As COVID-19 spread around the globe this year, conspiracy theories did too. One wacky and pernicious standout claimed the new virus had been deliberately manufactured as a plot by a foreign power, or by billionaires trying to take over the world (or maybe even by aliens!). In mid-March, when the lockdowns were beginning, a survey by the Atlantic found that nearly a third of Americans believed that the virus has been created and spread for some nefarious purpose. If only there was also a vaccine that could fix the rampant spread of fake news.

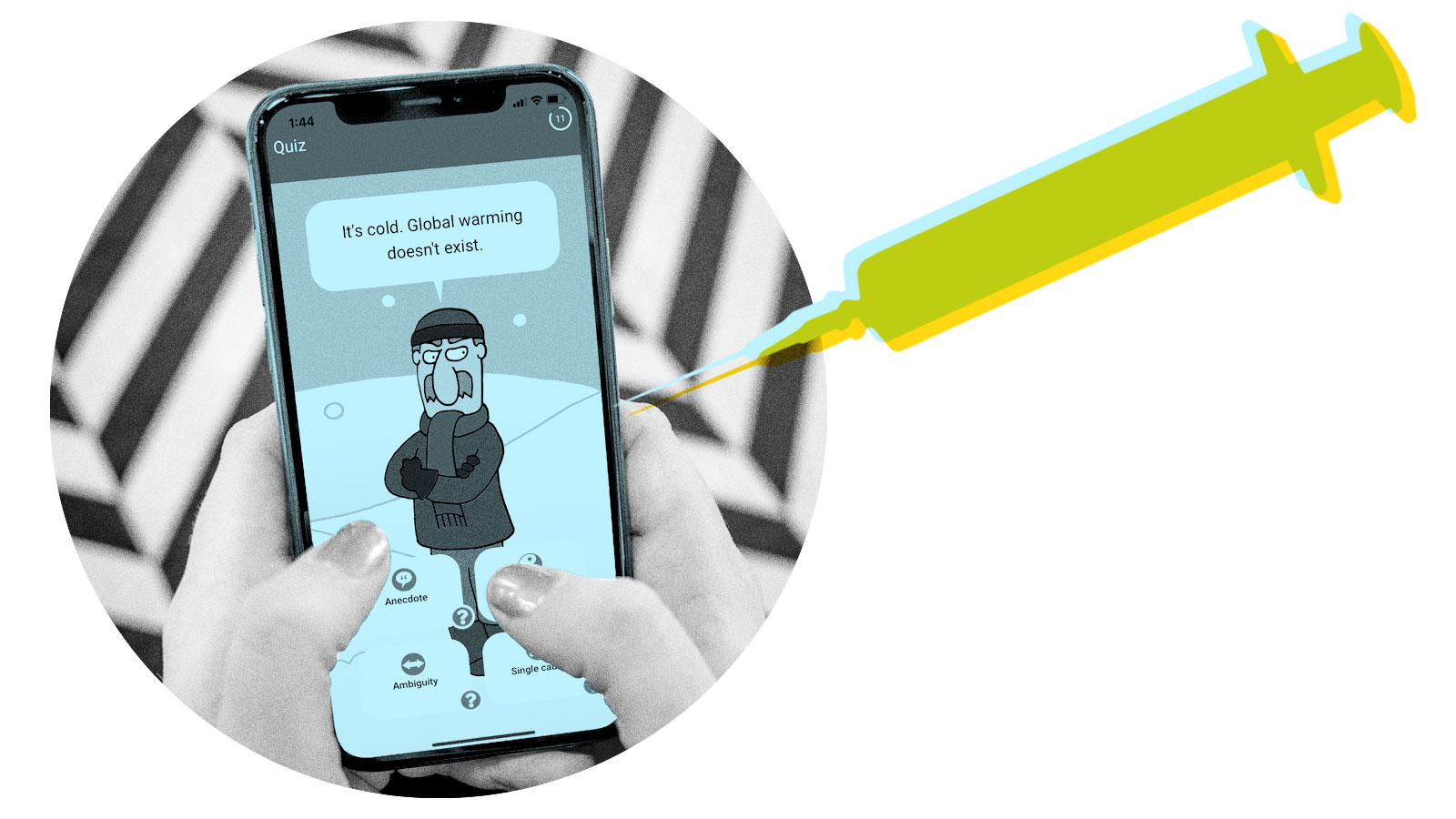

The idea isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. Research shows that exposing people to weakened doses of misinformation can teach them to identify it, similar to how a vaccine coaches immune systems how to deal with a virus. And instead of getting a shot, you get to play a game.

