This story is part of Imagine 2200: Climate Fiction for Future Ancestors, a climate-fiction contest from Grist. Read the 2021 collection now. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

* * *

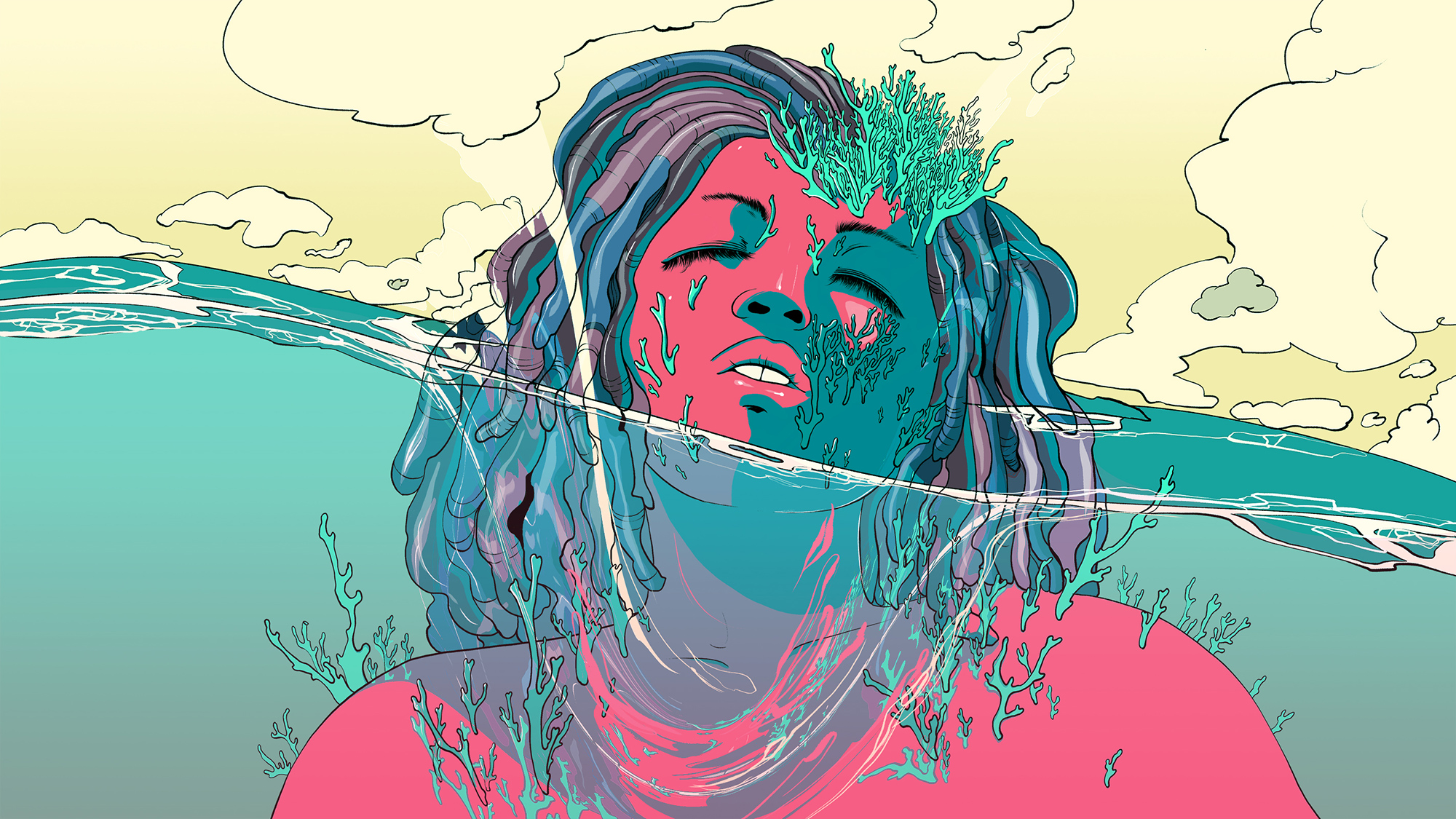

The coral could no longer tell her apart. Her breathing had slowed and so had her body. She knew she was running out of footsteps. A decade of walking would do that to a girl like her. The sand could sometimes catch her heels, distracting her to memory. Getting lost in who she once was and forgetting what she was becoming. That’s how the stillness found her. Surrendering to the glimmers of a life above the water. Her life before the water. Quiet. Alone. Broken whenever the current breezed through her, its chill seizing her neck and voiding her pores of plankton, algae and grit. Cold enough to remember what real wind feels like. Standing at the peak of some hill — what was its name again? Farnham? Or was it Felicity? No, that’s just what she called the feeling. The name didn’t matter. What mattered was the breeze. The mournful sigh of the Atlantic washing over her, only ever heard in branch rattle and casuarina shivers. And she could hear them. Each green strand swept up in 1,000 breaths of wind and all its loosest fruit dropping from the sky like an emptied nest of sea urchins. She was careful never to walk barefoot under casuarina trees. The unwary shock of their fruit under heel could feel like glass thrust into bone … like lionfish barbs … the thorns of a blowfish … stepping on the fangs of a reef — the wind! Remember the wind! She can’t afford to drown herself in similes. She must remember the wind. The wind cutting through her shirt. Sharp enough to remember where her nipples were. Are. Not polyps. Nipples. The ones she grew on purpose. The ones that were hers even before the changes. The changes in her body and the changes in her world. She could no longer tell them apart. The wind picking through her hair like casuarina. The Atlantic sighing with her. Staring out over that hill without a name, everything could be her. And she could be …

The current broke through. It reached into her and she remembered. She remembered where she needed to go, and she could once again pluck out all those questions that waited for her. How many days had she lost? How many footsteps did she have left? How long had the stillness claimed her? How much of her was still there buried beneath the coral? Her polyps could choke from these kinds of questions. Better to let them be carried