The Island Energy Dashboard gives residents a real-time look at how much electricity they’re sucking from the grid. When Puget Sound Energy announced plans to build a new substation to meet rising electricity demand on Bainbridge Island, Wash., in 2009, it apparently didn’t know who it was dealing with. Bainbridge is a well-to-do suburb of Seattle (a 35-minute ferry ride will drop you right in downtown), and home to more than a few techies, computer programmers, and folks who have letterhead with lots of fancy degrees in front of their names.

The Island Energy Dashboard gives residents a real-time look at how much electricity they’re sucking from the grid. When Puget Sound Energy announced plans to build a new substation to meet rising electricity demand on Bainbridge Island, Wash., in 2009, it apparently didn’t know who it was dealing with. Bainbridge is a well-to-do suburb of Seattle (a 35-minute ferry ride will drop you right in downtown), and home to more than a few techies, computer programmers, and folks who have letterhead with lots of fancy degrees in front of their names.

Eric Rehm, a software-engineer-turned-marine-biologist, says that “a mosh pit of community organizations” came out to community meetings to discuss the electric company’s proposal. “There were enough geeks there that we said, ‘Can we see the [electric grid] load data? Can we have that data in real time?'”

Rather than cutting down a bunch of trees to enable the island to use more electricity, they wondered, “Can we just use less?”

The question spurred a unique experiment in community energy conservation that may hold lessons for the rest of us as we try to cut back our electricity use to save money and the climate.

Under the banner of Repower Bainbridge, a coalition of local residents, organizations, and government officials has set out to cut the island’s electricity use by 15 percent in three years. With $4.9 million in stimulus money via the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Buildings Neighborhood program, Repower Bainbridge has conducted more than 1,500 free “home energy check-ups” — a quicker version of a home energy audit that shows you how to trim down your energy use. The initiative ultimately aims to do 4,000 of these checkups, with the goal of inspiring 2,000 home upgrades — that’s almost a quarter of the homes on the island — and creating a few green jobs in the process.

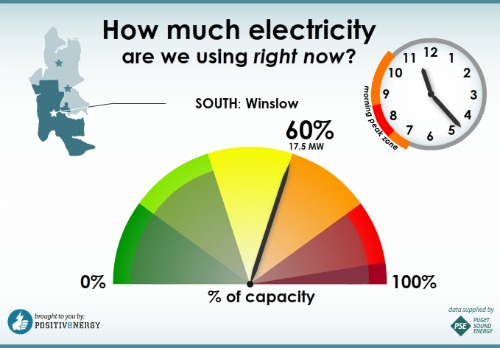

To help the community get its head around the challenge, Positive Energy, a local nonprofit organization, working closely with Puget Sound Energy, has created a first-of-its-kind, web-based community energy “dashboard.” This color-coded oh-shit meter provides an up-to-the-minute look at how much juice the island is sucking from the electric grid. When the needle dips into the red, the message is clear: Cut down your energy use or the power company will be here cutting down trees for that new substation.

For those who don’t obsess over the energy dashboard day in and day out, Positive Energy has installed dashboards all over the island. Bainbridge Bakers, Bay Hay and Feed, the Treehouse Café, Eagle Harbor Books — they all have dashboards on digital display. So do some of the ferries that shuttle island residents back and forth from the mainland.

To augment the dashboards, Repower Bainbridge sends out suggestions and promotions via Twitter and Facebook aimed at getting people to conserve energy — and when that’s not possible, to shift energy use to “off-peak” hours. On the island, like anywhere, the real crux of the problem is just a couple of hours a day when the electric grid is pushed close to its limits — typically midmorning and early evening, but with big spikes on hot summer days when we fire up the A/C.

By convincing people to wait to do their laundry and dishes until late in the evening, turn down the heat on their hot water heater, or throw on a sweater and dial down the thermostat, Repower Bainbridge essentially creates more capacity for the grid, building a little more wiggle room into the existing system.

Another technique the islanders have tried is sparking a little friendly competition. Inspired by the Tidy Street Project in England (and using the same open-source software), Repower Bainbridge launched an energy conservation competition last summer called “Electric Avenue.” The group stenciled giant graphs onto two streets on the island, charting neighborhood energy use over the course of three months. The idea was to raise awareness of energy use and convince locals to join the good fight.

While the project did not significantly decrease energy use, Rehm says islanders learned some valuable lessons. First among them is that what worked in a dense urban area in England was not necessarily a recipe success in a more suburban or rural area. The street that trimmed its electricity use more in the Electric Avenue challenge was a little more tightly laid out, making the street graph more visible to the frequent passersby on the sidewalks. The other street was more spread out and hilly, making the graph less prominent and probably leading to less interaction among neighbors. “Some neighborhoods are more neighborly than others,” Rehm says.

But here again, the islanders may have devised a tech-tastic end-run around the problem. The groups involved in Repower Bainbridge are now talking about firing up the Electric Avenue project using “virtual neighborhoods” — church groups, for example, or local members of the Sierra Club. Rather than painting the results on the streets, organizers could display them on the Web. It’d be like a community softball league for energy geeks.

I know, only on Bainbridge, right? But islands tend to be harbingers of what’s coming for the rest of us. Maybe it’s time to fire up a little neighborly competition in your community. It’s tough to save the world by yourself.