Looking for ecological lessons in The Hunger Games? Give it up, says Paolo Bacigalupi.

“A very influential critic once said, ‘Don’t argue with the book,’” Bacigalupi says. “Hunger Games is not a book about how the world came to be this way. It’s a thought experiment about a theoretical world. Trying to turn it into a parable of eco-collapse is forcing it in a direction that it was not meant to go.”

Bacigalupi should know. He’s a guy who writes eco-parables for a living. His first novel, The Windup Girl, is set in a world shaped by climate change and bioengineering. His most recent book, a young adult novel called Ship Breaker, takes place in an energy-starved future where kids scavenge for precious metals amid the ruins of old oil tankers. The books have won every award known to science fiction. Ship Breaker was a finalist for a National Book Award.

Of The Hunger Games, Bacigalupi says that author Suzanne Collins just needed a way to clear the slate. “In the ’70s, Collins probably would have said it was a nuclear war,” he says. “It speaks to the broader zeitgeist that global warming has become the new bogeyman, but that’s as far as you can take it. She wanted to tell a story about kids killing kids, and media.”

What does a real ecological parable look like? I caught up with Bacigalupi recently to explore this question, and to talk about his latest work in science fiction, or futurism — or whatever it is that he does. (In addition to being a science fiction star, he’s also an old friend of mine.)

Q. You used to prefer the title of “futurist” over “science fiction writer,” but it seems like everybody is a futurist these days.

A. It’s such a snazzy title. Everyone wants to put “futurist” on their business card. The problem is that, you tell someone that you’re a science fiction writer and people say, “Oh, I don’t read that.” I think of myself more as an extrapolationist.

Q. Sounds like a circus act.

A. I look at some trend, or at some event that’s happening in the present and then I ask, “Well, if this goes on, what will the world look like?” If genetically modified foods are the only foods available, and they’re patented by Monsanto-like corporations, and there’s a terminator gene, how does that spin out? If oil really does become a scarce commodity and we fail to bridge to other energy sources, what’s that look like?

Most recently, it’s been this question of, what if we can’t even function as a society where we can solve big problems? What if we hit a moment where our gridlock and our politicized dialog and our willingness to vilify each other means that we cannot address reality any more — that we cannot even engage with the idea of global warming?

Q. What were the real-world questions and seeds that inspired your last book, Ship Breaker?

Q. What were the real-world questions and seeds that inspired your last book, Ship Breaker?

A. With Ship Breaker, I knew I wanted to write about the end of oil, the collapse of our global economy, and about the implications for the rich and poor. I had come across this documentary about a photographer named Edward Burtynsky called Manufactured Landscapes. There were these astonishing images of the ship breaking work in Chittagong, Bangladesh. I’d known that this was going on, but Burtynsky’s photos were so haunting that they buried into my head like a little worm.

When I started working on Ship Breaker — which had nothing to do with ship breaking at the time — those images were still in my head. And they became a frame for me. Our global economy is based on moving big freighters and tankers all over he world. [In the book,] these tankers are the bones of the old world. Then I wanted to mirror that with something that represented some kind of sustainable economy.

Q. The newfangled clipper ships that the ship breaker kids are always lusting after.

A. I’ve always wanted to make sustainable energy sexy and fast and cool, because a wind turbine is just not appealing. When you read the popular science magazines, or you look at Hot Rod and Robb Report, technology is so eroticized. If you look at a really, really fast car, it’s hard not to pop a boner over it. You’re supposed to salivate over your iPad.

So I created these high-tech, very fast, hydrofoil sailing ships. I started thinking, if we’re still clever monkeys, just because we run out of energy doesn’t mean that we become ignorant. If we were to throw our engineering know-how into wind power again, if we said, “We’re going to have a new Wind Age,” how sleek and fast and amazing would a sailing ship be?

Q. I think the balance of those two worlds — the apocalyptic, post-oil world and the bright, Wind Age world — is part of the appeal of the book.