away on the leftover gust of currents. Better to just keep moving for as long as she could. As long as her mind could outgrip the coral. How much farther was it? She tried to look through the black thicket of saltwater. Any soreness would be softened by her second eyelids. She stared because she needed to know where she was. She needed to remember. Her neck hissed like shoreline avalanches when she turned to face the nearest landmark. Once, a supermarket. Now, a ruin brained in coral. Elliptical stars bloomed throughout the darkness. A colony of hungry mouths to feed … She never wanted to be that — a colony. She wanted a family, sure, but not whatever this was. Rooted and bound to your species. Repeating and repeating an ideal body. An ideal mind. Not allowed to have your own thoughts. Never able to see further than the horizons of the colony. No, she always wanted more than this. More than this place. More from this place. The coral stared back at her like it knew these wants would all be in vain. Like it knew that all that would ever grow in these waters was colonies. Her feet slipped into roots. It had found her again.

“That’s your son?”

With a little flirt in his smile, her father lapped up this bait thrown by the checkout clerk.

“My eldest.” He let his daughter die in his mouth.

Floating her palm a little lower than the counter, the clerk patted the head of a ghost only she could see.

“I remember he did small so.”

She never understood why the only changes people seemed to smile at were height and age. Grow tall, not wide — a rule she would need to outlive. Lest she hear some malicious auntie or some ugly-on-the-inside family friend proclaiming their disapproval, “Yuh get fat.”

Floating her palm a little lower than the counter, the clerk patted the head of a ghost only she could see.

Never a surprise to them. Just a disappointment. That her body could grow so unruly and out of line. She couldn’t understand why stepping out of line had to mean stepping into harm’s way. Neither the checkout clerk nor her father could see the newfound softness of her shape, skin, and hair. Nor did they notice the tasty shiftings of her fat. Between her welling emotional depths and all that sweetlike-Demerara joy she was living, none of it could be registered. They just didn’t know what to look for. Too busy remembering a child who wasn’t there. Too preoccupied welcoming a man that would never arrive. And so of course they couldn’t see the changes. The ones that mattered. The ones that would keep mattering.

