This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

The Samascott Family has been growing apples on their self-named orchard in Kinderhook, New York, since the 1940s. Like many farms in Upstate New York, Samascott Orchards has had to make big adjustments over the decades to try to remain profitable. One of those changes was shifting from planting larger apple trees to smaller ones, which can yield more apples per acre of farmland. While this strategy makes good economic sense most years, it can create challenges for growers during dry summers like this one.

“We used to have much bigger apple trees; they could sometimes go months without much rain at all,” said owner Gary Samascott. “Now with these new smaller trees with much more root systems and much higher yield per acre, you can go maybe three weeks without water.”

At first glance, Upstate New York might not look like it has a problem with precipitation. After all, when Americans think of the term “drought,” chances are they think of the Western U.S. — dead lawns, disappearing reservoirs, and shrinking snowpack. But low rainfall is also an issue for other parts of the country, including the Northeast, that many people don’t necessarily associate with dryness.

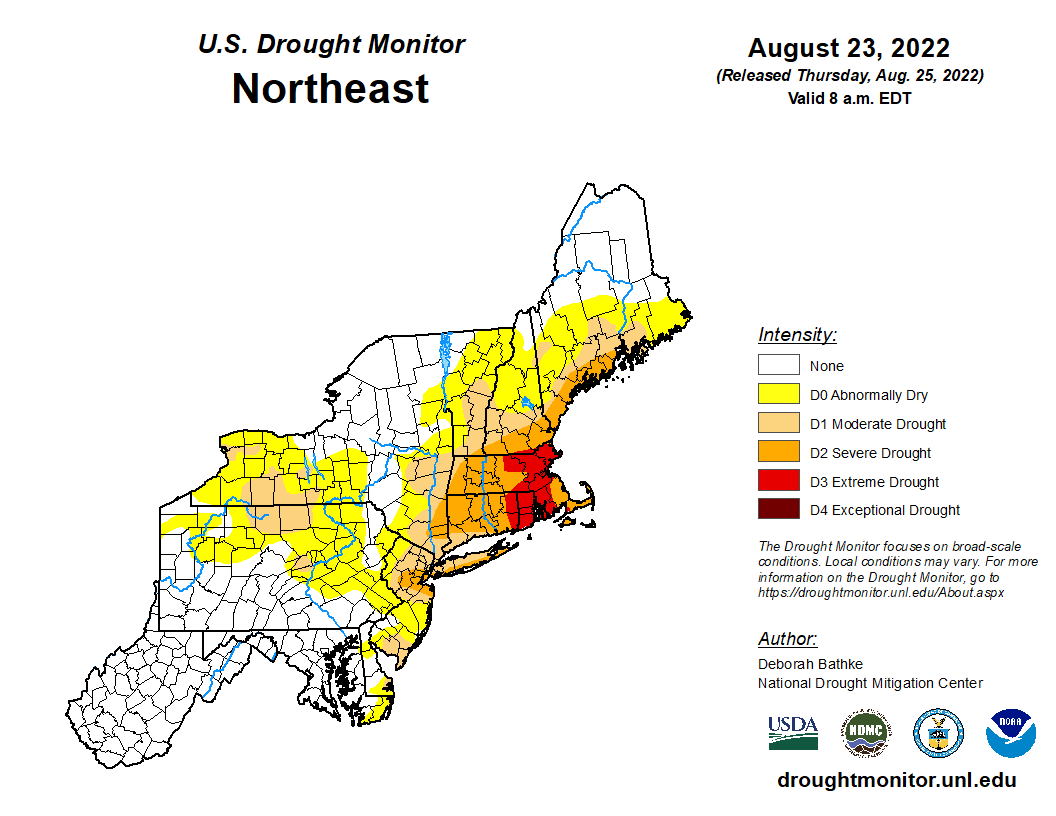

This summer, rainfall has been relatively absent from many parts of the Northeast. New England has been particularly affected: For the first time in seven years, all of Massachusetts is currently experiencing some level of drought – a “flash” development based on conditions over the last few weeks. All of New York City is also experiencing drought conditions, with some areas considered to be in severe drought, as rainfall totals remain well below typical levels for the summer months.

“Different parts of the country have different ‘normal’ amounts of rainfall,” said Nick Bassill, Director of Research and Development at the Center for Excellence in Weather and Climate Analytics at State University of New York at Albany. “If you’re down like 10 inches on the year in Las Vegas that is almost all the rainfall that you would get, versus here in Albany normally we get 50 inches of rain.”

The sheer difference in normal rainfall from region to region exposes one of the key differences between dryness and drought. What shifts an area from a period of pronounced dryness into a period of drought is not dependent solely on one metric, like rainfall. Besides the lack of precipitation, drought is determined based on relative severity, duration, and even the accompanying temperature. These factors are viewed together to create tools like the U.S. Drought Monitor, which can alert both average citizens and emergency managers as to when an area is considered dry versus experiencing full-blown drought.

