This story is part of Grist’s Summer Dreams arts and culture series, a weeklong exploration of how popular fiction can influence our environmental reality.

The first chapter of Twilight begins with 17-year-old Bella Swan getting dropped off at the Phoenix airport, preparing to trade the hot Arizona sun for the soggy gloom of Forks, Washington. “In the Olympic Peninsula of northwest Washington State, a small town named Forks exists under a near-constant cover of clouds,” Bella narrates in a tone that’s equal parts Wikipedia entry and teenage snark. “It rains on this inconsequential town more than any other place in the United States of America.”

Even though Bella is not initially a fan of Forks (out of context, you’d be forgiven for thinking you were reading an anti-travel brochure), the old logging town’s moody, verdant aesthetic has become a central part of Twilight fandom. It didn’t take long after Twilight came out in 2005 for fans to start flocking to Forks, where the fictional flames of Bella and Edward Cullen’s romance began. Forks was, in Bella’s words, “beautiful, of course; I couldn’t deny that. Everything was green: the trees, their trunks covered with moss, their branches hanging with a canopy of it, the ground covered with ferns. Even the air filtered down greenly through the leaves. It was too green — an alien planet.”

Twilight lovers’ attachment to Forks’ natural setting proved stronger than previous visitors. “The thing about Forks is — and it happened with me, it’s happened with thousands of people — people come to Forks, and then they feel like Forks is the hometown they never had,” said Lissy Andros, a Twilight fan who moved from Texas to Forks in 2009 and now directs the town’s Chamber of Commerce. “They feel a real connection in their heart to this little town in the Pacific Northwest.”

But at that time, the town that Twilight fans found themselves falling in love with didn’t actually exist — at least, not in the way Stephenie Meyer, the author of the series, described it. Sure, Forks was a real place, population 3,900, with towering spruce and an abundance of rain, but it was mostly seen as a stop along the way to other places: the mossy Olympic National Park or Washington’s coastal beaches, with their craggy rocks shrouded in the ocean mist. The town historian, Christi Baron, remembers a travel writer penning a mean review of Forks just before the first Twilight book came out, describing the town as something like “a festering boil” on the Peninsula.

As for the area’s natural beauty, it didn’t always inspire unity among the locals. While the Twilight books imagined Forks as an idyllic setting for a century-old vampire-werewolf rivalry, the real tension in the town prior to 2005 was between loggers and environmentalists. But Meyer’s mythological version of Forks turned it into a destination in and of itself, attracting tens of thousands of tourists to the town every year. Now, more than a decade after the peak of Twilight mania (and with all five movies hitting Netflix this summer), fans are continuing to transform the town into something more closely resembling the romantic wilderness of their vampire-filled dreams.

Today, it’s hard to imagine Twilight being set in any place other than Forks, but Meyer’s choice of setting could have easily gone a different direction. The decision, it turns out, was inspired, sight-unseen, by a bit of quick Googling. “I knew I needed someplace ridiculously rainy,” Meyer wrote in a blog post about Twilight’s backstory. (She knew that her vampires would sparkle in the sunlight, so anywhere with clear skies threatened to expose their secret to the masses.) Meyer landed on Forks, which averages 120 inches of rain per year, making it one of the wettest places in the Lower 48. In theory, she could have chosen Humptulips, Washington, or maybe Port Orford, Oregon.

Shortly before finalizing the manuscript, in the summer of 2004, Meyer made her first trip out to the Olympic Peninsula. Her trek to Forks — one that would later be repeated by countless teens — yielded a town that was “eerily similar” to how she had pictured it. There were a couple of exceptions, like the town’s timber industry. Driving into Forks, you’re bound to come across clear-cuts, those razed landscapes where felled, narrow trees are strewn across a reddish-brown slope of stumps.

“The logging presence was much more evident than I’d pictured it — the clear cuts put a bit of a lump in my throat, and the constant, gigantic log haulers barreling down the wet highway made driving a thrilling adventure,” Meyer wrote.