She stayed silent. Just idled away the moment, fattening her strung-out backpack with groceries. A monotony of cans broken only by a few standout treasures. Saltfish. Hot pepper. Cucumber. Everything piling up, the mouth of her bag hung agape in horror. She lost herself in the wafting foulness of breadfruit, left behind from some acrid gully. It was still cupping a haunting of crushed ants, wet grass, and the far-off stink of freshly dead fieldmouse. But this was, she knew, the way to pick breadfruit. It should smell like it’s rotting from the inside-out. After all, what they call yelluh meat is just a ripening dressed in decay. When the flesh falls apart, sweet and off. Just like her. Yelluh meat — what both men and women searched for buried in her thighs. Something discoloured from race and so debased it didn’t have a gender. All the most sumptuous changes had smelled like something dying. And something dying could taste like heaven. And they knew that, the men and women. So, they craved her. They craved her centipede-bite lips and her little coucou-scooped breasts. She was loose wet sand. Sticky where it mattered, but never fully graspable.

Locking the teeth of her backpack, she rushed ahead of her father. She needed to get away from the distracting scents of dead boys and breadfruit. She needed some air. They still hadn’t noticed her, and on today of all days. Her sixth month on estrogen and they just couldn’t see it. All that moved within her. And, in the beginning, maybe that was the point. To touch this change invisibly. To transform before their very eyes, hidden in plain sight. Each day, she’d let it melt into her. Let it drop below the surface. The ripples it would leave behind moved with the kind of slowness and subtlety that had kept her undetectable. She could hide herself in raindrops. And with each day, she would feel a little bit different. It could hardly be measured except for maybe that singing tingle in her nipples and a fresh clinginess from the grasp of her shirt. She felt a little bit softer and she walked with a little more rhythm — and she didn’t think that was chemical. She just felt happier to hold her own narrative again. Lighter, now that her drowned life could find another kind of breath fluttering below the surface. Maybe it was chemical. A pill that let her breathe underwater. And for a while, that metaphor could be real enough to float on. To walk on land unscathed. Unscathed enough, at least. Disappearing when she needed to, deep into the body of a man who lived in the eyes of others. His skin would keep her warm, moist, and breathing. And she would do what she had to. She was not prepared to drown. Not here. Not like this.

Outside, the sun had no mercy to spare. Limestone and construction dust choked the air in white. The street was arid and thick with noise. No room for softness here. Jackhammers razed the ground to powder while minibuses feted down the road. Car horns screamed aimlessly to the sky as if God Himself would divert the traffic. Dorian was coming and he wasn’t playing. His was the only name worth remembering. Everyone was bracing themselves with groceries. A hoard of plastic bags bursting with dry food and cans. People buying up all the provisions they could carry. You’d think the cans were filled with hurricane repellent. Out on the pavement in front of the supermarket, she stood in the middle of it all. This storm before the storm. Soaking it in, she let what little breeze there was tickle her hairy legs. From her washed-out, ashy denim shorts, a line of sweat painted itself down her inner thigh. Beads of terra-cotta skin poking through the moth-holes in her shirt, hoping to catch this excess of light.

She was staring off toward the entrance. Keeping guard of this precious moment where she could just stand in her body and not be seen otherwise. By her father or by anyone else for that matter. A plaster arch sheltered the doors. It was dressed without a soul in a sandy hue of magnolia. The whole building actually, except for its navy, orange logo. Altogether, it looked like someone who hated sunsets painting with their colors. It was meant to read simple and stylish. For the tourists, whose tastes were first to serve. The central supermarket for the resort district. What an eyesore. She recoiled. A magnolia storehouse heaving with burnt salmon bodies. She always wondered how they managed to get so red while still stinking of sunscreen. But this place wasn’t for them today. No one could afford to think about tourist dollars when there was a hurricane to shop for. She lowered her eyes on those she called her people. The automatic doors opened and closed like a panicked heartbeat. Families pouring through with children hanging on each arm. They all firmly believed survival was something you bought in a store. The only belief more unshakable was thinking God was from this island. As far as they knew, His navel string was buried here and deep within every one of them. They could never accept that God had left with the British.

