Clothing, in our troubled modern times, is considered a fairly trivial thing. It’s incredibly easy to buy, wear, and discard without a thought. And perhaps in the face of climate change, the threat of nuclear war, and the persistent shadow of a global pandemic, cloth is comparatively inconsequential. But a new book and (perhaps unexpectedly) a television series about a post-apocalyptic America, offer a compelling philosophical counterpoint: the ways in which we make fabric have shaped our society and our environment, for better or for worse.

Let’s start with Sofi Thanhauser’s Worn: A People’s History of Clothing, which came out earlier this year. In it, she argues that much of the history of human conflict (and even climate change) is tied to the capitalist evolution of the textile industry.

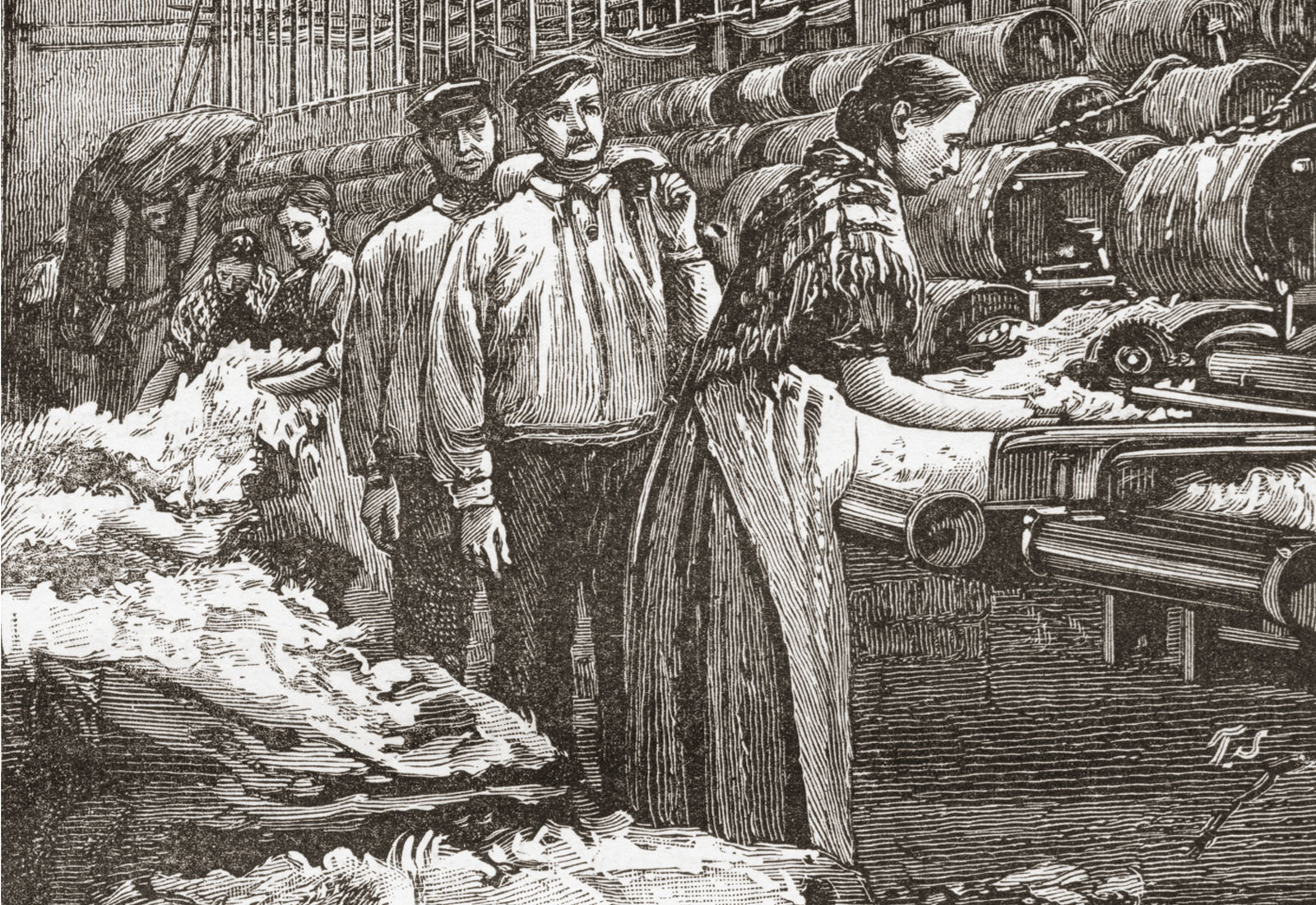

Worn begins with the meticulous craftsmanship of linen in the time of Shakespeare, a time in which even a modest, minimal wardrobe — having taken so many weeks to weave and sew — would be worth far more than the chest that contained it. From there, she takes us on a world-spanning tour of cotton, from the pesticide-drenched, water-sucking fields of west Texas to the sprawling factories of southern India. The journey is logically familiar: we made things painstakingly and by hand, and then we figured out how to make them with machines, and then we used those machines to exploit people for very little pay to manufacture huge quantities of commodities.