Before Forks was Forks, it was a prairie surrounded by forests. The area, 14 miles from the coast, was used as a hunting ground by the Quileute and Hoh tribes, who regularly burned the brush to replenish the ferns that fed the local elk and deer. White settlers arrived in the area in the late 1870s, setting up homesteads on land that the Quileute Tribe had unknowingly signed away in treaties 20 years earlier. (One of the main characters in the Twilight series, pining-for-Bella werewolf Jacob Black, is a member of the Quileute Tribe).

To early colonizers, the large trees surrounding the town were seen mostly as an annoyance. “They of course used trees to build things, but for the most part, the trees were hindering their farming activities,” said Baron, the Forks history buff. “So they cut the trees and used them and then tried to burn these gigantic stumps out so they could farm.”

Many Forks residents eventually recognized a more lucrative business opportunity in these lush old-growth forests. The logging industry started ramping up during World War I, when the U.S. Army was demanding high-quality Sitka spruce to build airplanes. A new railroad track provided a more convenient way to transport timber out of the remote town. By the 1970s, Forks was being called the “logging capital of the world.”

Around the logging boom years in the early 1970s, Baron started working in a hardware store in Forks that sold boots and other equipment. “People would come in from New York, all over the country, and you’d outfit them with the logger pants, shoes, everything,” she remembers. The newcomers would head out on the street the next morning and easily get a job. Her family has been in the town for three generations: her father owned a logging company, and her now-retired husband used to build logging roads. “Everybody worked in the logging industry until their poor bodies couldn’t take it anymore,” Baron said. “It’s a hard job.”

Forks’ logging legacy was interrupted by one of the biggest environmental conflicts in U.S. history, the so-called “Timber Wars.” For most of American history, forests were just a profitable crop, there for the taking — it wasn’t even questioned that people would cut them down to nothing. But then scientists studying old-growth forests realized that these complex ecosystems couldn’t just be replaced by planting some new trees after a clear-cutting. Some animal species, like the northern spotted owl, only lived in the Northwest’s dwindling old growth. Environmental activists started staging blockages and sitting in trees along the West Coast, trying to prevent the towering wonders from getting chopped down.

David Rolph, the director of land conservation at The Nature Conservancy in Washington, was studying the spotted owl in Forks during the height of the tensions in the late 1980s. He remembers driving from Seattle to his bunkhouse north of Forks one day and counting a full 76 log trucks coming the other way carrying old-growth timber.

“It was tense,” he said. “It was very much on the radar that spotted owls were becoming a threat to logging, so we were trying to operate under the radar doing our work.” They still came across loggers, many of whom felt attacked — Rolph summed up the prevailing sentiment as “we eat spotted owls for dinner” — but he says that some loggers understood deep down that the woods were getting overharvested.

In 1990, lawyers successfully used the threatened spotted owl to argue that Northwest forests needed to be protected under the Endangered Species Act, halting the constant hum of chainsaws across the region. Compounding loggers’ problems, there was very little old-growth nearby left to saw down. In Forks, mills closed, logging companies disappeared, and the unemployment rate climbed to 19 percent, according to state estimates. The logging industry wasn’t completely dead, but people moved into other jobs if they could, Baron said. The town is still dealing with the fallout of its key industry.

Then, quite unexpectedly, Twilight mania hit.