This is what she loved doing. Vanishing into the lives of other people. Her people. Taking a highbrow pity on them to avoid the reality that she and they were so painfully bonded and alike. She never really belonged in other ways. So, she loved them difficultly and from afar. Mostly with complaints and criticisms. She wanted more from them. For them. But she loved it. This game of pretend in moral superiority. Nestled in her judgments, she felt unseen and therefore invincible. She was never waiting for her father. No, she was savoring this joy untethered from looks that never knew how to read her. Spreading herself wide in the world in those seconds before his return. Bleeding out among all the noise, thinning into dust, burning with the sunlight, and drifting on the breeze. She knew how to be everything when nobody was looking.

A handful of polyps crumbled from her eyelids when she finally came to. All of her panicked for a second, trying to catch her breath too fast through every living pore. Which body was she in now? She patted herself down. No moth-eaten shirt. No denim shorts. Just rubbery brown skin oozing with curls and coral. Her memories could be dangerous. Fatal, even. And right now, she couldn’t afford to be disembodied from the present. The past was underwater and she didn’t want to drown in it. Not again. Turning her back on the coral colony, she kept moving. A little farther uphill and she would have made it. Keeping the distant past bubbled out of mind, she stayed with the road ahead and her life below the surface. The trouble brewing in her body could sometimes soften when she let the beauty of this world shine on her in wonder. And it was a resonant beauty. One that made real sense to her. Drowned, fragile, and in parts, ruined. But full of the promise of life. And life that lived together. An interconnectedness she couldn’t easily remember. Surviving independently not beside but with each other. Rainbows of shrimp nursing anemones. Anemones protecting their tenants from harm. Coral and algae living in close quarters. Keeping each other alive. Caring for each other’s bodies like we lived in each other’s bodies. She always smiled when she saw this. It was all so foreign to what she remembered before Dorian. And she would smile harder knowing that life here lived everywhere. There were no empty enclosures. No annexed lands. The road was lined with sunken villas. Forever vacant in the past, now swarmed with coral and peopled by fish. Everything grew where it could. No permission needed. Just a fighting chance and a helping hand, fin, claw, tentacle, or polyp.

A handful of polyps crumbled from her eyelids when she finally came to.

Villas started turning into the remains of chattel houses as she continued up the road. Trying to find the sun, she looked up to the surface ceiling above her. It was cloudy with sargassum. Forests of amber seaweed as thick as an eclipse. She could make out little pockets of sunlight whenever the clouds parted with the waves. The surface had always been restless, just as everything beneath it. She convinced herself that as long as it kept stirring, so would she. She didn’t really have a choice. The restlessness had held her ever since that day. Like a dead body washed ashore from aimless days of drift, the news came running on the water. A Vincentian fishing boat spotted it. Rising from the sea, a mound of sand and limestone struggling to stay afloat. It wore a crown of dead black trees. A giant sea urchin. That’s how the fishermen described it. The humble peak of Mt. Hillaby, which was nothing more than a slope of dirt and bush, poking out of the water like a bobbing skull. All that was left of her island and she was determined to see it. She was born there and she would die there. Everyone else had died there. Those who found life below the surface — her and the other girls — they were never really living in the first place. Her people had made sure of that. When the water came and left her people for dead, she got stuck in the loop of a question:

“How do you grow up on an island without ever learning how to swim?”

