After decades of voyaging through galaxies in science fiction, William Shatner finally blasted off to space in real life last fall. Nothing could have prepared the man who played Star Trek’s Captain Kirk for the profound shock of seeing his home planet from 65 miles above.

When the New Shepard rocket capsule touched down in the dusty desert in west Texas on October 13, Shatner pulled aside Jeff Bezos, mega-rich tech lord of Amazon and founder of the private space company Blue Origin. As if in a religious awakening, Shatner described his 10-minute flight whipping through the layers of the atmosphere as an existential journey through Earth’s “comforter of blue” into the “black ugliness” of space. (“Was that death? Is that the way death is? Whoop and it’s gone. Jesus.”)

“What I would love to do is to communicate as much as possible the jeopardy, the moment you see the vulnerability of everything,” he told Bezos. “This air which is keeping us alive is thinner than your skin. It’s a sliver. It’s immeasurably small when you think in terms of the universe.”

In interviews afterward, Shatner made a plea for the planet as TV hosts tried to steer him toward topics lighter than death and global warming. The 90-year-old man, the oldest person to go to space, said humans can’t continue “burying our heads in the sand” about climate change, and that “we’re at a tipping point.”

The epiphany Shatner experienced is a phenomenon as old as space travel. Looking down on Earth from above for the first time, astronauts see that only a fine blue line of atmosphere shelters our planet from the hostile vacuum of space — and often, they suddenly get an overwhelming responsibility to protect it. National borders disappear; the scene evokes a feeling of cosmic connection. This so-called “overview effect” has been turning astronauts into environmental advocates ever since the first person in space, Yuri Gagarin, marveled at the planet from orbit in 1961. “People of the world, let us safeguard and enhance this beauty — not destroy it,” the Soviet cosmonaut said upon his return. A half-century later, ex-NASA astronaut José Hernández said that the view aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery in 2009 turned him into “an instant treehugger.”

In recent years, astronauts have become fixtures at international climate negotiations, bringing their big-picture perspective with them. In 2018, the former NASA astronaut Mae Jemison, the first Black woman in space, told delegates at the U.N. climate conference in Poland they needed a “reality check” on climate change. At last year’s summit in Glasgow, Scotland, known as COP26, French astronaut Thomas Pesquet called into the negotiations while orbiting Earth on the International Space Station, telling President Emmanuel Macron of France, “We saw all of California covered by a cloud of smoke and flames with the naked eye.”

There’s an irony here: In order to gain this more-than-sky-high perspective, astronauts and space tourists have had to take an incredibly polluting journey. Today’s renewed interest in space travel has revived environmentalists’ long-simmering antagonism against it, tracing back to the early days of the space program in the late 1960s. Space travel has been criticized, then and now, as a waste of money and resources and a distraction from more pressing problems. Some worry that the rejuvenated interest in private space travel might provide an escape for Bezos, Elon Musk, and other members of the super-rich, allowing them to take up residence elsewhere in the solar system and leave the rest of us behind on a burning planet.

Astronauts have countered that space exploration can go hand-in-hand with solving troubles on our home planet, leading to technological breakthroughs as well as fresh perspectives on environmental problems. More than half a century ago, the first photos of Earth taken from space inspired a mild version of the overview effect across the U.S. Those images eventually became a prominent symbol of environmental concern, plastered on T-shirts, tote bags, and bedroom walls. They’re widely credited for raising the public’s consciousness about the fragility of Earth and for helping shift a movement focused on local pollution to one that also thought “globally,” concerned with long-term survival on a finite planet.

Could today’s space mania help drive momentum for acting on climate change? Sending everyone into orbit clearly isn’t an option. But there’s now a push to try to bring the benefits of the overview effect down to earth, using virtual reality, for instance, to simulate the awe-inspiring experience.

The fact that so many of the planet’s 600 astronauts have turned into environmental activists — joining conservation groups, showing up at climate summits to cajole world leaders to take action — hints at the overview effect’s potential. The British journalist Lucy Siegle observed that astronauts are “rare in everyday life but abundant on the climate circuit.”

