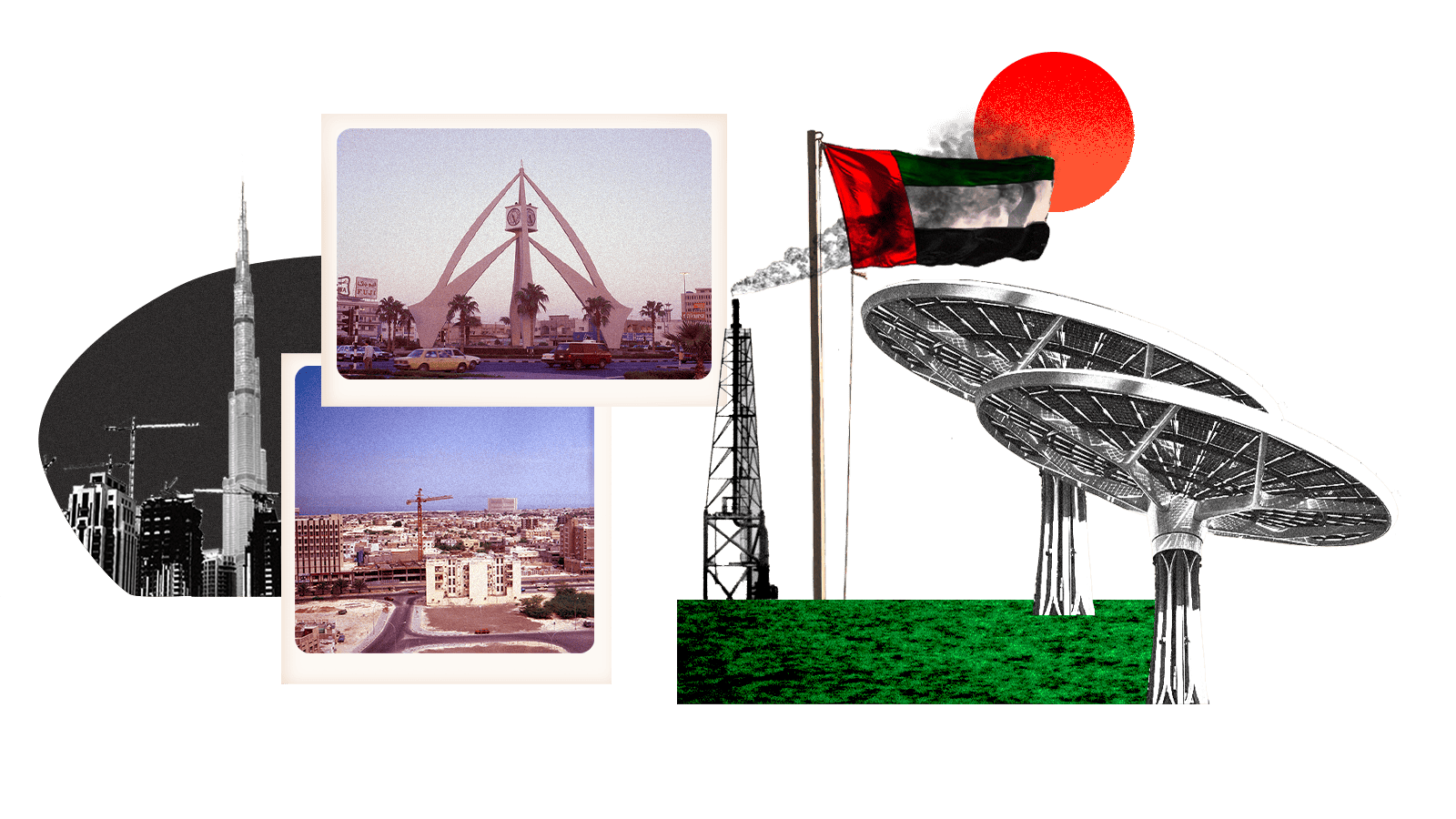

President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi of Egypt has worked hard to convince the world of his commitment to tackling climate change. His administration has overseen the construction of the largest solar farm on earth and sold the region’s first green bond for financing environmentally-friendly projects. This past May, he secured a deal with the German industrial company Siemens to build 2,000 kilometers of high-speed rail lines across Egypt.

