There’s a new scientific paper out in the journal Nature called “Approaching a state shift in Earth’s biosphere.” In a sane world, it would be front page news. This is from the abstract:

Localized ecological systems are known to shift abruptly and irreversibly from one state to another when they are forced across critical thresholds. Here we review evidence that the global ecosystem as a whole can react in the same way and is approaching a planetary-scale critical transition as a result of human influence. [my emphasis]

As examples of past global state shifts, the authors cite the Cambrian explosion (“a conversion of the global ecosystem from one based almost solely on microbes to one based on complex, multicellular life,” which took a comparatively brief 30 million years), the Big Five mass extinctions, and the last glacial-interglacial transition, which started about 14 thousand years ago.

The difference today is that human beings are generating “forcings” (influences on biophysical systems) of unprecedented power at an unprecedented rate. These forcings include “human population growth with attendant resource consumption, habitat transformation and fragmentation, energy production and consumption, and climate change.” The authors emphasize that all these forcings “far exceed, in both rate and magnitude, the forcings evident at the most recent global-scale state shift, the last glacial-interglacial transition.”

This write-up from Wired adds some context:

Human activity now dominates 43 percent of Earth’s land surface and affects twice that area. One-third of all available fresh water is diverted to human use. A full 20 percent of Earth’s net terrestrial primary production, the sheer volume of life produced on land every year, is harvested for human purposes. Extinction rates compare to those recorded during the demise of dinosaurs and average temperatures will likely be higher in 2070 than at any point in human evolution.

Humanity’s footprint now covers Earth. We are shaping the biosphere in our image.

So, what would such a global state shift entail? There’s no way to know for sure, given the number of systems interacting in unpredictable ways, but we can learn from history:

On the timescale most relevant to biological forecasting today, biotic effects observed in the shift from the last glacial to the present interglacial included many extinctions; drastic changes in species distributions, abundances and diversity; and the emergence of novel communities. New patterns of gene flow triggered new evolutionary trajectories, but the time since then has not been long enough for evolution to compensate for extinctions.

At a minimum, these kinds of effects would be expected from a global-scale state shift forced by present drivers, not only in human-dominated regions but also in remote regions not now heavily occupied by humans; indeed, such changes are already under way.

Given that it takes hundreds of thousands to millions of years for evolution to build diversity back up to pre-crash levels after major extinction episodes, increased rates of extinction are of particular concern, especially because global and regional diversity today is generally lower than it was 20,000 years ago as a result of the last planetary state shift. … Possible too are substantial losses of ecosystem services required to sustain the human population. … Although the ultimate effects of changing biodiversity and species compositions are still unknown, if critical thresholds of diminishing returns in ecosystem services were reached over large areas and at the same time global demands increased … widespread social unrest, economic instability and loss of human life could result.

Whee!

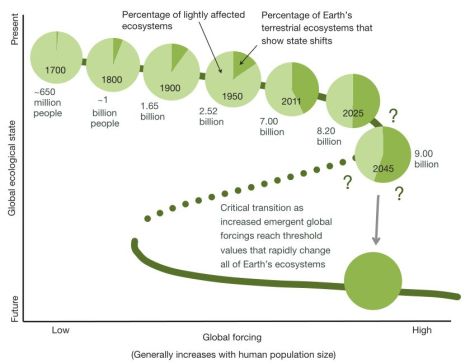

How close are we to such a global state shift? One way to conceptualize it is to visualize the percentage of the Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems that have seen local state shifts:

The $6 kajillion question is: what percentage of local systems have to see state shifts before a tipping point is reached and the Earth as a whole enters a state shift? It’s impossible to say for sure, say the authors, but “landscape-scale studies and theory suggest that the critical threshold may lie between 50 and 90% (although it could be even lower owing to synergies between emergent global forcings).”

We’re on track to hit 50 percent in about 10-15 years. Then we enter the danger zone, facing an uncertain but looming shift into global conditions never witnessed by human civilization. (This reinforces the conclusions of a seminal 2009 study in Nature on our proximity to “planetary boundaries.”)

This is from the study’s conclusion:

Humans have already changed the biosphere substantially, so much so that some argue for recognizing the time in which we live as a new geologic epoch, the Anthropocene. Comparison of the present extent of planetary change with that characterizing past global-scale state shifts, and the enormous global forcings we continue to exert, suggests that another global-scale state shift is highly plausible within decades to centuries, if it has not already been initiated. As a result, the biological resources we take for granted at present may be subject to rapid and unpredictable transformations within a few human generations.

We have no precedent for that. We have no idea if we could survive it, much less thrive in it, and even if we could prosper through it, whether we want to wipe out most of the other species on Earth. Here’s what the authors recommend:

Anticipating biological surprises on global as well as local scales, therefore, has become especially crucial to guiding the future of the global ecosystem and human societies. Guidance will require not only scientific work that foretells, and ideally helps to avoid, negative effects of critical transitions, but also society’s willingness to incorporate expectations of biological instability into strategies for maintaining human well-being.

That dry phrase, “incorporate expectations of biological instability into strategies for maintaining human well-being,” implies a transformation in how humans think, plan, and behave that is hard to get your head around. Humans have been living as if biophysical resources are infinite for so long that we have only the faintest clue what it might look like to do otherwise.

The time in which we can safely make such a transition, however, is running out. These are not normal times.

——

Here’s a video of lead scientist Anthony Barnosky summarizing the findings: