It’s a tough world out there for a line chart. But, with big screen appearances in An Inconvenient Truth and PowerPoint presentations in classrooms across America, the Keeling Curve has earned its place as one of climate change’s most iconic stars.

Wikipedia CommonsUp and up and up and — shit.

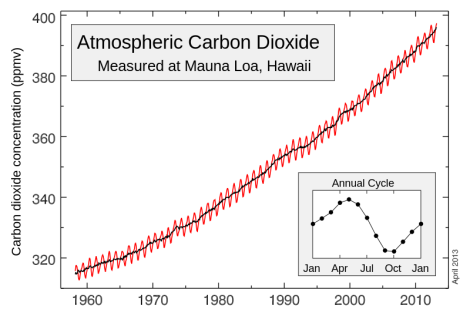

In 1958, Charles David Keeling started collecting data on how much carbon dioxide was in the atmosphere, taking measurements at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. After he died in 2005, the project — part of the Scripps CO2 Program — was taken over by his son, Ralph Keeling. They’ve recorded relentlessly upward trajectories of atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

Ralph Keeling, keeper of the Keeling Curve.

Keeling’s very first measurement was 313 parts per million (ppm) — already up from the pre-industrial levels of about 280 ppm. Last year, we briefly crossed the 400 ppm threshold for the first time, and now measurements that high are only becoming more common. While climate groups like 350.org have chosen 350 ppm as the level for which we should strive to keep shit from really hitting the fan, scientists are already seeing that as unattainable. “I would say at this point that even stopping it from rising beyond 450 is looking almost impossible,” Keeling Jr. tells Grist. Getting back down to 350 ppm “will require not just reducing emissions but also active removal of CO2 from the air.” In other words, cover your heads, things are going to get messy.

But now the Keeling Curve, the longest-running record of atmospheric carbon dioxide may be coming to an end, thanks to budgetary distress.

Keeling Sr. struggled to maintain funding to keep his curve even back in the mid-1960s, but now financial troubles are reaching their most dire point yet, says Keeling Jr. His lab group, based at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, has been trying to branch out from traditional sources of green, like the National Science Foundation, to modern approaches, like asking for donations via Twitter and their blog. These crowdfunding efforts have raised more than $17,000 so far — just a small portion of the program’s $1 million annual budget, but still a strong sign of public support — and they’re still accepting donations.

“The level of funding for science in this country has not grown sufficiently to keep up with the demand and need,” Keeling says.

While the Keeling Curve was the first to provide a long enough time series of atmospheric CO2 to correlate its rise with the burning of fossil fuels, it’s no longer the only group to track such trends. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration now also gathers air samples from around the world to monitor greenhouse gas levels. So is the Keeling Curve still needed? Keeling argues that it is. “If you’re measuring something over time, as we are, you only get one chance to get it right,” Keeling says. “And the only way to be sure that you got it right is to do it more than one way … It’s really integral to having a good record to have some redundancy.”

Plus, Keeling says that his curve is still providing data that enables scientists to make new discoveries. In the last year, Heather Graven, a former post-doc in his group, used the data to publish a paper on how the annual swings in atmospheric CO2 are becoming more intense. “It catches us by surprise that the planet is changing that fast by that much,” Keeling says.

And the Keeling Curve has played a big role in convincing scientists and non-scientists alike that this whole climate-change thing is a pretty dire deal. Unfortunately, it’s only getting more so.