The conflict between electric utilities and distributed energy — mainly rooftop solar panels — is heating up. It’s heating up so much that people are writing about electric utility regulation, the most tedious, inscrutable subject this side of corporate tax law. The popular scrutiny is long overdue. So buckle up. We’re getting into it.

I wrote about the fight a while back — “solar panels could destroy U.S. utilities, according to U.S. utilities ” — but it’s worth taking a closer look at what’s under dispute. Some bits are unavoidably wonky and technical, but it’s important to understand exactly what’s happening. This is a pivotal issue, a trial run for many such struggles to come.

There’s a short-term problem and a long-term problem. The former is about how electricity rates are structured, specifically how utilities compensate (or don’t) customers who generate power with rooftop solar PV panels. The latter is about developing an entirely new business model for utilities, one that aligns their financial interests with the spread of distributed energy. The danger is that fighting over the former could delay solving the latter.

Today, let’s dig into the fight at hand. It’s about utility rates, specifically “net metering,” yet another nerdy green term no one understands. I will endeavor to make clear what it is and why the fight over it is so damn interesting and exciting. Exciting, I tell you! Wake up!

The utility perspective

First, note that I’m focusing here mostly on investor-owned utilities (IOUs), which serve about 70 percent of America’s customers. These are the old-school, for-profit, regulated-monopoly utilities, with a captive customer base and profits guaranteed by law. IOUs are the main (though not exclusive) force pushing back against distributed solar.

Here’s how IOUs make money: 1) they estimate how much power their customers will need; 2) they estimate the investments they’ll need to make in power plants, fuel, transmission lines, etc. in order to meet that demand; 3) they estimate what rate they need to charge customers to cover those investments and offer a reasonable “rate of return” to their investors; 4) they go to the state public utility commission (PUC) to make a “rate case” justifying the rate; 5) if the PUC signs off, the IOU charges that rate until time to make their next rate case.

The free market in action! [cough]

Anyway, that’s the rate residential customers pay: the PUC-approved “retail rate.” Typically, the retail rate bundles all the utility’s costs into a single package, not just the “variable costs” of fuel and electricity but also the “fixed costs” of investment in transmission lines, transformers, power plants, and the like.

That’s all background. Now. Into this milieu comes “net metering,” a policy in place in just over 40 states (though the details differ substantially from state to state). Under net metering, a residential customer with solar on her roof is credited the retail rate for the electricity she produces. If she produces as much electricity as she consumes, her bill nets out to zero. That means she’s not paying for electricity, but it also means she’s not paying anything toward the utility’s fixed costs. As more customers zero out their bill through net metering, fixed costs will be transferred to a smaller group of ratepayers, thus raising their rates (and their unholy ire).

According to utilities, this is not fair, since solar customers are still making use of the grid and the services that utilities provide. In fact, they say, the complexity of managing thousands of distributed solar panels makes grid management more difficult and costly. Through net metering, the customers who can’t afford solar end up subsidizing grid services for those who can.

That’s why utilities view net metering as unsustainable. That’s why they’re going after it in California, Texas, and elsewhere.

The immediate solutions favored by utilities are well-captured in the first two recommendations from that now-infamous Edison Electric Institute paper (the one where the utility trade group predicted a solar-induced death spiral). The first is that utilities institute a “monthly customer service charge to all tariffs in all states in order to recover fixed costs.” This “fixed charge” is something all homeowners would have to pay, whether or not they’d created a net surplus of electricity.

The second is to “develop a tariff structure to reflect the cost of service and value provided to [distributed energy] customers,” said service and value consisting in “off-peak service, back-up interruptible service, and the pathway to sell [distributed] resources to the utility or other energy supply providers.” To my ears, this sounds like a recommendation to pay rooftop solar producers wholesale rather than retail rates.

David Rubin of Pacific Gas & Electric sums up:

We need to set the stage for continued growth in solar in what we believe will be a sustainable way which is to not have solar customers that are being subsidised by the rest of our customers and producing unsustainable rates for those customers.

The solar perspective

Solar installers, customers, and advocates are not impressed by these arguments. In fact they are up in arms. Some of the country’s biggest solar installers have formed a group call the Alliance for Solar Choice to defend net metering. (This is happening in Australia too, where a campaign called Solar Citizens was just started for the same reason.)

They say: Gimme a break. Utilities don’t care when rates rise. That’s how utilities make their money.

Imagine if Walmart had a monopoly on retail sales. It could charge whatever it wanted for its goods, as long as the charges were approved by a PRC (public retail commission). In fact, the more Walmart bought, the more warehouses and stores it built, the bigger its truck fleet, the more it could justify charging customers. It was guaranteed a healthy rate of return on its investments, whether or not those investments were wise, whether or not customers end up needing them.

Would monopoly Walmart have any reason to object to rising retail prices? Of course not. Would it have any incentive to reduce costs? Of course not. As long as it’s got a captive customer base, it has no incentive to innovate or take chances.

