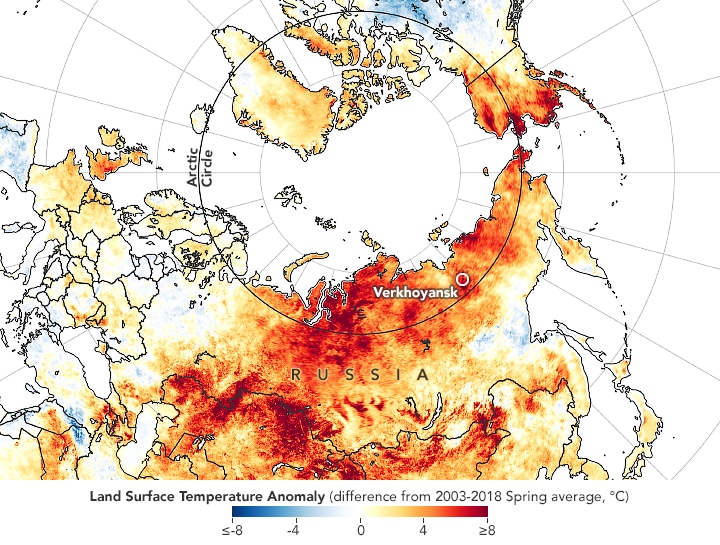

On June 20 last year, as much of the world stood at a standstill in the early days of COVID-19, temperatures in the Russian town of Verkhoyansk hit 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius). The heat wave lasted several days – amidst an already abnormally warm six months – drying out soils, baking vegetation, and helping to kickstart a number of large wildfires.

Now, the World Meteorological Organization, or WMO, has confirmed that the scorching temperature in Verkhoyansk that day set a new record high for the Arctic. It also prompted the WMO to add a new category to its international Archive of Weather and Climate Extremes, for “highest recorded temperature at or north of 66.5⁰, the Arctic Circle.”

The new record “is one of a series of observations… that sound the alarm bells about our changing climate,” WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement. Nowhere are these warning signs more pronounced than in the world’s polar regions. “In 2020, there was also a new temperature record (18.3 degrees C) for the Antarctic continent,” he said.

With the Arctic heating twice as fast as the global average, scientists expect to see record high temperatures shattered again soon.

In fact, 2021 came pretty close. In parts of the Arctic Circle, air temperatures measured 86 degrees F, while the ground temperature was 118 degrees F. Wildfires caused by dry and hot conditions this year led to the worst wildfire season on record for Siberia, with hundreds of fires catching across the region and smoke, even, reaching the north pole for the first time in history.

And all this warming in the poles has a compounding effect on climate change.

In the Arctic, last year’s high temperatures helped to spur a devastating fire season in 2020, with some fires burning even through the winter into 2021. Half of the area charred was peat soil, which contains high amounts of carbon. When the fires ravaged through the area, it released large amounts of carbon dioxide and methane, a greenhouse gas 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide, into the air. This in turn contributes to accelerated climate warming.

“Drier and hotter regional conditions under a changing climate have increased the risk of flammability and fire risk of vegetation,” Mark Parrington, a scientist at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, told the Guardian.

Scientists at the American Geophysical Union’s annual conference presented further evidence this week of just how rapidly the world’s poles are changing, this time far to the south. New satellite images from as recently as last month show large diagonal cracks across one of Antarctica’s most important ice shelves. The instability indicates that the shelf could melt in the next five years as ocean and air temperatures rise, the scientists warned.

If the shelf were to melt, it would cause the Thwaites Glacier, a Florida-sized piece of ice, to flow three times as fast toward the sea. Some believe the Thwaites Glacier, also known as the “Doomsday Glacier,” is on an irreversible path to collapse, which could raise sea levels by as much as 10 feet. It already makes up 4 percent of global sea level rise.

Ultimately, the new data shows that the threat of the shelf melting is closer than previously thought, and could result in sea level rise of several feet, putting millions of people in danger.

One scientist, Erin Pettit at Oregon State University, told the Washington Post that looking at the images of the cracking ice shelf, it was “hugely surprising to see things changing that fast.”

Another, Twila Moon, a glaciologist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center told the Washington Post, “the very character of these places is changing. We are seeing conditions unlike those ever seen before.”