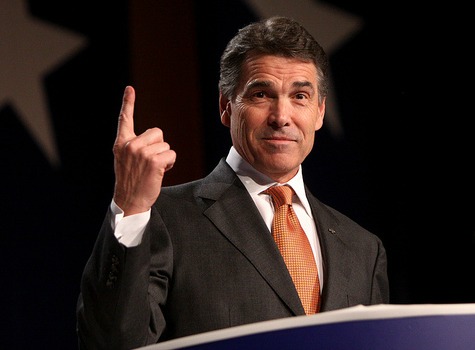

1.2 million jobs? Try again, buddy.Photo: Gage SkidmoreCross-posted from Council on Foreign Relations.

1.2 million jobs? Try again, buddy.Photo: Gage SkidmoreCross-posted from Council on Foreign Relations.

The centerpiece of Rick Perry’s economic plan, released this morning, is a pledge to create 1.2 million energy jobs. Mitt Romney has already promised to create nearly 1.5 million energy jobs. Why do we keep hearing numbers in this ballpark? And are they plausible?

A quick preview since this is a long post: I see about 620,000 jobs max, of which about 180,000 are actually in the energy sector. The real world numbers are almost certainly quite a bit lower.

Now back to the analysis.

The figures appear to come largely from a study prepared by the consultants Wood Mackenzie and published last month by the American Petroleum Institute (API). (Perry explicitly footnotes it in his plan.) That study found that “U.S. policies which encourage the development of new and existing resourses could, by 2030… support an additional 1.4 million jobs”. About 1.2 million of those are based on expansion of U.S. production by 6.0 million barrels per day of oil and 22.4 billion cubic feet of gas per day by 2030, along with approval of the Keystone XL pipeline. (The rest come from future U.S.-Canada pipelines). The study projects interim impacts of 700,000 new jobs by 2015 and 1.1 million by 2020.

WoodMac assumes five policy changes in order to generate this expansion, all of which are echoed in Perry’s and Romney’s plans:

- Open the Eastern Gulf of Mexico, parts of the Rocky Mountains, the Atlantic and Pacific Outer Continental Shelves, the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge, the Alaska National Petroleum Reserve, and Alaska offshore to drilling. There is certainly a sharp contrast here with the Obama administration. Whether a new president could make all of these things happen is another question – in many cases, the nearby states would be strongly opposed.

- Gulf of Mexico permitting is returned to its previous pace. It isn’t clear, though, that this is actually a new policy – given the resources by Congress and a bit of time, the Obama administration might well do the same.

- Lifting of the drilling moratorium in New York State. Neither Perry nor Romney, of course, has any power over this, so it’s inappropriate to include it in estimates of federal policy.

- Forgo federal regulation of shale gas and tight oil development, including, in particular, tighter regulation of fracturing and water disposal. The assumption here is that federal rules would be stricter than state ones; WoodMac assumes that they would add 30 cents per thousand cubic feet to the cost of producing gas. It’s not clear that that’s true – states like clean water too.

- Approve the Keystone XL pipeline and other future U.S.-Canada pipelines. This may or may not be a policy shift from the Obama administration – we’ll have to wait and see what happens with Keystone XL first.

There are, in essence, two problems here: the estimates assume that the Obama administration will be harsh toward oil and gas, and that a new president could roll over the states and Congress to be much more permissive. To the extent that those beliefs aren’t true, the jobs estimates will be too high.

[UPDATE: I’ve tweaked the next two paragraphs to reflect a more careful state-by-state and policy-by-policy analysis of the numbers in WoodMac’s appendix than I had in the initial post, and adjusted the bottom line numbers accordingly. The basic contours remain the same.]

