Themes make everything more fun, according to that friend who was always making you put on a costume for their parties pre-pandemic. Our newly elected president, Joe Biden, seems to agree. Possibly thinking some fun is just what the country needs right now, Biden dedicated each day of his first full week in office to a different theme, starting with “buying American” on Monday and racial equity on Tuesday. And Wednesday, it was climate day.

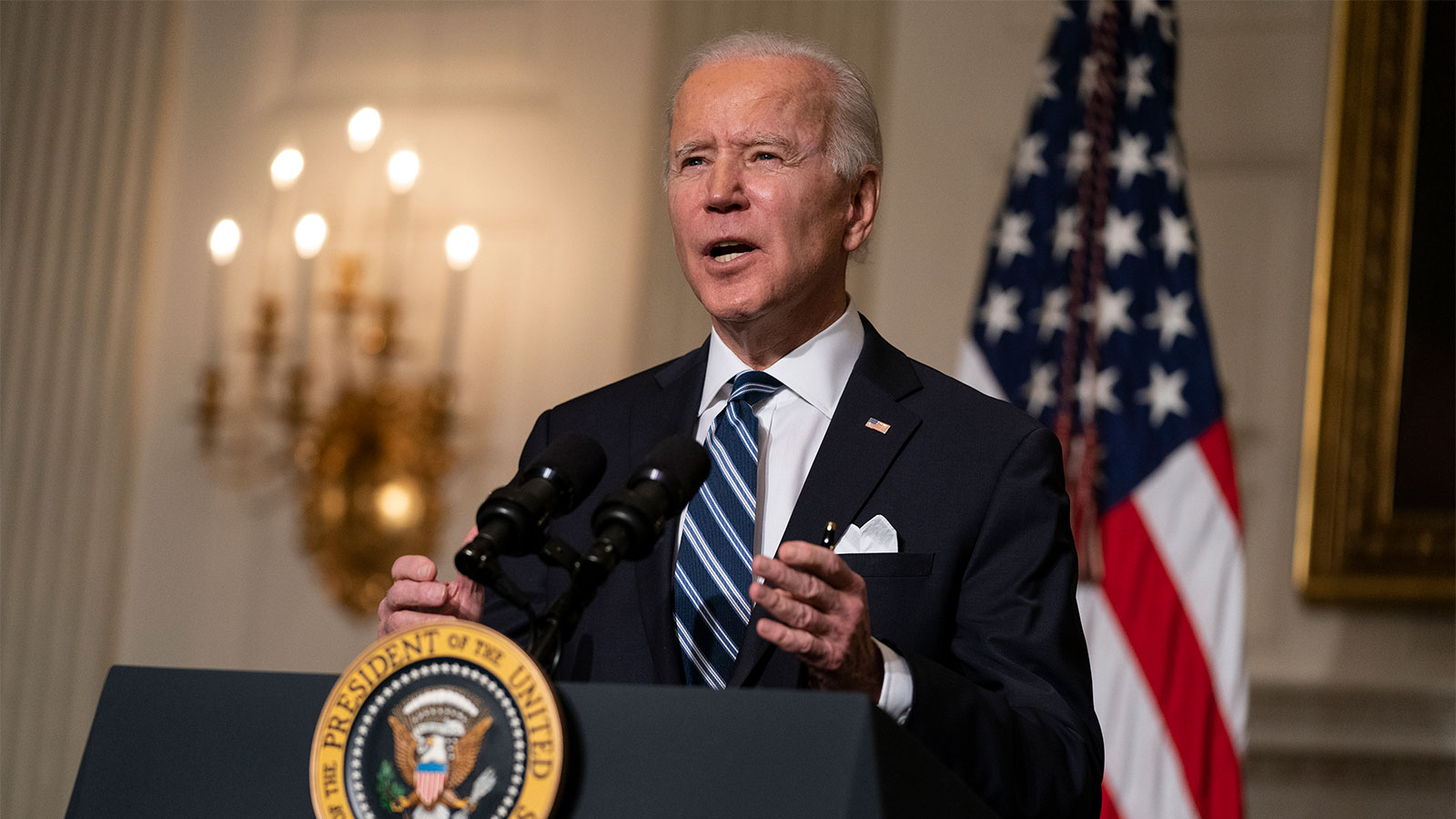

“We’ve already waited too long to deal with this climate crisis,” Biden said in a speech at the White House on Wednesday afternoon. “We can’t wait any longer. We see it with our own eyes, we feel it. We know it in our bones. And it’s time to act.”

