In December 2018, the World Bank made a public commitment: The international financial institution, known for providing funding and policy advice to developing countries, would align its spending more closely with the goals of the 2015 Paris Climate Accord.

But that promise didn’t exactly pan out. According to a new report, the World Bank Group has since financed nearly $15 billion across 144 fossil fuel projects and policies, many in areas of the world already experiencing some of the most dire consequences of climate change.

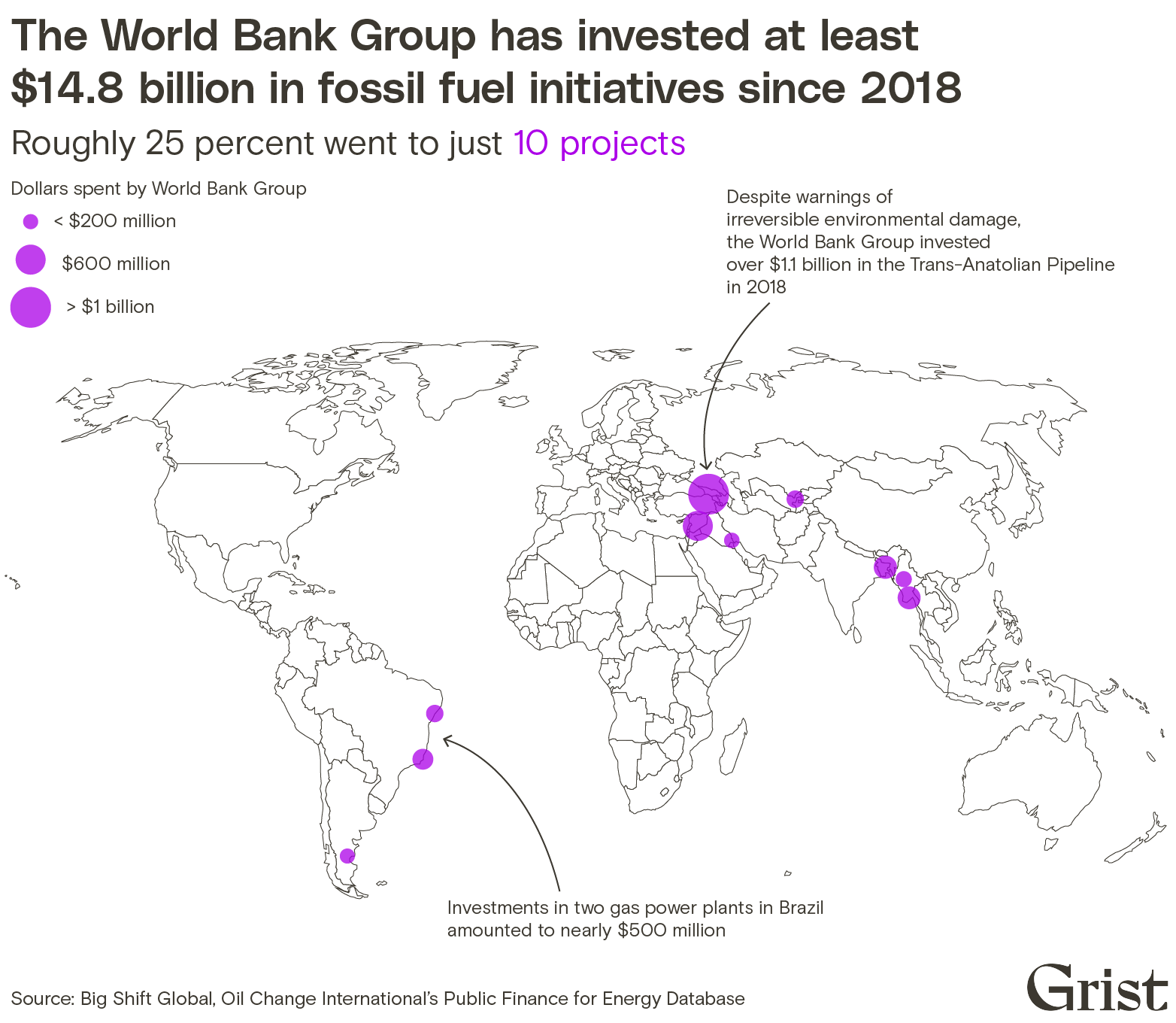

The report comes from Big Shift Global, a coalition of NGOs that work to bring transparency to global energy investments, which analyzed public data from Oil Change International’s Public Finance for Energy database. It found that net new investments from the World Bank Group between the fiscal years of 2018 to 2021 amounted to roughly $14.8 billion.

“There is no excuse for a new fossil fuel project to be constructed,” said Elaine Zuckerman, who left the World Bank in the 1990s to hold the group accountable for the gender and climate impacts of its decisions. Her organization, Gender Action, is a member of Big Shift Global and a contributor to the report.

About a quarter of the $14.8 billion identified in the report is associated with just ten World Bank-financed projects, the most expensive of which is the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline. The natural gas pipeline, which will stretch roughly 1,150 miles across the entire country of Turkey, is expected to deliver 16 billion cubic meters of gas from Azerbaijan to Europe annually — more than triple Azerbaijan’s current annual exports.

Before making the $1.1 billion investment, the agency conducted an environmental and social impact survey, which warned that the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline could have “unprecedented” and “irreversible” social and environmental consequences on water quality, air quality, and worker health and safety. The investment was still green-lit.

The report is not the first time the World Bank has faced environmental criticism. While the mission of the World Bank Group is to end extreme poverty, the institution has faced multiple controversies for allegedly ignoring the rights of Indigenous peoples and rigging data to boost China’s climate ranking. Just last week, current World Bank President David Malpass, came under fire for balking at a question about whether human-related greenhouse gas emissions are causing climate change. “I don’t even know — I’m not a scientist,” the Trump appointee said to a New York Times reporter. Malpass has since apologized.

While multiple projects highlighted by the report list job creation as a major benefit, Zuckerman says local communities often see less of the financial benefit and much more of the social and environmental consequences once construction for fossil fuel projects begins.

“My view, based on more than 40 years of experience with the World Bank is that the biggest beneficiary of world bank loans are these very large corporations — often multinational corporations,” she said.

From a strategy standpoint, clean energy projects are better, cheaper vehicles for job creation than fossil fuel projects, said Jim Barrett, a energy and environmental economist who consulted with the World Bank in 2021.

It’s not a matter of whether or not a fossil fuel investment creates jobs, he said. “It will no doubt create jobs. The question is, is there a better, more productive way to invest a million dollars in developing countries? And the answer is yes.”

A spokesperson from the World Bank Group told Grist: “We dispute the findings of the report: it makes inaccurate assumptions about the World Bank Group’s lending. In fiscal year 2022, the Bank Group delivered a record $31.7 billion for climate-related investments, to help communities around the world respond to the climate crisis, and build a safer and cleaner future.”

But the report’s authors argue those investments can end up locking communities and economies into a future dependent on fossil fuels “at a time when politically, scientifically and in the real world, the case to divest from fossil fuels and invest in clean renewables should have been obvious.” Leaders from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are expected to meet in Washington, D.C., this week to discuss a range of investment questions moving forward.