Let’s put some numbers on this. Many of the projected jobs come from opening up new areas to production. As I noted above, though, many of the barriers to doing that may be at the state level and in Congress. How much might accounting for that blunt the jobs projections? Let’s assume that California blocks development, and that half of the Atlantic development (ex-Florida) is held up by states. I’m not sure how to handle Florida itself, which has a ban on drilling in state waters (there’s also a statutory bar on Eastern Gulf of Mexico development); let’s say, I think very generously, that half of the projected drilling materializes. Let’s also say that the assumptions about future Obama administration slowdowns on Gulf of Mexico permitting are probably overstated, but still assume that a new president would speed things up somewhat, as a result increasing production from Texas and Louisiana by half as much as WoodMac estimates. All in, we’ve cut the jobs projections by about 330,000. (Alternatively, if you want, you can think of this as loosely as letting production go ahead in much of California but having Florida drilling — the statutory bars to Eastern Gulf of Mexico development that make opening that up really hard – remaining out of bounds.)

Now lets look at the onshore numbers. About 40,000 jobs come from New York State, but as I noted earlier, that’s not a matter of federal policy, so scratch them all. WoodMac reports that onshore regulatory barriers cost another 300,000 jobs. I observed above, though, that the study probably exaggerates the likely stringency of Obama administration regulation relative to state policy, so it’s fair to slice this in half (actually, it’s generous not to set them closer to zero). So far, then, we’ve cut 520,000 of the projected jobs.

The final 270,000 projected jobs, or about 20 percent, come from new U.S.-Canada pipelines. This number is grossly overstated. According to WoodMac, “these jobs are primarily a result of U.S. services and the production of capital and intermediate goods exported to Canada for the development of the oil sands”. But blocking U.S.-Canada pipelines isn’t going to stop Canadian production from growing: it would slow things down, but ultimately, other export routes would likely materialize so long as oil prices were high enough. Those U.S. jobs wouldn’t disappear. To be generous, though, let’s say that delays and uncertainty associated with building other pipelines would kill 20 percent of the U.S. jobs, and that there’s a 25 percent chance that the Obama administration will kill all pipelines; credit 14,000 jobs to a new pro-pipeline policy, 256,000 fewer than WoodMac projects.

Let’s take stock. We started with 1.4 million new jobs; we’ve identified about 780,000 of those that either will exist regardless of what a new president does, or whose fate depends strongly on states’ decisions. That leaves us with a more realistic estimate of about 620,000 jobs.

But we’re not done yet. WoodMac estimates that for every direct job that the oil and gas industry generates, 2.5 jobs are created elsewhere, either in suppliers or in the broader economy as oil and gas workers spend the money they make. That 620,000 job estimate, then, corresponds to 180,000 jobs in the oil and gas industry itself. Some of those would come at the expense of jobs elsewhere in the economy — indeed, in the longer term, many of them would. The same thing goes for the induced and indirect ones.

The other caveat to the WoodMac estimates is that they assume high and steadily rising oil and gas prices. Oil prices start at $80 per barrel in 2012 and rise to $160 (in constant dollars) by 2030. WoodMac assumes that adding 6 million barrels per day of extra U.S. production won

‘t blunt that increase, but I don’t buy that – we’re talking about a lot of oil. In reality, if production were to start increasing the way WoodMac claims it can, the price impact would likely deter some of the other development it projects. Of course, lower prices would also help the rest of the economy, but that isn’t part of the WoodMac projections or of Romney’s and Perry’s jobs claims.

Natural gas prices, meanwhile, start at $6 per thousand cubic feet in 2012 in the WoodMac model (for what it’s worth, spot prices are barely half that today), and rise to $12 by 2030; once again, policy changes don’t affect that. That’s a pretty high price projection, particularly for a scenario where you’re expecting a huge boost in natural gas supplies. Alas, as with the oil case, lower prices mean that many of the projected energy sector jobs won’t materialized.

Which brings us to the bottom line. The numbers that Perry and Romney are offering for job creation in the energy sector are unrealistic. They assume that they will be reversing deeply anti-industry Obama policies that don’t actually exist (which is not to say that the Obama policies have no flaws), ignore real constraints at the state level, and don’t properly account for market dynamics. Six hundred thousand is a pretty hard upper limit for the number of jobs that a new policy might create by 2030, of which fewer than two hundred thousand might actually be in oil and gas. Taking into account market dynamics would lower those numbers further, quite likely much further; more generous assumptions about Obama administration energy policy would too. That’s still nothing to sneeze at – but it’s not 1.2 million jobs either.