Nicole Stott, another retired astronaut who attended COP26 in Scotland, had always been aware of environmental problems, but seeing Earth from space on a three-month tour in the International Space Station in 2009 affected her in a profound way, she said in an interview with Grist. Her recent book Back To Earth pairs fun astronaut trivia (you can take a “shower” by “gently squeezing hot water out of the straw of a drink bag directly onto your body and watching it coat you like a second skin”) with facts about pressing environmental issues — climate change, microplastics, and the insect apocalypse. “I don’t know how you can experience something like that and not feel some change in you,” Stott said.

For nearly all of human history, people could only imagine what Earth might look like from far above, yet a surprising number of thinkers came pretty close to nailing its actual appearance. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato envisioned a leather ball with a bright “patchwork of colors.” In 1870, Jules Verne pictured travelers gazing back upon the Earth, a “delicate crescent suspended in the deep blackness of sky” with a shimmering blue atmosphere.

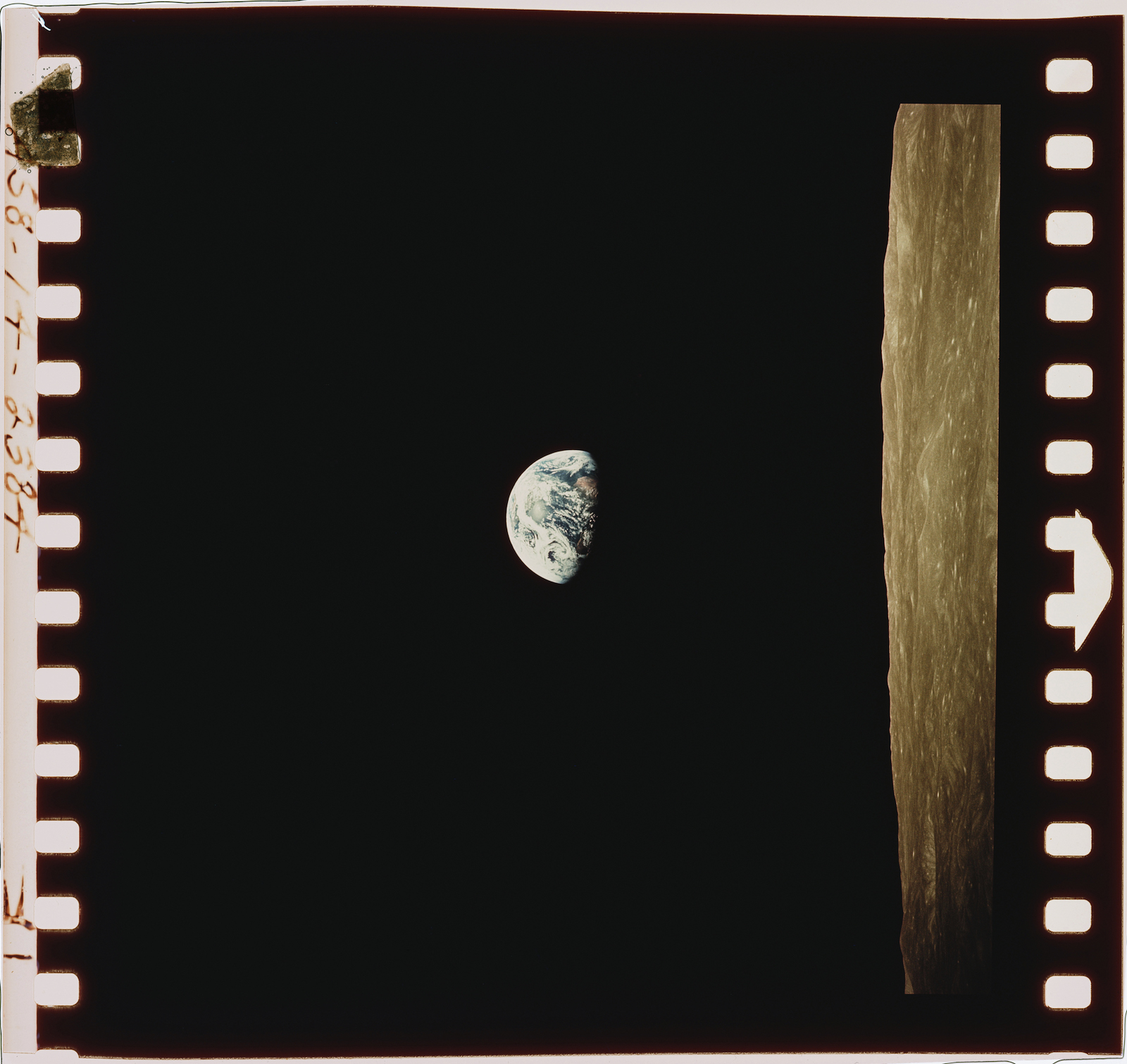

Knowing that the Earth is a planet, however, isn’t quite the same as seeing it with your own eyes. “Once a photograph of the Earth, taken from the outside, is available,” Fred Hoyle, an English astronomer, wrote in 1948, “a new idea as powerful as any in history will be let loose.” One of the first color photos of the Earth was shot by Bill Anders two decades later on the Apollo 8 mission on December 24, 1968. Now known as Earthrise, the iconic image was snapped incidentally, as the astronauts were supposed to be focused on the moon instead.

“When I looked up and saw the Earth coming up on this very stark, beat-up Moon horizon,” Anders later recalled, “I was immediately almost overcome with the thought, ‘Here we came all this way to the Moon, and yet the most significant thing we’re seeing is our own home planet, the Earth.’”

Those Apollo missions are often credited with providing inspiration for the environmental movement, as well as the first Earth Day in April 1970, when some 20 million Americans demanded that political leaders clean up the air and water in one of the largest demonstrations in U.S. history. Reflecting on his prediction, Hoyle observed that people suddenly seemed to care about protecting the Earth’s natural environment after the Apollo 8 mission. “It seems to me more than a coincidence that this awareness should have happened at exactly the moment man took his first step into space,” he said.