Next week, leaders and prominent scientists from around the globe will gather at the southern tip of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula for the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference. The event, also known as COP27, is a big deal for the Arab world’s most populated country and the wider region, amid expectations that leaders of rich nations will be pushed to confront the consequences of their historic carbon emissions on the developing world. And it will also help Sisi promote the image of his authoritarian government as one committed to securing a more sustainable future for Egypt’s 100 million citizens.

But a closer examination of Sisi’s economic and environmental policies reveals an agenda marked by contradictions. In August, his administration announced a campaign to plant 100 million trees nationwide, but only after it had razed much of Cairo’s limited green space to build new superhighways. He has lauded Egypt’s water preservation programs, more vital now than ever as the Nile River shrinks, and in the same breath ordered that water be diverted from the river to construct a new capital city in the middle of the desert. More recently, the president came under fire for barring Egypt’s own environmental advocates from attending the climate conference.

Sisi has called the summit a “turning point” that will put the world on track to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, an amount experts say is necessary to avert the most disastrous impacts of climate change. But given his track record on climate policy and human rights, political analysts and advocates have questioned whether the conference is simply an opportunity for Sisi to boost his international standing and usher more funding toward a national modernization campaign that has less to do with the environment and more to do with his own entrenchment of power.

This year’s conference is “a very clear example of what greenwashing involves,” said Maged Madour, a political analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think tank based in Washington, D.C.. “From where I’m sitting, Sisi doesn’t give a sh*t about the environment. He’s not a green politician, he’s a brutal dictator.”

Sisi rose to power at a tumultuous time in Egypt’s history. When the Arab Spring broke out across the region in 2011, a popular uprising deposed longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak and threw the country into a period of uncertainty. Democratic elections were held, and Islamist politician Mohammed Morsi won by a narrow margin. His short-lived rule was marked by frequent power outages and economic turmoil.

When Sisi led the military coup that ousted Morsi in 2013, the public was desperate for some degree of stability. Sisi left his post in the Egyptian army to become head of the transitional government where he capitalized off this craving for normalcy, jailing more than 20,000 political opponents, dozens of whom died in police custody. It came as no surprise when he won the presidential election in 2014 with 97 percent of the vote (the same share the government said he received on his reelection in 2018).

Sisi got to work revamping the country’s power sector. The tumultuous years following the 2011 uprising were plagued by chronic blackouts, often in the searing heat of summer. For many Egyptians, those power cuts became synonymous with political instability. Sisi poured resources into developing three new power stations and tapping reserves in the recently discovered Zohr natural gas field. In 6 years, Egypt went from not being able to supply the country with enough electricity to selling its surplus to other countries in the region.

But the military general turned head-of-state did not stop at keeping the lights on. Early in his tenure, Sisi launched an ambitious plan to erect ostentatious new developments, from swooping superhighways and state-of-the-art bridges to a glittering new administrative capital in the desert, 50 kilometers from Cairo.

“It’s all part of this effort to reestablish the state as this engine of development,” said Michael Hanna, program director of the International Crisis Group, a think tank that performs research on global instability. He likened it to the modernization efforts of former president Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1960s, which saw the construction of the Aswan Dam and a suburb of Cairo, Helwan. “It’s a throwback to a different era.”

While the slew of mega-projects have garnered Sisi an air of legitimacy within Egypt and abroad, it has come at a stinging cost. Since they’ve been largely financed with foreign loans, the government’s debt has quadrupled over the past decade and helped push the country into an economic crisis. The Egyptian pound has fallen more than 40 percent since March, with the state heavily taxing its vast urban poor to avoid defaulting on its loans. Mandour said that helps explain why the president has spent the last several years promoting his sustainability initiatives abroad.