She asked it without judgment. It was something driven by a child’s curiosity. Knowing how to swim wouldn’t have saved any of them — she knew that, of course. Nobody could outswim a hurricane. Yet the question still troubled her. Every time there was a drowning, the island would swell in grief. Local and tourist alike had been claimed by the sea, but death never seemed to play fair when it came to the lives of her people. From this, she reasoned that death must be a tourist too. That, or a hotelier. She knew how her people got here. It wasn’t a secret for her generation. Ships brought their ancestors in all kinds of chains but she didn’t think any more sense could be wrung from that journey. That is, any sense that hadn’t already been written to death. That hadn’t written her people to death over and over and over again. Why would she rub manchineel in her eye in the hope of understanding it? And after all that senselessness, this little rock of horrors, trembling in the Atlantic, suddenly had to hurtle itself into a society. That question again making her seasick: How do you grow up on an island without learning how to swim? Its shadow mocked her and her people. Why would property need to swim? Where would it need to swim off to? She grew suspicious of the drops of white in her that made these questions all too easy to imagine. She feared her blood for what it could want if hers was not the body to hold it. She tried to salvage something from the wreckage of that journey.

“Who the hell would want to swim after all that horror on the water?”

It still wasn’t enough to soothe her. She couldn’t leave her people stranded there like that.

She looked to what was left of all the chattel houses that used to hug the road too tightly. There was hardly anything there to remember them. All their wood had drifted. Waves of galvanised pailing rusted into loss. Only foundations remained. Rows of concrete steps going nowhere fast. Portals of memory drowned in the sea. Some of the yards were haunted with statues and birdbaths. A mold of some nameless little white boy with a basin on his head. The same child cast in concrete and painted enamel-white to live in every single yard on the island. She could see his pristine whiteness didn’t last. He was encased in the blades of sea fans and an ooze of pink coral. Sea stars nested in his basin. Not a bird in sight. Just shoals of fish floating around, indifferent to this child’s drowning. The question haunted her again. She knew how much love she had for the island. Only her people could rival her in that. But she never wanted to be stuck there or anywhere. She could never reconcile that there were those who didn’t want or need to leave. Those that didn’t need to swim. Where would they need to go if the land had everything they needed? That little rock could be enough for them. And this thought stirred her like a hurricane. She clenched her fist and teeth. All she wanted was to hold her little rock in her hands and know it was enough. She tightened around the memory and could feel it warming in her fist. But that rock and her people stared back at her ugly, ugly, ugly. There was no love grown for girls like her. A cold reminder that bloodied her hands with urchin thorns. She knew it would never be enough. Every day before Dorian, she had stepped off-island and into the water. She needed to float in everything that wasn’t landlocked or left for dead. Every horizon was a possibility. Every black depth, a promise that stranded was not the only way to live.

And when Dorian came, the water stepped into her. They had broadcast the disappearance to the rest of the region. A whole island gone. No sign of survivors, which was true. Nobody made it out the same. They say the sea has no backdoor. But for girls like her, the sea was their backdoor. Girls growing soft with gills, pores, and polyps, just as they had grown otherwise. That little pill — that little piece of care — was one of the keys to their survival. Breath had been found underwater. As above, so below. Changing in the ways they needed to. And the sea — so choked with plastic — she changed too. Toxic microbeads. Hormonal plankton. Water in transition. Everything it held, changed. She knew what it was like to suffocate, both her and the sea. And so, she breathed what she could once the air began to thin. Oxygen depleted, estrogen on tap. A different kind of breath for a different kind of life for a different kind of girl. They were one inside each other, she and her — the sea and her. She and all the girls who made it through. A plural her of infinite pleasure. Everything wet was her. She oozed back into memory.

“Is funny,” Keona’s eyes landed on the horizon.

“What?”

“Girls like we,” they paused, lightly grazing the coral blooms budding on their brow, “always had to live ’pon the edges. Alone.” They pointed out toward the horizon, showing her the way to where the island was missing.