Others argue that it was a coincidence. Concern over pesticides and pollution grew over the course of the 1960s, after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring became a New York Times bestseller and a series of disasters caught the public’s attention, among them a fire on Ohio’s Cuyahoga River, where flames towered five stories high, and a drilling accident near Santa Barbara, California, that sent 3 million gallons of oil into the Pacific, creating a slick covering 800 square miles of ocean.

Some prominent environmentalists adopted the Apollo-era space enthusiasm for their cause. One was the Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, an influential counterculture magazine. In a 1966 campaign inspired by an LSD trip, Brand printed hundreds of buttons posing the question: “Why Haven’t We Seen a Photograph of the Whole Earth Yet?” (He got his wish in 1972, when NASA released the famous “Blue Marble” photo showing the Earth in full color, unobscured by shadows.) In the 1969 book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, R. Buckminster Fuller popularized the metaphor that Earth is a small, vulnerable craft hurtling through space, with limited supplies that crew members ought to manage carefully to survive.

The early photos of Earth from space, however, didn’t immediately become emblems of the grassroots movement, Neil Maher, a historian at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University, writes in the book Apollo in the Age of Aquarius. The first Earth Day relied on many symbols — dying trees, smog-choked skies, traffic jams, litter, and the gas mask, Maher writes. Instead, a photo like Earthrise was seen as a symbol of “worldwide harmony,” inspired by the words of Archibald MacLeish, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet. “To see the Earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats,” MacLeish wrote the day after Anders shot Earthrise, “is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now they are truly brothers.”

Looking back at how environmentalists viewed the space program in 1970, it’s no surprise that they didn’t readily embrace Earthrise. During the Gemini 12 mission in 1966, Buzz Aldrin spent more time on a spacewalk than planned, and had to dump equipment out of his capsule hatch to save fuel for his return trip. This kicked off a discussion of “space junk” in the press, with articles and political cartoons calling astronauts “litterbugs.” Some warned that NASA’s technology was polluting the Earth with rocket exhaust and industrial manufacturing. “Environmentalists and other critics are still attacking what they call ‘the talent and money-grabbing space program,’” the Boston Globe reported in 1970, just before the first Earth Day.