“He can borrow more based on that propaganda,” Mandour said. “The whole ‘I’m a sustainable green politician’ thing, that’s for the outside world so that they feel better about giving him money.” He used the example of Sisi’s decision to build a new high-speed rail connecting the Mediterranean to the Red Sea rather than rehabilitate the deteriorating train system along the Nile River, where 95 percent of the country’s population resides and fatalities from train crashes occur regularly.

Sisi has pushed for conversations around climate reparations to take center stage at this year’s COP. These discussions are expected to focus on whether wealthy nations with historically high emissions should compensate countries with relatively small carbon footprints such as Egypt for the economic losses they have incurred from climate change. Mandour questioned whether more funds should be given to support Sisi’s projects, which have done little to help the places hardest hit by rising seas, punishing droughts, and extreme heat.

Egypt’s long coastline, low rainfall levels, and densely populated Nile River Delta make it extremely vulnerable. Sea level rise has already uprooted whole neighborhoods in the fabled port city of Alexandria, and farmers in the Delta have struggled for years to break even as flooding and soil salinization diminishes their yields.

Sisi has responded by erecting seawalls and dumping thousands of tons of concrete on Alexandria’s beaches. While some farmers have since reported less flooding, experts have called the barriers a short-term solution that will only push the problem to other areas along the coast. Residents of some seaside neighborhoods have also criticized the government for forcibly relocating their families to austere housing developments where they are forced to pay higher rents than many of them can afford.

Omar Robert Hamilton, an Egyptian-British filmmaker and writer, told Grist that the government’s response to these challenges is more confounding when taking into account that it’s investing billions of public dollars in that new administrative capital in the desert. At a price tag of $59 billion, the city is Sisi’s most extravagant project yet. The plan is for the as-yet unnamed city to boast the tallest building in Africa along with a mega-mosque, a palatial presidential estate, and an Olympic sports complex.

According to the president, the new “smart city” offers a sustainable solution to Cairo’s overpopulation problem (the metropolis of 21 million is growing at a rate of 2 percent per year). But critics have questioned the legitimacy of the project’s green sticker, arguing that it will be unaffordable for the vast majority of Egyptians.

“What is sustainable about a new capital city in the desert filled with many million tons of concrete?” Hamilton asked. As other critics have pointed out, he believes the new capital is a way for Sisi to distance his government from population centers, fortifying it against public protest in case of another uprising.

Human rights groups estimate that Egypt currently holds some 60,000 political prisoners, many of whom are subject to torture and inhumane conditions. In 2016 alone, the Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms reported that its lawyers received 830 torture complaints and that an additional 14 people had died from physical abuse in custody.