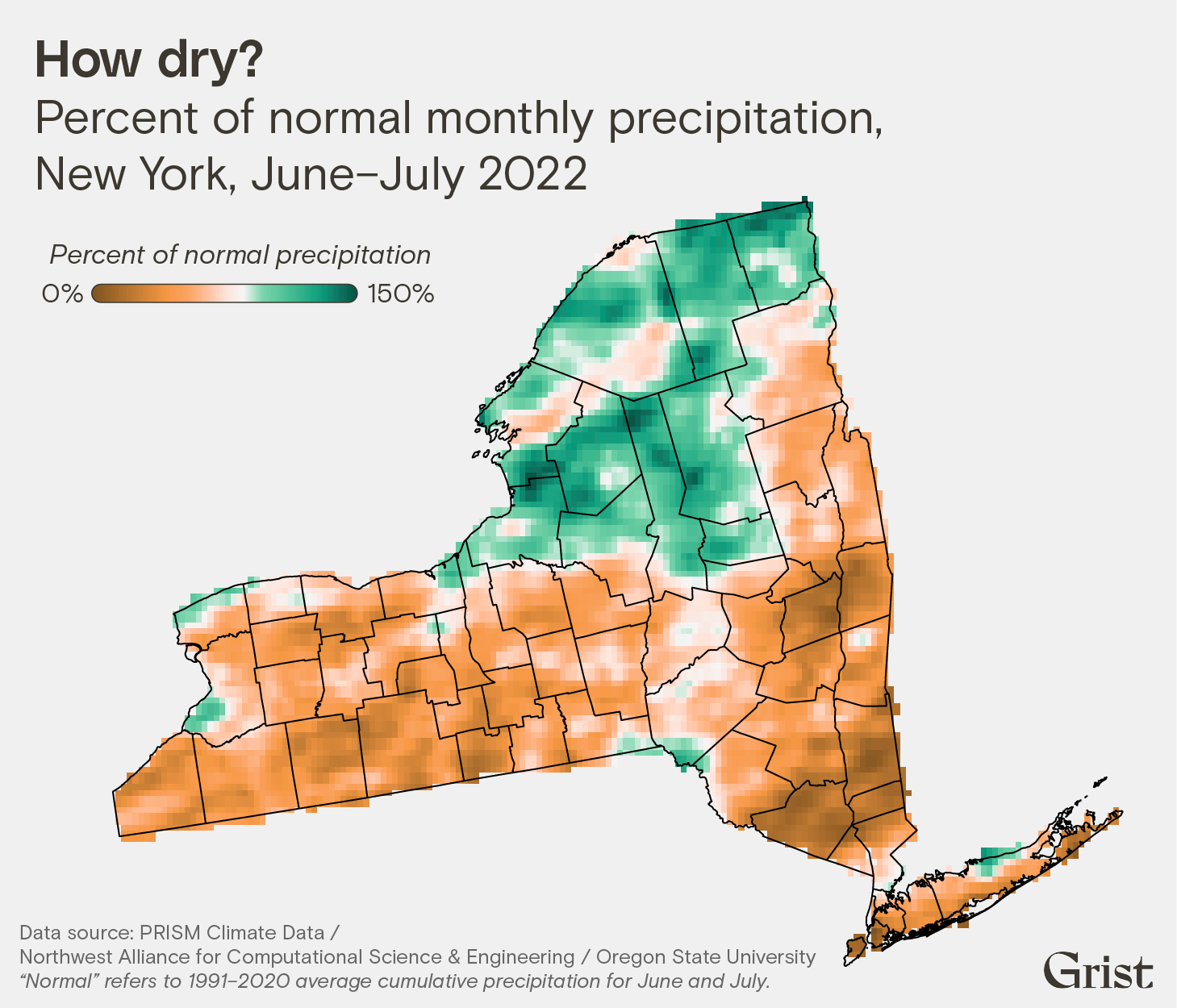

One thing to remember, Bassill said, is that dryness can exist on a hyperlocal scale. “In the summertime, most of our rain comes from pop up thunderstorm type rain events, where it rains really hard for like 20 minutes or whatever, and then it’s done,” he said. Some of these events are so small they may affect one borough and not the next. “That can make the difference between being on the dry or drought side versus ‘oh, actually, we’re fine where we are.’”

Products like the U.S. Drought Monitor can help cities forecast the effects of either dryness or drought on agriculture and water resources. Weeks of dryness can have long-lasting impacts on crops, even after a heavy summer rain. The ground can become so parched that it soaks up all the rain right away, making it harder for plants to absorb enough water. A heavy coating of snow, however, can melt progressively, releasing water at just the right rate to moisten the soil and hydrate plants.

Even outside of official drought zones, growers are among the first to feel the consequences of abnormal precipitation. Limited or delayed rainfall can shift when blooming seasons take place for certain fruit trees. This can present serious problems for farmers like Samascott who are trying to manage their growing and harvesting seasons. Additionally, if growing seasons for common fruits like strawberries or apples (usually late May or early June) are dry, farmers may need to spend money on irrigation technologies, like drip irrigation, to make sure that water reaches the roots of these plants.

Back on Samascott Orchards, Gary Samascott says his family’s apple trees benefit from having drip irrigation built into the watering network to protect from periods of low rainfall. He noted that without drip irrigation – something not found on every farm – extended periods of little rain “could outright kill the trees.”

Beyond fruit bearing trees, a relatively short-term lack of water can threaten ornamental trees in suburban and urban environments. Bassill explains that trees that survive periods of dryness can become physically weaker, causing downstream infrastructure problems. The trees are “a little bit more susceptible to being blown over, and having tree limbs blown off,” he said. “That kind of stuff causes lots of power outages.”

Bassill recalls the remnants of Hurricane Isaias, which in 2020 knocked down thousands of trees throughout New York. The weeks preceding the storm’s remnants reaching New York experienced significant dryness – as little as 20 percent of average rainfall in parts of the state. Researchers believe that drought conditions preceding the storm weakened tree root systems throughout the New York City tri-state area, exacerbating storm damage.

Though much of the country is currently experiencing parched conditions, it’s unlikely the Northeast will ever see the same kind of long-term drought ravaging the West. Most climate change studies agree that the Northeast will likely get rainier in general. But if the region experiences dryness this severe in the future, the big rain that’s likely to follow may bring more challenges than relief.