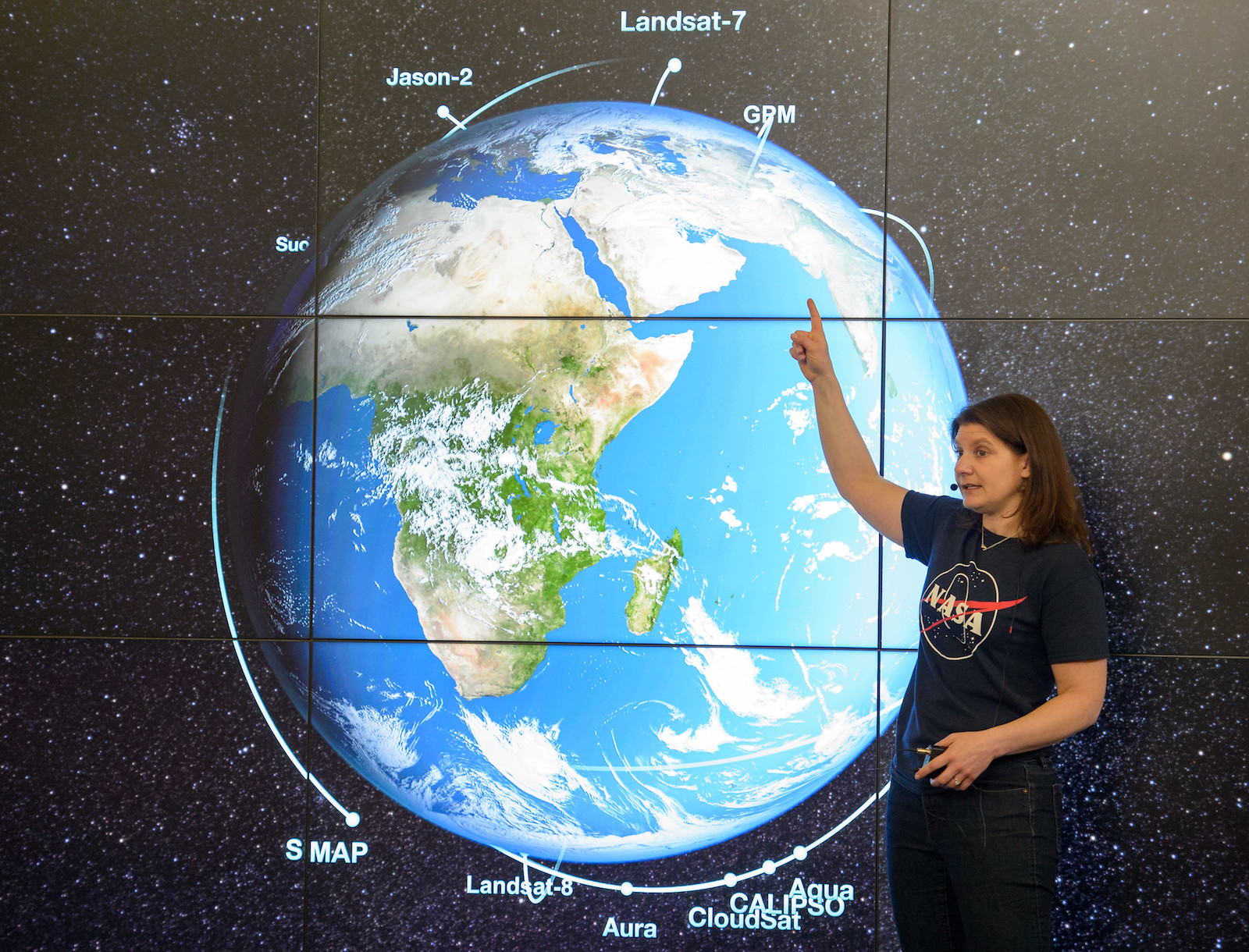

In response, NASA began positioning itself as an environmental authority, publicizing its new satellite technology that monitored the oceans, air pollution, and the ozone layer. “NASA is called the space agency, but in a broader sense, we could be called an environmental agency,” James Fletcher, the head of the agency, told Congress in 1973. “Virtually everything we do, manned or unmanned, science or applications, helps in some practical way to improve the environment of our planet and helps us understand the forces that affect it.” In the 1980s, NASA’s satellite data and computer modeling helped scientists track ozone depletion and global warming. It began to put this data alongside, or superimposed on, illustrations of the globe, reminiscent of the Blue Marble.

“While such images during the 1960s had symbolized global unity, NASA’s updated scientific versions instead communicated environmental concern regarding global problems including the ozone crisis and climate change,” Maher writes. By 1990, depictions of the planet had become a staple at Earth Day celebrations, appearing on flags and posters. It cemented the symbol’s new meaning and primed the public for an environmental interpretation of the overview effect.

Frank White, a self-described “space philosopher,” remembers coining the phrase “overview effect” during a cross-country flight in the early 1980s. At the time, he was working at Princeton’s Space Studies Institute, a nonprofit researching the possibilities of establishing human settlements in free-standing space. White spent the ride glued to his airplane window, wondering if the view from space would help people see Earth’s limits —“that what happens in one part of the planet affects the rest of the planet,” as he puts it.

He started talking to astronauts, asking them about their experiences, and discovered that he was onto something. “I’ve never met an astronaut who said, ‘What I got out of being an astronaut is, the Earth is not going to make it, so we need to go to Mars,’” White said. “They love the Earth more. They see the need to preserve it.” His book, The Overview Effect, came out in 1987. White thought that the book would spark a revolution in how people thought about space exploration, the Earth, and humanity’s place in the universe.