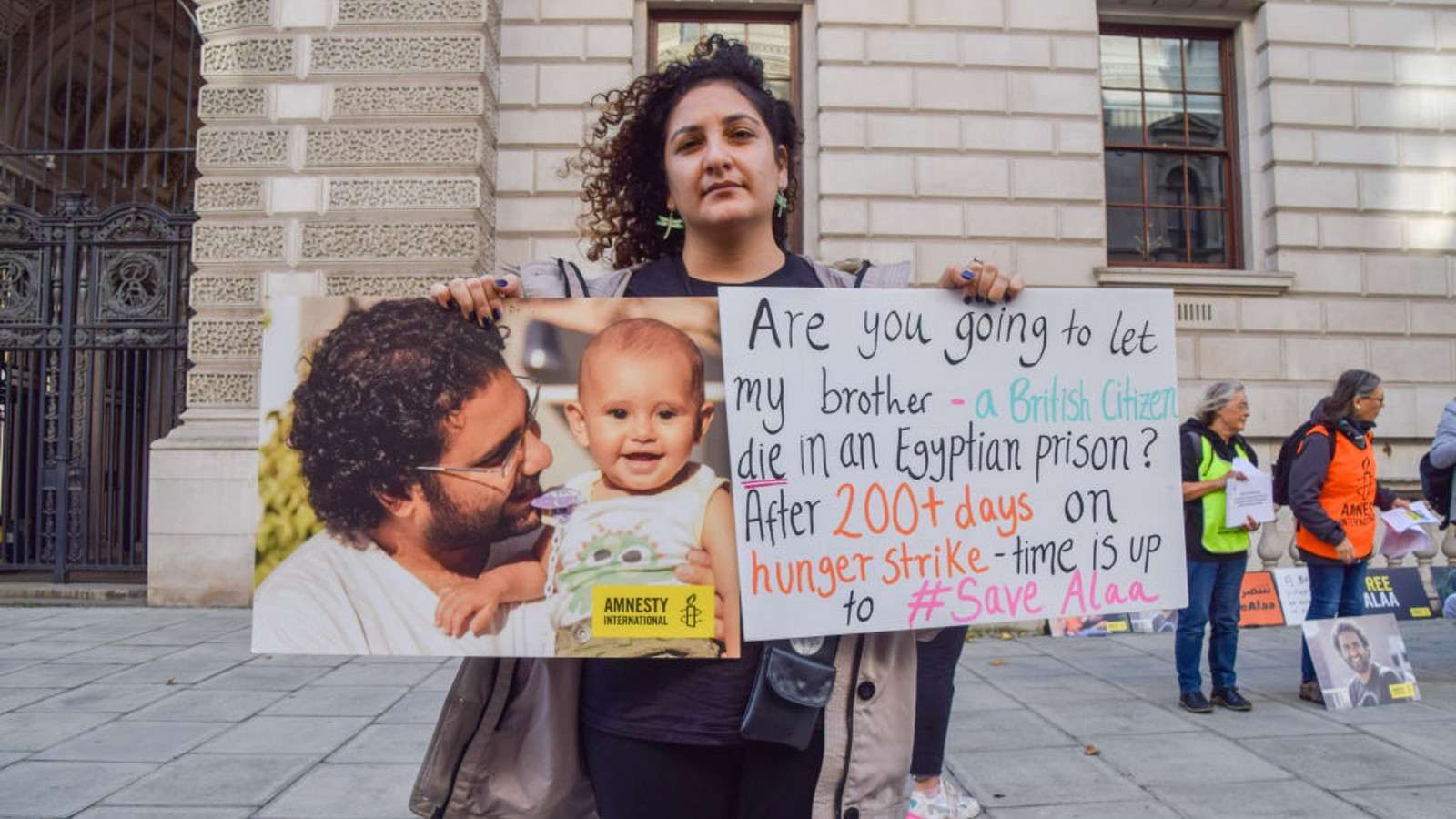

When he spoke to Grist, Hamilton was attending a sit-in in London for his cousin Alaa Abd El-Fattah, an Egyptian-British blogger, software developer and political activist who has been in and out of detention over the past decade. El-Fattah has been on hunger strike since April to protest being kept in solitary confinement and denied access to books, exercise, and contact with British embassy officials. El-Fattah’s case has attracted greater attention in the weeks leading up to the UN summit, as the international community pressures Sisi to confront his regime’s human rights abuses and allow Egyptian environmental advocates to participate in the conference.

“There’s a big international call for there to be a prisoner amnesty if Egypt is to be taken seriously as a partner in any kind of construction of a just future,” Hamilton said. “So we’re doing everything we can to get the UK to focus and push on this a bit in the next 10 days.”

Sisi fought hard to host this year’s COP 27 and bring the world’s most powerful leaders to Egypt. But hosting the summit has also attracted unwanted attention to the unsavory details of the country’s political system.

“It’s something that I think he did not anticipate but it’s happening anyway,” said Mandour. The high-profile conference “might be kind of a double edged weapon for him.”

Hanna, from the International Crisis Group, said that the unexpected consequences of hosting events like COP is what makes them interesting and potentially even influential after all the diplomats go home.

“The primary driver of [Egypt] hosting COP is not environmental policy. But these things take on a kind of life of their own,” he said. The conference is going to end, he added, and Sisi will have both enjoyed the international attention and endured the increased scrutiny of his human rights record. “And when everybody leaves, like what’s left? I’m interested in that.”