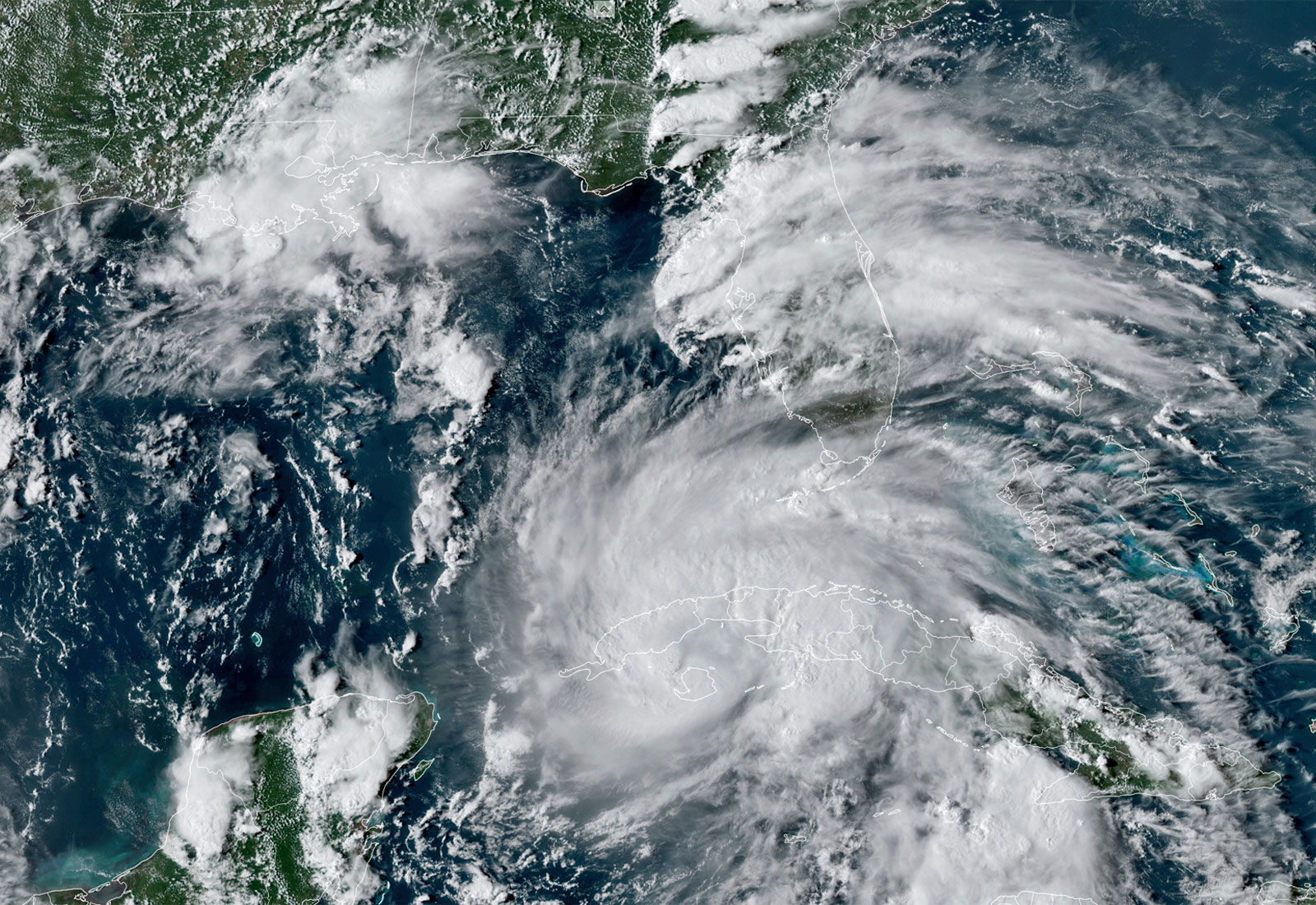

Less than a week ago, Hurricane Ida was known as Tropical Depression 9, a swirling mass of energy in the Caribbean Sea. That mass developed into a powerful tropical storm last Thursday, by which time there was no mistaking what would happen next: Ida was on track to become a major hurricane. Forecasters knew this with almost complete certainty for one simple reason: the storm was on track to pass through the Gulf of Mexico, where sea surface temperatures are unusually high.

Sure enough, Ida strengthened into a major hurricane over the Gulf of Mexico, gathering more steam as it moved closer to the coast over tepid water. It slammed into Louisiana near Port Fourchon on Sunday evening as a Category 4 storm packing maximum sustained winds of 172 miles an hour and unleashing as much as 20 inches of rain. Nearly half of the state was without power on Monday.

“Hurricane Ida packed a very powerful punch,” Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards said in a televised address on Monday. “She came in and did everything that was advertised.”

Climate scientists often emphasize that climate change doesn’t create hurricanes. Hurricanes are a naturally occurring phenomenon. Warming can exacerbate them though, often in devastating ways. That’s what may have happened with this storm, though Stephanie Herring, a climate scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told Grist that we won’t know for sure exactly how climate change influenced Ida until a formal attribution study has been conducted.

But Herring said that Ida exhibited behavior similar to previous hurricanes that scientists have conclusively linked to climate change, such as Harvey, Irma, Jose, and Maria, all of which occurred in 2017. Those storms were able to intensify quickly because of warm ocean water. “Ida seems to be consistent with these patterns,” Herring said.

Hurricane Ida developed into a Category 4 storm over the course of just a few hours, sucking energy from the bath-like water in the Gulf of Mexico. Surface temperatures are typically warm there this time of year, but parts of the Gulf are currently 3 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than they were, on average, in the late 1900s. That made Ida more intense more quickly — creating stronger winds than would have existed if Ida had skated over water that was cooler.

“Hurricanes almost always now undergo this rapid intensification before making landfall,” S.-Y. Simon Wang, a professor of climate dynamics at Utah State University, told Grist. “That trend is part of global climate warming.”

Climate change supercharged Ida on the front end ahead of its landfall in Louisiana, and it likely contributed to the torrential rain the storm brought with it as it moved inland. A planet warmed by anthropogenic climate change holds 7 percent more moisture in the air per degree Celsius of warming. That makes rain events much, much rainier, and it means more flooding for communities in a hurricane’s path.

“When storms rapidly intensify, they will be at a stage of absorbing more water because of the wind and all that energy, and when they start to dissipate, that’s when they dump all that water,” Wang said. “That can translate to heavy precipitation.”

Almost all of New Orleans is without power, one death from the storm has been confirmed with more expected, and thousands of buildings were damaged by Ida. It will take months for New Orleans and other areas affected by the storm to recover. But the Atlantic hurricane season is far from over. Meteorologists are currently monitoring three tropical disturbances in the Atlantic Ocean. Those storms are marked by climate change, too, whether they make landfall or not.

“All weather systems today are part of the global warming trend,” Wang said. “It’s like adding lemon juice to your water, it doesn’t taste the same anymore. Any hurricane that happens in a warmer climate will contain part of the signals of global warming.”