But the timing wasn’t right. The public’s fascination with space had waned. People had expected space tourism and a space station after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made it to the moon in 1969, but such feats were decades away. And confidence in space travel had been shaken. In 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger had exploded on live TV, killing all seven crew members, and NASA ended up pausing shuttle missions for a couple of years to reassess. White spent the 1990s talking at space-exploration conferences and interviewing dozens more astronauts, but the idea of the overview effect failed to go mainstream as he had hoped. “To be quite honest, for 20 years, I really thought I had failed,” he said.

Space is now cool again, thanks to social media, a widespread fascination with new technology, and the promise of private space tourism, hyped by an assortment of billionaires. Bezos’ Blue Origin is competing with Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic to send people into orbit, and Musk’s SpaceX aims to send humans to Mars — where Musk imagines people might one day live. Government missions have sparked enthusiasm too. The James Webb Space Telescope, a follow-up to the Hubble, recently settled into orbit a million miles away from Earth, with the aim of studying ancient galaxies, stars, and distant exoplanets in order to solve mysteries from the dawn of time.

There’s another similarity between today and the era of the moon landing. This coming December, the Earth and the sun will be in similar alignment as in December 1972, when the influential Blue Marble photo was taken during the final Apollo mission. In a post for The Conversation, Robert Poole of the University of Central Lancashire in the United Kingdom wrote that “space billionaires” should use the opportunity to update the Blue Marble shot and illuminate the differences between then and now. A probe could capture today’s planet from the same perspective, Poole said, revealing the ways the Earth has changed, with its expanding deserts and shrinking ice. “Seen side by side, these two Blue Marbles, taken half a century apart, would bring home the consequences of climate change wordlessly, instantly, and globally.”

So what exactly is this overwhelming feeling that space travelers get looking back at Earth, the one they struggle to put into words? David Yaden, a soon-to-be professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, describes it as simply “awe,” an overwhelming and complicated emotion triggered by a “perception of vastness.” That can be visual vastness, like how you feel peering into the Grand Canyon, or conceptual vastness, like the eye-opening feeling you might get watching a particularly insightful TED talk. Viewing Earth from space captures both types. “You’re seeing, all at once, basically everything that matters to us as human beings right in front of you,” he said.