Through two sweeping executive orders and a presidential memorandum*, Biden brought to fruition all kinds of promises he made on the campaign trail to address climate change. He directed federal agencies to stop subsidizing fossil fuels and to stimulate clean energy development. He hit the pause button on issuing new oil and gas drilling leases on federally owned lands and waters and requested a review of existing leases. (To be clear, that’s not a ban on fracking generally, which Biden can’t do unilaterally.) He hit the play button on developing a plan for the U.S. to fulfill its emissions-reduction obligation under the Paris Agreement. He hit fast-forward on getting solar, wind, and power transmission projects sited, permitted, and built.

“When I think of climate change and the answers to it, I think of jobs,” Biden said in his address before signing the orders.

To that end, he ordered all federal agencies to get behind the wheels of American-made electric vehicles and to procure carbon-free electricity. He kicked off research into how to pay farmers to sequester more carbon in their soils. He revived a conservation jobs program from the New Deal era under a new name — the Civilian Climate Corps — to plant trees, protect biodiversity, and restore public lands. Along those lines, he also pledged to conserve at least 30 percent of national lands and oceans by 2030, a nod to the biodiversity initiative known as 30×30 that more than 50 other countries have signed on to.

Transitioning to clean energy presents an existential threat to communities that rely on jobs and revenue from fossil fuels, and the order nodded to the idea of a “just transition.” Biden formed a new interagency group to coordinate investments in these communities and tasked it with advancing projects to clean up environmental messes, like abandoned coal mines and oil and gas wells.

The other side of a “just transition” is addressing the disproportionate health and economic burdens Black, brown, and Native American communities suffer from living near polluting infrastructure and in areas vulnerable to climate impacts, products of systemic racism. To that end, Biden took steps to put environmental justice on the agenda of every agency, including the Department of Justice. At the center of this strategy, he created an initiative called “Justice40,” which requires 40 percent of the benefits of climate-related spending to serve “disadvantaged communities.” (Which spending, which communities, and how these “benefits” will be measured have yet to be determined.)

And while Biden didn’t formally declare a climate emergency, as some activists had hoped, he did recognize the threat of climate change in another way. One of the orders elevates the climate crisis to a national security priority, reviving a memorandum issued at the end of Barack Obama’s second term that was swiftly revoked under Trump. To start, it orders Lloyd Austin, Biden’s secretary of defense, to prepare a risk analysis on the security implications of climate change.

Climate change has been called a “threat multiplier” in that it intensifies all other national security concerns, like economic and geopolitical competition among nations, political extremism, and food and water insecurity. In a recent op-ed, Sherri Goodman, who served as the first deputy undersecretary of defense for environmental security under the Clinton administration, gave several examples of how this is already happening around the world: Recruiters for the Islamic State are enlisting farmers who have lost their livelihoods due to drought. Drought is also exacerbating the poverty and the food insecurity driving migrants from Central America into the U.S. Fish are migrating too — into contested areas in the South China Sea, creating tensions for fishermen. In the Arctic, melting ice and permafrost are opening up new trade routes and creating a rush for resources.

“We need to understand better how to curb climate risk in the region, but also how that’s going to affect geopolitical competition, potentially with Russia, China, and others,” Goodman told Grist in an interview.

Requiring agencies to analyze national security threats through the lens of climate change could change how military resources are allocated and where foreign aid is delivered. It could also mean shoring up infrastructure in the United States to withstand extreme weather and sea-level rise. Goodman pointed to domestic threats like military resources strained by disaster response, bases threatened by rising water, and troops’ inability to train on extreme heat days.

Policymaking via executive order is a famously fraught endeavor, with orders vulnerable to legal challenges and subject to be overturned by a future administration. But even so, climate day delivered a lot at once, directing billions out of agency budgets to the cause — a fact that John Kerry, the new special presidential envoy for climate, acknowledged in a press conference on Wednesday morning about Biden’s climate plans. “But you know what? It costs a lot more if you don’t do the things we need to do,” he said. “It costs a lot more.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this post misstated the number of executive orders that Biden signed on Wednesday.