The sea was quiet. It was wearing the embers of an evening’s dying sun. Each mumbling wave collapsed on itself before it could rise, retreating back to the hem of its mother’s skirt as if frightened of growing up. She could hear the pitter-patter of sandpipers zigzagging along the shoreline, their tiny feet leaving the lightest trail of fork prints. The twilight cooing of wood doves calmed everything in sight. It always sounded like a mourning song. Maybe they lost something too, she thought. The breeze was sighing all over, caught in the hands of almond branches and the netting thick of manchineel. Everything looked softer than it was. Pink and fuzzy. Even the wreckage looked more like an innocence of driftwood and less like death on its way out. Yes, the sea was quiet for the first time in months. It needed no words and no apology. Now, all this world wanted was to rest. She and the other survivors had been living in the shores and shallows of La Soufrière ever since the sea unbuttoned itself. Made up of lost coral girls and Vincentians evacuated from the lowlands, after so much death had risen from the water, people didn’t much care what you looked like, who you loved, or what bloomed on your body or between your legs. It was a village cathected in hardship and grief, and the most family she had ever known.

“Girls like we,” they paused, lightly grazing the coral blooms budding on their brow, “always had to live ’pon the edges. Alone.”

She was helping Keona nurture a fire. Everything they needed came floating on the water in salvageable debris. Crisis and redistribution — a hurricane promises both. A cast-iron pot burned black in the fire, its mouth gargling hot saltwater with a plump clay bowl islanding its center. The pot lid, upside down, would catch all the vapor and drop it in the bowl. Freshwater for those in the encampment who needed it, for those who couldn’t drink straight from the sea. Looking up from the fire, she rested her eyes on Keona. A bit older, their short, dark, woollen hair was blowing tiny smoke rings from each pore of their scalp. Their skin was a night sky on fire from all the heat that beaded their face with sweat. They were wearing an oversized turquoise button-up as a dress. Dirtied from life, it tried to swallow their body but couldn’t stomach their thighs. Thick with a happiness of fat over muscle, they glowed greasy from the flames they were determined to keep alive.

“Look,” they blinked away some sweat. She was always a little nervous whenever Keona began to speak. Their words sometimes had the power to encircle her like waves.

“All the edges closer now. Is only edges left back,” she held her breath, letting their voice wash over her. Beneath her feet, the island receded. She tried to anchor herself, knowing Keona would never try to hurt her. Their words were difficult but she knew they would always be a gift. She weighted herself in it, dropping to the seafloor of Keona’s offering. The edges grew closer and she let herself feel what that could mean. She could hear the village buzzing around her. People working to keep themselves alive. Doing this by keeping each other alive. A mixture of voices, once bodied with threatening differences. The luxury of fear scraped out like a coconut’s heart. Dorian had come and pushed them all together. To here, of all places. A barely-there village bowing meekly at the skirt of a volcano. Sardined by disaster, their worlds grew small and overlapped. There was nowhere to hide here. No need to hide.

Her breath returned, steady and grounded. Keona had felt her rolling their words around the mortar of her mind. They looked over her slowly, taking in this girl — this newfound sister — and all they shared together. They scanned the coral budding down the lengths of her arms. Each flower was ripe and supple. Hundreds of tiny amber lips pouring out of her. What were they becoming, she and Keona? Not quite coral, not quite human. But between wasn’t where they were, either. Keona gave her a look of affirmation, letting their gaze hold the coral on her sister’s body. She could feel what Keona was seeing, the blurry vision of herself becoming just a little clearer. She could feel herself feeling seen as an entirely new experience, one that could outswim any known horizon.

“You think they hear ’bout we?”

“Who?” Her brow furrowed.

“You know, them girls ’pon the other islands,” Keona’s words slipped their way in like high tide. Her mouth hung open trying to catch an answer. She was only just getting settled on this island. She hadn’t had the space to think about other islands, let alone other girls. Keona’s point had again unmoored her. Theirs was the island chosen to disappear completely in the roulette of seasonal disaster. Nowhere had stayed the same, but the other islands were still there. They had survived effacement. And there were still girls out there. Landlocked girls, stranded, trying to make life on the edges of other islands. Had anybody told them what had happened, what had changed?