Yaden studies how brief experiences, such as meditating or taking psychedelics, can cause long-lasting changes in people’s lives. He was surprised to learn that astronauts had this same kind of response when viewing Earth from orbit. “This didn’t exactly fit with the typical kind of trigger,” Yaden said. “I found dozens and dozens of accounts from astronauts describing these overwhelming feelings of awe and self-transcendence, as they reported feeling that this experience changed them for the better, and often in a lasting way.”

A decade after returning to Earth, Nicole Stott now finds herself thinking about the fragility of Earth and that thin blue curve of atmosphere every day. She has sought out activities, like meditation, that bring back that feeling of transcendence she felt in space. She has taken up “Earthing,” a practice of walking barefoot on the ground which helps her remember she lives on an actual planet. She’ll stand in the grass or dirt, thinking about the Earth spinning at 1,000 miles an hour and hurtling through space, and marvel at what a miracle it is to feel so comfortable, with the atmosphere holding “all the good stuff in” for our survival. “To me, that’s compelling, and I think it’s equally as compelling as looking out the window of a spaceship, if you open your heart and your mind to considering it,” Stott said.

Images of Earth from space have become so ubiquitous, she said, that they have lost much of their original charge. She hopes that technology can bring those images to life again, providing a taste of the overview effect for those who can’t afford a trip. A virtual reality series from Felix and Paul Studios, for example, filmed aboard the International Space Station, gives viewers an overview effect on VR headsets while they get a look at how astronauts live while orbiting the Earth. A Unitarian Universalist minister in Colorado, Jeremy Nickel, uses the effect in virtual meditations. Stott, herself, is particularly intrigued by SpaceVR, an attraction where participants strap on headsets and get in float tanks to take in views of Earth and experience zero gravity at the same time.

Yaden doesn’t think it’s possible to fully recreate the intense feeling of actually being up in space. At the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a doctoral student, there’s a lab that simulated shooting people into low orbit using virtual reality. “People definitely reported feelings of awe, but clearly at a much lower level of intensity than actually being there,” Yaden said. Shatner, for his part, noted that his brief but powerful space experience “wasn’t anything like the simulation.”

But maybe a dose of awe, spread across the population, could make a difference. Studies support the idea that awe might coax people into climate-friendly behaviors such as taking shorter showers, increasing the amount they’d donate to an environmental nonprofit, or making a personal sacrifice to protect the environment. In a recent review of the literature, psychologists at Carleton University in Canada looked at whether awe, compassion, or gratitude prompted by nature could foster these kinds of actions and suggested that the strongest case was for awe, though they urged caution about any firm conclusions.

Although most of us will only get a secondhand serving of the overview effect, Blue Origin, SpaceX, and Virgin Galactic will be ferrying more and more wealthy people into space, likely briefly. And that means more people will come to share that sense of awe that Shatner and former astronauts have professed. While that might seem like a bad deal for the planet, given the environmental toll of space exploration, advocates point out that in addition to generating inspiring images and valuable scientific knowledge, venturing into the beyond has offered some technological gifts to the environmental movement. Similar to how NASA greened its reputation with satellite monitoring, private space companies led by billionaires are also attempting to flex their environmental credentials. While a typical rocket launch can emit up to 300 tons of carbon dioxide, about 100 times more than a long-haul flight, Bezos’ New Shepard rocket runs on liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen — which don’t release CO2 when burned. Musk recently announced that SpaceX is launching a program to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere with the aim of turning it into rocket fuel.

Musk’s plan relies on untested technology, and there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of billionaires’ exploits in space. Still, as history shows, the environmental and space movements have been an inspiration to each other. The work and science being done on the International Space Station is, Stott says, about improving life on Earth: Water is heavy and expensive to transport, so astronauts recycle all of it, even their sweat and urine. The technology developed to clean water in space is now used to treat it in homes and industry — and as first-response equipment after natural disasters.

“In the grand scheme of things,” Stott said, “the return on investment that we have seen is significant in every area you can imagine.”