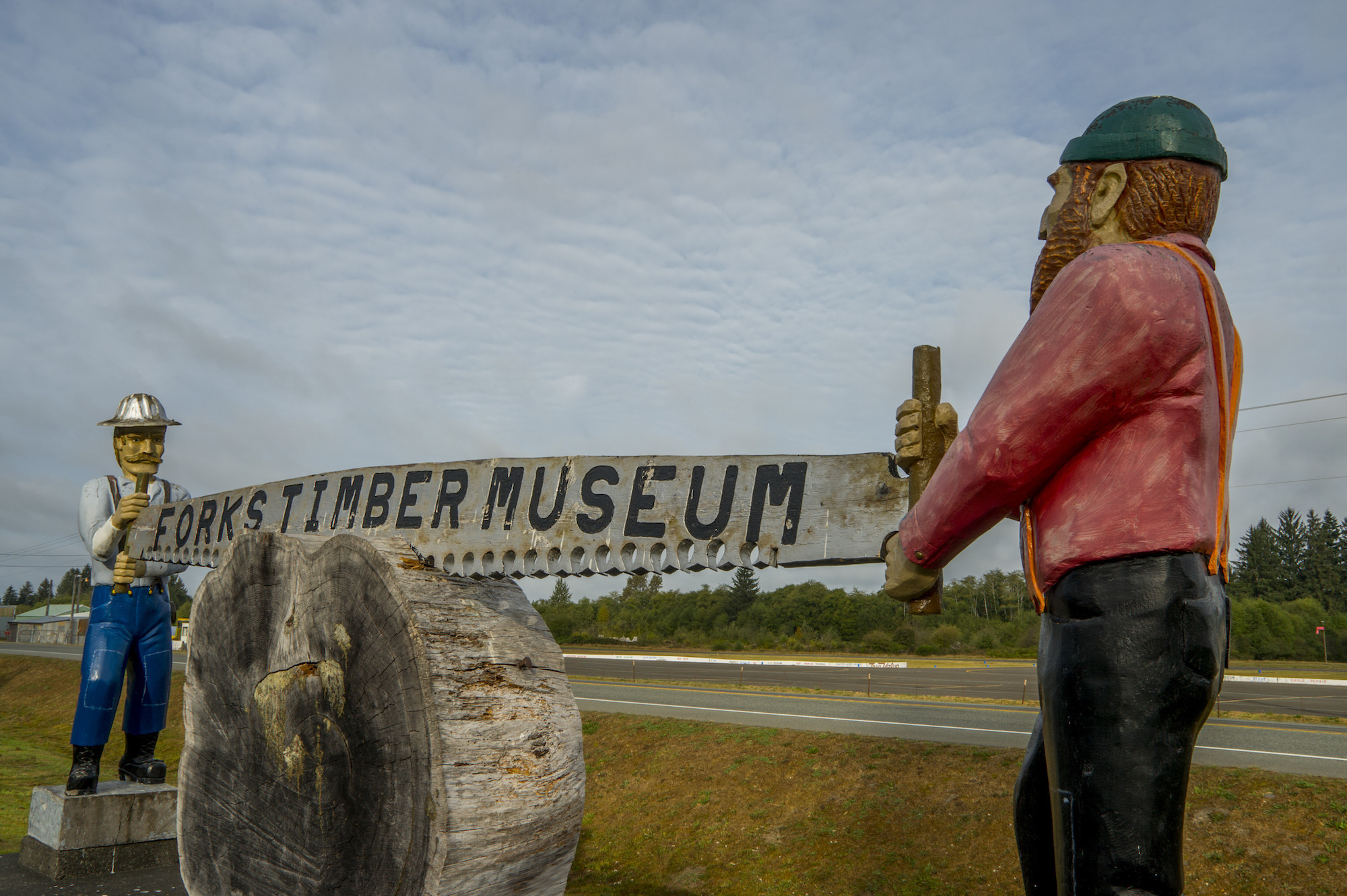

Twilight fans are greeted by a variety of series memorabilia as they enter Forks, Washington. Photos by Christina Horsten / picture alliance via Getty Images.

The town had never seen anything like it. There had always been tourists coming through Forks on their way to somewhere else, and the visitor center saw 5,000 people a year stop through right before the first book’s release. At the height of attention in 2009 and 2010, the number of visitors grew to an astounding 70,000 visitors a year. (Even in more recent years, that number has hovered around 40,000.)

As the force of Twilight’s fandom grew, the line between reality and fantasy started to blur — Forks started becoming more and more like Meyer’s version of the town. The visitor center hands out a “Forks Twilight Map” directing tourists to sites around town that are the real-life parallels of fictional Forks, including Bella and Edward’s homes, Forks High School, and even the community hospital (Bella, portrayed as a klutzy danger magnet, ends up in the emergency room frequently). A small resort west of town has a sign demarcating the “treaty line” drawn between the region’s imagined vampire and werewolf inhabitants, sworn enemies in the series. The annual Forever Twilight Festival draws people from all over the world, with a brigade of hired cosplayers paid to interact with fans and give them a taste of what it would really be like to hang out with Jacob Black, the friend-zoned werewolf, or Alice Cullen, Edward’s psychic vampire sister.

