There was a brief, heady time in the late ’00s when it seemed like energy efficiency was finally going to get the spotlight. For years — decades, really — efficiency geeks lamented that the only job-creating, money-saving, productivity-enhancing energy option available was perpetually marginalized while far more expensive options (cough*nuclear*cough) were subject to endless public discussion. Since 1970, the U.S. economy has tripled in size; in that time, 3/4 of the demand for new energy services has been met by efficiency, not new energy supply. Three-quarters! A bigger contribution than any single energy source. And yet … crickets.

But then efficiency started catching on! People started writing about it in major publications. A few glimmers of bipartisan consensus in Congress appeared. Hope abounded.

And then the financial crisis and the Tea Party arrived and everyone went back to ignoring it. Blarg.

Nonetheless! Efficiency remains the largest untapped pool of short-term, cost-effective reductions in pollution and greenhouse gases.

Along those lines, I highly recommend the new report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. It goes after the Big Kahuna, i.e., it tries to get a sense of the total potential for efficiency in the U.S. economy.

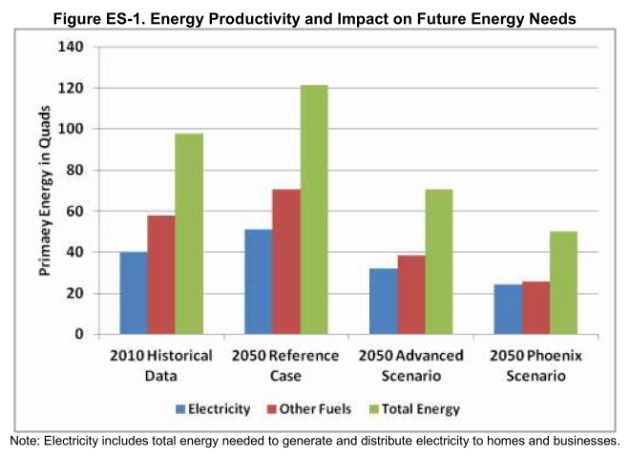

Obviously, when taking on such a broad and abstract subject, there are lots of assumptions and some complicated economic models involved. If you’re into the gory details, see the appendices. The basic idea is, they take the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook as a reference scenario for what energy demand will look like in 2050. Then they model the effects of two different alternative paths: an “advanced” scenario, in which existing advanced efficiency technologies achieve broad penetration, and a “phoenix” scenario, with the same penetration plus big shifts in infrastructure and the built environment. Phoenix is the “go big” scenario for efficiency. Here’s the result:

Energy efficiency can reduce energy demand. (Source: ACEEE)

The advanced scenario reduces projected energy demand by 42 percent, the phoenix scenario by 59 percent. Needless to say, that would avoid a hell of a lot of greenhouse gas emissions.

Neither scenario would be easy. Both would require enormous shifts in investment and, most likely, big changes in law and regulation. But it is a huge mistake to see efficiency spending as a “cost” in the way that the Iraq War or Superfund cleanups are a “cost.” These are investments, and they pay rich returns. Here’s how:

First, households and businesses will see lower energy bills as the level of energy efficiency improves over time. As they maintain (or even increase) their own economic activity through these productivity improvements, the growing energy bill savings will act much like an extra form of income that provides an important stimulus for the other sectors of the U.S. economy.

It’s worth pausing here to emphasize this: efficiency improvements act as a kind of ongoing economic stimulus, freeing up resources for more productive uses. In a crappy economy, you’d think this would be of interest!

Second, and related to this first improvement, the efficiency gains will allow households and businesses to redirect the flow of spending away from the more costly energy sectors. The net result is that households and businesses will have more money available for the purchase of other goods and services. As it turns out, those other sectors of the economy tend to be more labor intensive. Hence, the increased spending, in turn, provides a larger net employment benefit for the nation’s economy …

Worth pausing again here to draw this out. Fossil fuel energy — the stuff we buy to heat our houses and run our cars — has low labor intensity. That is to say, investments in it create few jobs relative to investments in other economic sectors (including, but not only, clean energy). Anything that shifts investment from fossil fuels to other economic sectors will, therefore, all things being equal, create more jobs, not just in efficiency itself, but across the economy. Put more succinctly: saving energy creates jobs. This is a poorly understood aspect of efficiency that has huge implications.

Back to the grand conclusion:

[W]e estimate that the combined effect of the efficiency investments over time, together with growing energy bill savings, will drive a steady increase in the demand for labor so that by the year 2050 the economy will provide a net increase of 1.3 to 1.9 million jobs. Net gains to the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2050 are estimated to be on the order of 100 to 200 billion dollars per year. Both the employment and GDP benefits are on the order of tenths of a percent above the 2050 Reference Case.

So, just by shifting our “recipe of investments” — not spending more, just spending differently — we could create more jobs and increase economic productivity while cutting our projected energy use by almost 60 percent.

This completely explodes the “environment vs. economy” canard. It’s good for the atmosphere, good for the economy, good for public health, good for employment, good for the baby Jesus … and yet, not only do we not do it, we hardly ever even talk about it! Sigh.

——

Addendum: You’ve probably heard a lot of people recently poo-pooing efficiency through reference to the “rebound effect.” The idea is, if efficiency makes energy services cheaper, people don’t pocket the savings — they just use more of the services. So energy use doesn’t actually fall much.

Author David Owen has made hay about this in The New Yorker and in a new book. And of course, whenever there’s an opportunity to crush the dreams of hippies (and get lots of media attention), the Breakthrough Institute is first in line. Here’s their report [PDF] on it.

The rebound effect has enormous public appeal, because there’s nothing the public loves so much as a counterintuitive, “hippie solution not actually a solution!” piece. Every so often, you see a new wave of stories on it, as has happened in the last year or two.

But energy economists don’t take it that seriously. The folks at CO2 Scorecard did a full report in response to Breakthrough’s. It found:

In this research note we refute this policy message and show that the BTI, as well as its champions in the media, have overplayed their hand, supporting their case with anecdotes and analysis that don’t measure up against theory and data. Our fact-checking revealed that empirical estimates of energy rebound cited by the BTI are over-estimated or wrong, and they contradict the technological reality of energy efficiency gains observed in many industrial sectors.

Pause, as this is important. This is not speculative stuff: efficiency gains have actually happened in various sectors and the rebound effect has been marginal. You don’t need models and assumptions to find this out, you just have to look at the record. Continuing:

We provide new statistical evidence to show that energy efficiency policies and programs can reliably cut energy use — a finding that is consistent with the policy stance of leading experts and organizations like the US Energy Information Agency (EIA) and the World Bank. Additionally, we take our policy message one step further — by using new insights from the emerging multi-disciplinary literature on “energy efficiency gap”, we recommend that the world needs more energy efficiency policies and programs to cut greenhouse gases — not less as implied by the BTI and its cohorts in the media.

Breakthrough responded, as is their wont, by claiming that their intentions were misunderstood. They did not mean to diss energy efficiency! That was just the clear implication and the conclusion of every fair observer and the whole reason their report got media attention. All a big misunderstanding!

Anyway, if you’re interested in following the subsequent back-and-forth, read this follow-up from CO2 Scorecard. Long story short: The BTI report was crap, the rebound effect is wildly over-hyped, and efficiency is great. We should start talking about it more. And, y’know, doing it.

——

UPDATE: The crack above about the BTI report being “crap” — and, indeed, the entire addendum — is just douchey. I retract and apologize here. The rebound effect is a complicated thing and the subject of a great deal of academic literature; I shall endeavor to approach the subject with more humility.