Cranky Uncle, an app released on Tuesday, uses this approach to teach people the ins and outs of anti-science propaganda — you know, the kind of myths that convince people climate change is a Chinese hoax. The game’s namesake Cranky Uncle is a cartoon figure that represents conspiracy-spouting uncles everywhere. He mentors you to become a science denier, just like him. He teaches you all about his favorite logical fallacies and the techniques he uses to dismiss scientific evidence, like impossible expectations (“Until we find all missing links, we can’t be confident in the theory of evolution”) and fake experts (“Relax! I have a bachelor in computer science!” says a cartoon doctor as he takes a saw to a very worried-looking Cranky Uncle).

As you giggle at silly jokes and learn how to rebut his arguments, Cranky Uncle gets crankier and crankier. Throughout the game, you get quizzed on your ability to spot logical fallacies and false arguments, improving your critical thinking skills.

Autonomy / John Cook

Cranky Uncle was created by John Cook, a cognitive scientist and climate communication researcher at George Mason University, in collaboration with the creative agency Autonomy Co-op. The app is now available to download for free on the iPhone App Store. Cook, who founded the popular climate myth-busting site Skeptical Science in 2007 and worked as a newspaper cartoonist for a decade, is also behind the game’s illustrations. He’s been an advocate for bringing humor and the arts into science communication and finding creative ways to reach people on an emotional level. “I always knew that cartoons had this potential to engage people about climate change,” Cook said.

The game is part of a new effort to “inoculate” people against fake news, sometimes called “pre-bunking.” Cognitive science and psychology experts say that the best way to address misinformation is to prepare people to identify it in real-time, as opposed to trying to debunk a message after it has spread.

Inoculation theory was developed by William J. McGuire, a social psychologist who got interested in the idea after the Korean War, when some U.S. prisoners of war elected to stay with their captors instead of returning home. At the height of the Cold War, many in government and academia were interested in how people could be so quickly indoctrinated and how to prevent them from getting brainwashed. Sander van der Linden, a professor of social psychology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, said McGuire’s research “showed that people are easily persuaded when they haven’t practiced their mental defenses against an attack, and you can bolster the defense by preemptively giving people weakened doses” of misinformation.

But over time, people forgot about McGuire’s theory. “It’s more relevant when there’s chaos in society,” van der Linden said. He rediscovered McGuire’s work about 10 years ago and realized that it was more relevant than ever in the age of the internet. He then helped develop three short choose-your-own-adventure games based on inoculation theory. In Bad News, an online game from 2018, you pose as a fake news tycoon, using fake experts, attacking climate science, and stoking fear among your followers. So far, the game has been played a million times. Playing it just once, according to a recent study, can reduce people’s susceptibility to fake news for three months. The idea is that in learning how disinformation is made and why it spreads, you can better spot it in the Wild West of the internet.

“The best way for people to learn is through experience,” van der Linden said. “I think everyone knows that intuitively. And that’s why it’s so hard to internalize a fact sheet, versus just doing it yourself.”

In Go Viral!, a collaboration between the Cambridge team and the U.K. government, you join the online group “Not Co-fraid” and spread emotionally resonant rumors about the pandemic. Van der Linden’s latest game, Harmony Square — developed with support from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, among other organizations — is about political misinformation during elections. You get hired as a “Chief Disinformation Officer” to “sow discord and chaos” in the fictional town of Harmony Square.

Social media companies recognize the promise of prebunking, too. Van der Linden’s team is currently working with WhatsApp on a fourth inoculation game. “If social media companies implement it, if the government implements it, you just reach so many more people, and you can have more public impact and more data,” he said. “We’re getting to the real-world stages of what used to be a theoretical idea.”

Twitter started “prebunking” for the first time this year to preemptively deflate myths about the November election before the voting started. “Election experts confirm that voting by mail is safe and secure, even with an increase in mail-in ballots,” one said. “Even so, you might encounter unconfirmed claims that voting by mail leads to election fraud ahead of the 2020 U.S. elections.”

Autonomy / John Cook

Cook says that interactive tools like Cranky Uncle are in demand from educators. So far, they’ve tested the game in high school and college classrooms across the country, including in West Virginia, Massachusetts, Texas, Utah, Washington state, and Washington, D.C.

If there’s a drawback, it’s that the mental defenses you develop by playing these games aren’t going to last forever. “In psychology, a lot of effects are temporary,” van der Linden said. So if people don’t practice the skills they learned, their ability to identify fake news may weaken over time. Like many vaccines, anti-misinformation defenses work better with a booster shot.