Environmental groups also recognized the annual descent of thousands of “Fanpires” on Forks as a new opportunity to rep their efforts to save the Olympic Rainforest. The Nature Conservancy, one of the world’s biggest conservation nonprofits, had started investing resources into the region around the early 2000s. The conservancy spent millions to buy up formerly logged forests around crucial watersheds, hoping to revive the complexity of these ecosystems and restore salmon habitat. These forests had been clear-cut and replanted, but often with just two species of trees spaced evenly apart.

Twilight fans had certainly brought with them a whole new meaning to the surrounding forest, which they imagined as teeming with vampires and werewolves. In 2012, around the release of the fifth and final Twilight movie, the marketing team at The Nature Conservancy in Washington had the idea of promoting the forests they were protecting as a “vampire refuge.”

“To the vampires and werewolves of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, the dark forests of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula offer the perfect habitat,” the press release read. It detailed the efforts of The Nature Conservancy, working with partners like the Quinault and Quileute tribes, to restore the lush, coastal forests and “bring back the giant trees where Bella, Edward, and Jacob frolic.” The news release was shared by more than 350 media outlets around the country and got 2,000 likes on Facebook. The campaign even made its way to the Jumbotron in Times Square, showing a picture of a young woman sitting in the cleft between two, huge, adjoined trees in one of the Olympic Peninsula preserves, according to Robin Stanton, media relations manager at The Nature Conservancy in Washington.

The Twilight-themed campaign brought attention to the forests and the need to protect them. But that didn’t necessarily translate to more cash to save the trees. “We didn’t really get people calling us up saying, ‘Oh gosh, I want to donate money to protect vampire habitat,’” Stanton said. “Our donors are much more motivated by salmon and trees and deer and bear and wolves and all of that. Vampires, not so much.”

A 20-minute drive west of Forks in the village of La Push, home to the Quileute Tribe — in the Twilight universe and in real life — attention from the series may have had a more concrete effect. For thousands of years, the Quileute Tribe had lived and hunted in a wide area, from the coast through the rainforest’s rivers to the Olympic Mountains. But treaties with the U.S. restricted their reservation to a small but picturesque area along the coast — just about one square mile — that’s vulnerable to tsunamis and the effects of climate change, like flooding.

Twilight helped bring national awareness to a border dispute over land taken by the U.S. in an 1856 treaty — land that Quileute leaders said they didn’t intend to cede. Congress settled the dispute in 2012 by passing an agreement transferring almost 800 acres of Olympic National Park to the tribe. (Indigenous stewardship can play a key role in safeguarding ecosystems and the climate, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has acknowledged, as Indigenous peoples have accumulated valuable knowledge about local forest and fire management over millennia.) In a PBS documentary soon afterward, Quileute Tribal member Ann Penn-Charles said that tourism and media attention from Twilight had bolstered the tribe’s long-running efforts to regain higher ground. “It helped us,” she said. “It helped us a lot, to push Congress.”

As for the town of Forks, most residents agree the Twilight movies were good for the local economy, with fan fervor kicking in right as the Great Recession began. “It’s a phenomenon that has pumped millions of dollars into our economy, and the economy of the Olympic Peninsula, I would imagine,” Andros said. But other community members caution that the benefits of tourism have been exaggerated.

“I just kind of grimace when I see the trope that ‘Twilight saved Forks,’” said City Attorney Rod Fleck. “Twilight helped economically, but I have a hard time saying that Twilight saved Forks.” The difference comes back to those lost logging industry jobs. The old timber- or mill-related jobs had better benefits and pay than their Twilight-related replacements. Fleck estimates you’d need two tourism-related jobs to make up the equivalent logging gig. That gap might help explain why so many people in the area are still struggling. According to the 2019 census, nearly 28 percent of people in Forks lived below the poverty line, more than double the rate in Washington state as a whole.

Whatever way you look at it, it’s hard to picture what Forks would look like today without the Twilight universe. “One of the things we’ve seen is a massive number of constant, repeat visitors,” Fleck said. When the fans started learning about the economic hardships people were experiencing in Forks, they donated diapers and baby clothes to help low-income mothers of newborns; they also brought in carloads of school supplies for local elementary schools.

“You couldn’t ask for a nicer demographic if you’re gonna get popular for something,” Baron said.