That’s why utility customers are getting shafted all over the country. Utilities overestimate demand, underestimate efficiency, and contract for gigantic central-generation power plants that customers pay for whether or not they need the power. Why just elsewhere in California, Southern California Edison customers have been paying on the order of $68 million a month for a “refurbished” San Onofre nuclear plant that crapped out over a year ago and hasn’t produced a watt since. In Mississippi, rates are rising to pay for the new Kemper County coal-fired power plant. We Energies in Wisconsin is trying its damnedest to raise rates on its customers to pay for the ill-fated Oak Creek coal plant. And so on.

So no, utilities are not upset that solar is (allegedly) increasing some customers’ rates; they’re upset that solar is reducing their revenue. Rooftop solar panels are investments upon which utility shareholders receive no return. It’s competition they don’t like, the potential loss of their captive customers.

That, say solar advocates, is the core utility incentive, so anything from utilities about what they “need” to cope with solar should be taken with a large teaspoon of salt.

Relatedly, the notion that onsite solar generation and consumption is a “cost” to utilities is somewhat Kafka-esque. A home creating its own power basically unplugs itself from the grid. If you unplugged an old freezer or TV, would that be a “cost” to the utility? After all, the electricity that’s generated onsite on a solar home is used by that home or its immediate neighbors. It barely touches the utility’s transmission and distribution system. It is effectively delivered energy, which is why it gets the retail rate: It saves the utility on transmission and distribution costs. It also reduces line losses and the cost of meeting state renewable energy targets.

Nonetheless, last year, California Assemblyman Steven Bradford (D) — chair of the Committee on Utilities and Commerce and, ahem, a former Southern California Edison executive — managed to pass AB2514, which mandated that California PUCs consider onsite solar a cost. That’s how California utilities are trying to justify new fixed charges.

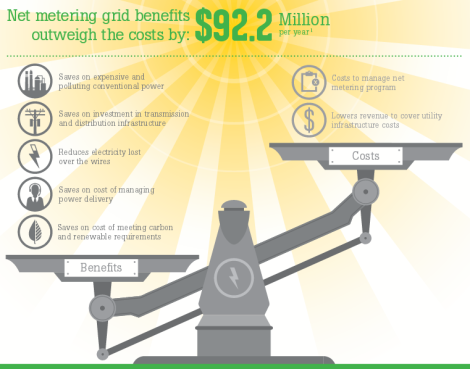

Tom Beach of energy research firm Crossborder Energy took those benefits into account when he analyzed the costs and benefits of net metering in California and (in a separate study) Arizona. He found that net metering will create a small net benefit for all customers: $92 million a year for customers in California and $34 million a year in Arizona, both by 2015. (Both these numbers are small beans relative to total utility revenue, by the way.)

This is from a Vote Solar infographic [PDF] on the California study:

Vote SolarClick to embiggen.

And finally, solar advocates argue that utilities are ignoring the load-reducing benefits of distributed energy (and energy efficiency) in their resource and infrastructure planning. Distributed energy and efficiency reduce the utilities’ fixed costs by reducing the need for new power plants and transmission lines, but utilities don’t take that into account. They end up planning for — and justifying rates for — a level of infrastructure they won’t actually need. So those rising rates they’re squawking about are in part due to their own poor planning. Nick Chaset, energy advisor to California Gov. Jerry Brown (D), put it this way earlier this year:

… there is a bit of a disconnect in utility planning. … Typically, the investor-owned utilities do not fully account for the expected deployments of distributed resources in their distribution infrastructure planning. … [As a result,] we do some degree of double-paying. We are paying for the rooftop solar and a distribution system that is accounting for expected load growth that might be offset by that rooftop solar.

If utilities would plan around distributed resources better, solar advocates say, maybe they wouldn’t need to raise rates so much.

It’s not simple

My sense, looking on this battle from the outside, is that solar advocates have the stronger case, but that they’ve been a little too quick to go to Defcon 1 and tar all utilities as evil. Some utilities, at least, seem to be grappling with this issue in good faith.

Here’s a kind of parable. CPS Energy in San Antonio, a municipal (not investor-owned) utility generally considered a friend of solar, last month announced that it would scrap its net metering program and replace it with a “solar credit” worth about half as much. Solar advocates went ballistic. Among other things, they compared CPS unfavorably to Austin Energy, which offered a solar credit that was roughly twice as large.

Well, since then, CPS Energy has agreed to delay its move for a year, giving it time to work with solar advocates and installers to find a solution acceptable to everyone. Meanwhile, Austin Energy reduced its rebate for new solar installations.

This is not to say either utility is in the right, just that even the “good guy” utilities are struggling with the question of how to appropriately compensate for distributed solar. The fact is, as long as utilities operate under their current business model, rooftop solar really does hurt them.

What’s ultimately needed is not this kludgy, rate-jiggling solution, which will have utilities and solar advocates forever squabbling over pennies on the margins, but a deeper rethinking of the utility model, particular the investor-owned utility model.

It is to that deep thinking we will turn in my next post.