A. There is a lot of criticism about science fiction and future fiction being very dour right now. People talk about the popularity of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, or The Walking Dead on TV. In a way, I think that’s an honest reflection of the implications of us being short-sighted and selfish about our own well-being in the near term, and neglecting our children’s future.

At the same time, science fiction has been an inspirational literature for technology for a long time. You have the classic examples of NASA scientists who became excited about working on rockets because they read about rockets in their books. You have software developers who read Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash and said, “We want to build a world like his metaverse,” and now you have Second Life, an honest-to-God virtual reality game — if you can even call it a game.

You don’t want to write consolatory literature. You don’t want to say, “Technology is going to save us.” It isn’t right now. But you do want to put some signposts out there: Wouldn’t it be interesting if we thought about global trade this way instead? You have this idea that if you get a kid at the right age reading about this, or an engineer reading about this, they might say, “I bet I can make something like that.”

Q. Are your readers building next-gen clipper ships yet?

A. There was this really powerful moment for me when this graphic design student in L.A. sat down and started laying out designs for a hydrofoil clipper ship. You could see that germ lying out there: First you think of it, then you see it, then someone is going to go out there and build it. That was hugely satisfying.

Q. Ecological catastrophe plays into other science fiction books — I’m thinking of Delirium and Birthmarked — but I can’t think of a lot of other authors who build eco-parables into their work as integrally as you do.

A. The environmental community is starved for decent fiction parables for the fears that we have, but it still feels like I have a lot of territory to myself when I’m writing about these topics. It’s interesting to me that there isn’t a whole spate of global warming books. A friend of mine, Tobias Bucknell, just came out with a book called Arctic Rising. It’s a what-if book about what happens after the ice cap melts. But we had been talking about general global warming topics for ages before then. You keep looking over your shoulder, going, “Where is the next book like this?”

When I wrote Windup Girl, everybody told me that science fiction didn’t sell. Then the book actually did sell. Everyone was standing around scratching their heads. I have to think that it sold because it is poking at questions that are relevant right now and have a lot of uncertainties around them. It was all about bioengineering and GMO foods and agricultural control of foods and monocultures.

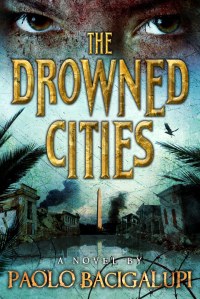

Q. Your next book, Drowned Cities, hits bookstores May 1. What can we expect?

Q. Your next book, Drowned Cities, hits bookstores May 1. What can we expect?

A. Drowned Cities originally was going to be a direct sequel to Ship Breaker. I wrote that book. It was genuinely terrible. I started over from scratch.

I had been thinking about Fox News and our political conflicts and our inability to be realistic about the world. You see that in the weird Republican primary where everyone takes an oath that says they don’t believe in global warming. At the time [I was writing], we were seeing the protests in Wisconsin over the union busting the governor had done. I said, “Wow, this is where democracy fails. You can’t make a decision. You deliberately alienate and crush those people you don’t agree with.”

The drowned cities are a place of perpetual war. It’s based in Washington, D.C., and its suburbs. It’s the last snapping remnants of this political fight that just devolved and devolved to the point where the only people who are fighting are these child soldiers, for factions that nobody even knows why they exist. That’s the heart of the story — about a world that we broke, and these kids that are trying to find some way to thread through the rubble and the bullets.

Q. Is there a beautiful clipper ship sailing offshore — or the equivalent?

A. Is there a positive note? Some of the kids survive. To be honest, this seems a lot closer to my adult work. It gives significantly less comfort. The message is, “Welcome to the world that we’re handing to you, kids. I hope you get through it.”

That’s probably the biggest metaphor for all of our environmental question marks: Our business-as-usual is a big gun, cocked and loaded and aimed at the faces of our young people. The adults are getting off scot-free, while the kids eat all the consequences.