around “obligation to serve” could be addressed by changing public service law, but they also might be fixed through regulatory changes, or on an ad-hoc basis in rate cases. “Those three are not mutually exclusive,” he said.

Environmental groups and other organizations are already pushing for regulatory reforms. In New York, the Natural Resources Defense Council submitted testimony to PSC asking whether the obligation to serve could be generalized to require utilities to provide heating and hot water, rather than gas. More than 50 organizations and businesses signed a letter demanding that the PSC find out how much the 100-foot rule costs customers. Pace submitted a new framework that the commission could adopt to strategically reduce the demand for gas, including changing the gas service application so that developers have to “adopt alternatives to gas wherever feasible.”

In Massachusetts, state legislators are testing out a different fix that would allow Brookline to reinstate its gas restriction. State representatives Tommy Vitolo and Kay Khan are working on a bill that would require the Board of Building Regulations and Standards, the agency that oversees the state building code, to create a new “Clean Heating Code” that towns could adopt. This optional code would require that all new construction and major renovations utilize electricity or fossil fuel–free technology for heating and hot water. As a state-level code, it would be on equal footing with public service law and could potentially override “duty to serve” arguments. Vitolo said the state created a similar optional building code a decade ago with stricter energy efficiency requirements, and communities representing more than 75 percent of the population have since adopted it.

Vitolo lives in Brookline and helped put together the town’s bill to limit gas in new buildings. He said the bill wasn’t going to eliminate the problem of building emissions, but it was a first step. “When you’re in a hole, the first thing to do is stop digging,” he said. “The most expensive time to change your heating system is after it’s already been installed. The cheapest time to change your heating system is before you even start designing it.”