Much of Worn is really about labor inequity, the gap that arises when a handful of men are enriched through the misery of many. About a quarter of the way into this comprehensive tome, for example, she makes a rather eye-opening assertion: The Industrial Revolution” — that bête noire of all our current climate woes — “was a fabric revolution.” Cotton mill owners, textile executives, and silk merchants grow rich while those whose hands weave, sew, and dye the fabric itself live in pure penury. “Boosters of industrialization celebrate factory jobs as saviors of indigent rural women, without acknowledging that their poverty is a direct result of the destruction of what was once a successful and sophisticated textile culture,” Thanhauser writes.

This is a complicated argument that gets into the thrust of a very current debate: Why has widespread industrialization not relieved us of lengthy and onerous working hours? Few of us would be eager to return to days when we had to shear a sheep, spin its fleece into wool, and knit that wool into a sweater if we wanted to be warm in the winter. But it is not a controversial statement to say that the mechanization of clothing production has yielded great profits and improved the quality of life for some while simultaneously keeping many millions more in poverty.

This power dynamic has proven extremely difficult to overturn. In the rayon factories that sprung up in the Appalachian foothills at the beginning of the 20th century, the factory employees — almost all of whom were women and many of whom were teenagers — were subject to both extremely low pay and toxic fumes from carbon disulfide. The ingredient, used in rayon manufacturing, was so potent that it induced fainting spells on the factory floor. Thanhauser describes how in 1929, an organized strike of unionized workers in North Carolina found itself up against “the combined strength of industrialists, civic leaders, local law enforcement, the press, National Guardsmen, and the terrors of law enforcement” — and after days of brutal conflict, failed to yield any gains for the workers.

When you delve so deeply into the history of clothing production, it’s apparent that the fabric we drape over our bodies —- and the type of work that said fabric represents — covers a wide and overwhelming spectrum of issues indeed. The pedestrian objects that fill our daily lives can carry a heavy historical and ecological legacy acquired over the course of their production. But the life of those objects hardly ends as soon as they’re purchased. Since everything we have woven and stitched and knit will be part of our world for quite some time, so we may as well find purpose for it — a lesson hidden in plain sight in the dystopian HBOMax drama, Station Eleven.

Based on the novel of the same title by Emily St. John Mandel, Station Eleven tells the story of a society rebuilding itself after a devastating pandemic kills most of the global population in a matter of months. The survivors have to learn how to feed, clothe, and heat themselves in a world where you cannot simply buy what you need at a store because the supply chain has completely collapsed. While clothing is not the center of the storyline, it is a crucial part of the world that the series costume designer Helen Huang had to help invent. And so she found herself asking: If a future arrived in which we could no longer manufacture new clothing, what would people wear?

Huang said that she wanted the world of Year 20 — two decades years after the pandemic’s end — to feel “like a time capsule.” In her research for the project, she looked at what happened to clothing after it had spent years in a landfill, and was shocked to find how well most material that is considered cheap or low-quality today — synthetics like rayon and polyester and spandex — behaved like plastics, in that they were more or less immune to the elements. The costume team responsible for making the clothing look appropriately aged found that not even grinding stones would distress these types of fabric.

“There’s so much in our world right now that people can put on and wear – lots of things that wouldn’t age,” Huang said. “They don’t disintegrate, they don’t go back into the earth. So we tried to utilize that too, to describe something about this world [of Year 20]. Because in a lot of movies about the future, nothing of the past exists anymore, and that’s simply not true, because we’ve created so many items that would never go away.”

It also turned out that when filming the show in Ontario in summer of 2020, the COVID-19-induced lockdowns — apropos — greatly limited opportunities for costume sourcing. The only places that were available to Huang and her team were huge warehouses full of vintage and used clothes, the destination for millions of donated and deadstock garments. “We would be picking through them, and it accomplished a lot of the things I wanted visually for the show,” she said, “because it provided us with items that have actual memory, which you can’t really fake with clothing.”

Huang’s findings echo an anecdote from Worn’s foreword. In Martha’s Vineyard, where Thanhauser grew up, a town dump became famous as sight to scavenge for treasures thrown away by wealthy summer residents. Locals, including Thanhauser, would mine this trove of vintage designer throwaways and precious antiques to fill their own closets and homes. This is where the author developed an appreciation for vintage clothing, as she noticed how well the fabric and construction weathered the tests of time as compared to more contemporary mall offerings.

Both Station Eleven and Worn reinforce the fact that the fashion industry, with all its whims and waste, leaves more lasting marks on the world than one might realize. As Whitney Bauck wrote in a short essay for Grist on the lessons we can take from the supply chain interruptions of recent years: “What if we treated clothes shopping more like getting a new tattoo?” To expand on that, I’d suggest looking at every existing item of clothing as a monument: semi-permanent in nature, embodying both a great deal of work and probably some degree of human suffering, and a commemoration of the very specific era and place in which it was created.

Under this framework, there are no throwaway or worthless garments; there are only relics of the world we’ve created, and however flawed that world may be, they should be treated with care.