It’s been nearly a decade since the release of the last Twilight movie — plenty of time, by pop culture standards, for a fan base to wither and die. And yet, like one of its supernatural protagonists, the series’ popularity has arguably persisted beyond its natural lifespan.

The biggest misconception about Forks, Andros said, is that Twilight enthusiasm is on some kind of downward spiral. She says the town has seen recent bumps in tourism from last year’s long-awaited release of Midnight Sun, Meyer’s retelling of the first book from brooding vampire Edward’s perspective, and again from the recent renaissance of TikTok videos parodying the series. The release of the Twilight movies on Netflix this summer has revived interest even further, though it’s worth noting that they weren’t actually filmed in Forks, but around the Pacific Northwest, mostly around Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver, British Columbia.

As for Twilight’s environmental legacy, it’s hit some road bumps over the past several years. The Twilight saga itself doesn’t necessarily have an underlying environmental message, but that hasn’t stopped people from reading between the lines. Take, for example, the Cullen family’s decision to abstain from drinking human blood, instead satisfying their thirst with a vampire’s version of tofu: bears, mountain lions, elk, and the like, a diet that they jokingly describe as “vegetarian.” (“Of course, we have to be careful not to impact the environment with injudicious hunting,” Edward tells Bella in the books.)

But many critics have contrasted the book’s antimaterialist protagonist — Bella is perfectly content to wear sweatpants all the time and drive a red, beat-up Chevy truck — with the sheer amount of merchandise the Twilight saga has spawned: T-shirts, action figures, and even full-sized Edward decals to hang on your wall. One overzealous blogger even named Meyer “the worst ecological catastrophe of the 21st century.”

It sounds over-the-top, but during the height of the series’ popularity, making fun of “Twihards” and bashing Meyer had become sort of a national pastime. Sure, the series will not be remembered for stellar prose, a “strong” female lead, or setting examples for healthy relationship dynamics. But many of the people who once hated on the books and movies seem to have taken a softer stance in retrospect. YouTube film critic Lindsay Ellis said, in a popular 2018 apology video addressed to Stephenie Meyer, that the series wasn’t that bad in comparison to other pop culture works at the time — the vitriol that was levied against it was disproportionate to its flaws. So why was Twilight despised, while the Fast & Furious franchise basically got a free pass? “We — and by ‘we’ I mean our culture — we kind of hate teenage girls,” Ellis says.

Maybe there’s more to Twilight than people gave it credit for. The love story was powerful enough to capture the imaginations of millions and prompt hundreds of thousands of fans to visit a remote town in the forest. The annual Forever Twilight celebration in Forks kicked off some years with a “Vampire Habitat Walk” through the Hoh Rainforest or other parts of Olympic National Park, and sent fans walking down the beaches of La Push.

If there’s any environmental lesson that Twilight has taught its fans over the long-term, it’s that modern life has become too disconnected from the natural world. This is Bella’s realization over the series as well. At first, Bella hates Forks, disturbed by its moss-covered trees, abundant ferns, and the dreary mist. Meyer paints Forks’ supernatural inhabitants, with its outdoors-loving vampires and werewolves always speed-running through the forest, as more in touch with nature than its human ones.

But as Bella enters this supernatural world — eventually becoming a vampire herself — she sharpens her senses and becomes more attuned to the landscape. In the final book, Breaking Dawn, Bella takes her first romp through the trees as a powerful “newborn” vampire, finding that “the forest was much more alive than I’d ever known — small creatures whose existence I’d never guessed at teemed in the leaves around me.” She even worries, with her nascent rock-crushing strength, that she might accidentally hurt the trees if she’s not careful. In the end, Bella’s love story is more than the triumph of Team Edward over Team Jacob; Bella has fallen for Forks, her eyes opened to the beauty of the forest and its denizens.

It’s the Twilight romance almost no one talks about — one also reflected in the enduring real-life appeal of Forks and its surrounding forests, even beyond their supernatural associations. “We have so many people that have just come up for Twilight, but then they fall in love with the area,” Andros said. “And they do want to know more about probably the environmental aspect of it — you know, about the trees, about the tides, about the ocean, about the local tribes, about logging. So I think that that’s been probably the best thing, is it’s just opened people’s eyes and kind of given people perspective on what it really is like up here.”