“And what if they did?” she challenged Keona to soothe her.

“Well, think if it was you. What you would do?”

Keona wasn’t easy at all. They let the challenge slip back into her hands like a glob of jellyfish. But she knew all too clearly what she would have done. If she knew she couldn’t drown, she would have stepped straight into the water and never looked back. Safety at the surface was never something she could rely on. The safest space she had known was in the belly of the sea. But it was a safety bought with loneliness. Swimming out into the deep, she knew that no one could endanger her because she was the only one there. It could never be enough for her, of course, but now maybe it didn’t have to be. The water’s surface trembled in her mind, giddily breaking with all the possibilities. She could see them on the horizon, a sea of girls like her. Bodies both like and unlike hers, and the ocean was big enough to hold all of them. Lungs filling with seawater, new-growth corals breathing in their place, they could drop their shoulders, loosen their swinging hips and let all that salt air untether them from harm. She loved that for those girls. She wanted all of it for them. And for her too. She let her vision pool in her hands. Turning their backs on the surface, they would find it. A whole new world to breathe in.

The seaweed was beginning to thin above her and the water grew shallower and shallower. She could feel the sun burning through like holes gnawed out of a rusty tin roof. Its stinging woke her up. Her body knew it was almost time. She would soon become a colony. Beneath her, the road disintegrated into sand and mud. It was much saltier up here. It all looked so murky, except for the black wet roots that tentacled the ceiling. Everything felt unstable, slippery and dark, like she was crossing a dying mangrove. Maneuvering the brambling roots, she noted all the grief as she climbed toward the surface. Fruit trees bowed low, stripped of their bounty. Palms and pawpaw stalks swayed headless in the wheezing current. The ground beneath her, a skull of limestone razed of any and all memory. Like no blood had ever spilled here. Like no cane ever grew. Sunken out of place, everything lay damned. And with each step, the water turned hotter and greener. It was hard to move in this much heat. She could barely think. The mud was biting her heels and all her polyps screamed into the sun. Since she, the coral, and the water were bonded by the breath, she worried the surface was still no place for girls like her. It glittered right atop her head, trembling from its own ripples. She stared upward, frozen, as if the ceiling was going to collapse. As if the sky would drop a house on her for who and what she was becoming. For who she’d always been. A girl who swam too far out, now turning to come home. Light danced on her face and the gentlest pain fluttered across her, tingling any new corals that had begun to flower.

The shape of the island was pooling through the surface. Reading the ripples, there wasn’t much to look at. It was scalped of anything she would have recognized. She could only make out some blackened spindly trees eeling into the sky. It did look like a sea urchin, she thought. Small, fragile, and protective of itself. Just trying its best to survive in a turbulent world. Beautiful to see and dangerous to touch. She wondered whether the island would let her hold it this time. Right beneath the surface, she continued to hesitate. She didn’t know how to move and that wasn’t because of the coral. The decision to resurface was pinning her in place. Nothing here was recognizably her island. She didn’t know what she was returning to. Everything was new. It had just resurfaced. And she wasn’t sure if she even had the right to demand so much from this place. She didn’t even know if the island could remember her. She just kept looking, not sure what to make of it. This fragile little place flickering through the unsteady window to the surface. She watched as it trembled in the play of light and water. Over and over, it was dissolving, falling apart and coming back together, like it couldn’t decide what it wanted to be. The island just kept changing.

Ada M. Patterson (they/she) is an artist and writer based in Barbados and Rotterdam. Working with masquerade, video, and poetry, she tells stories and imagines elegies for ungrievable bodies and moments. Their writing has appeared in Sugarcane Magazine, PREE, Mister Motley, and Metropolis M.

Carolina Rodriguez Fuenmayor is an illustrator from Bogotá, Colombia.