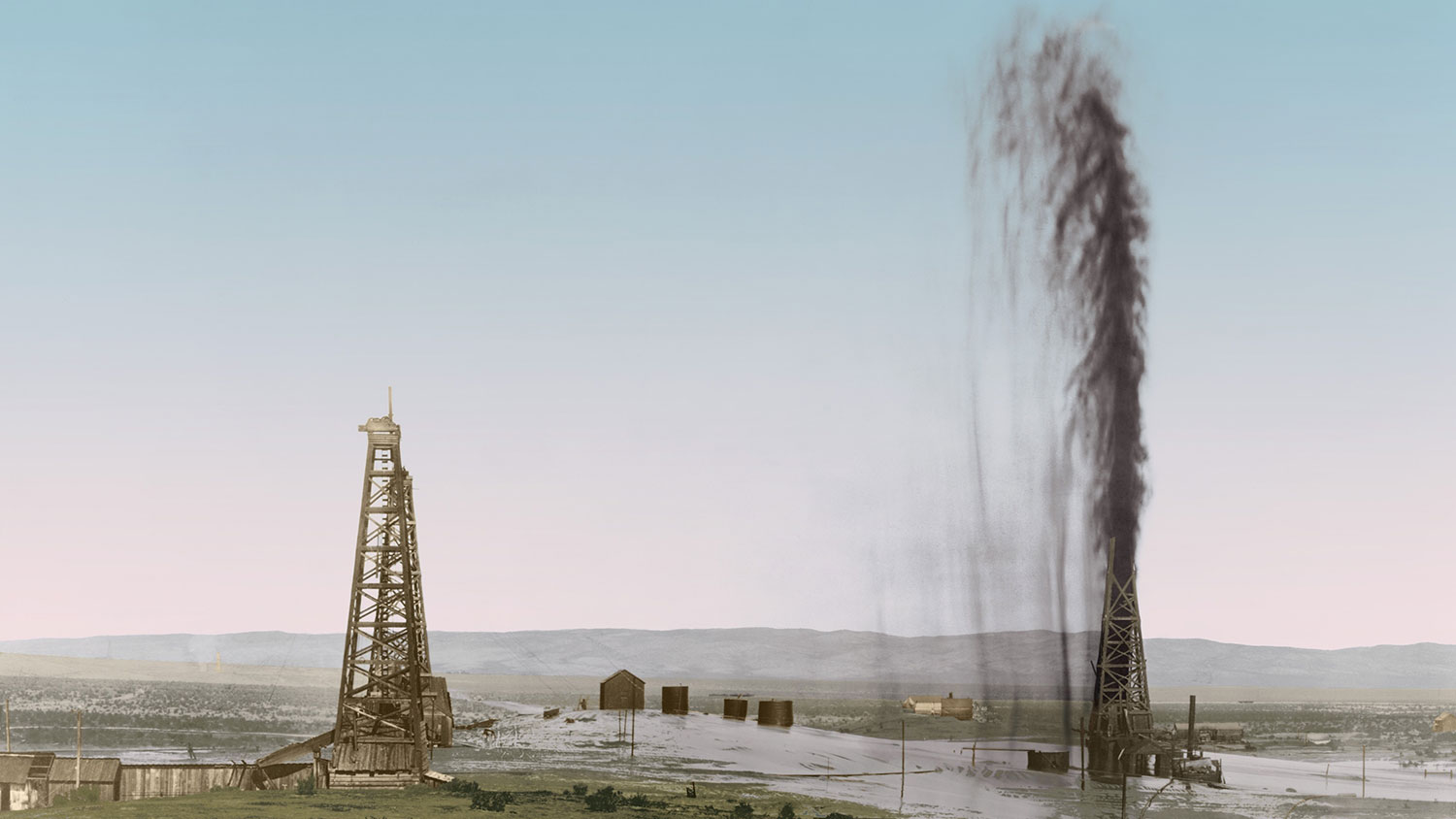

With one quick drop in the price of oil, the shale oil boom is officially bust. In less than a week, 61 oil rigs across the United States closed up shop, according to the most recent rig count from Baker Hughes. The U.S. has 1,750 oil rigs still hunting for new oil wells, but that number is expected to fall by another 400 rigs by the time spring rolls around.

The whole episode is a wake-up call about just how much of a fairy tale North America’s oil boom really was. It was a fairy tale with real drills, sure — and since it was exempt from the Clean Air and Clean Water acts, it will continue to have real consequences for the people living near it. But when it costs Saudi Arabia $10 to get a barrel of oil and it costs shale oil operations around $65 to make that same barrel, it should have been obvious that America was only a titan of oil production because another country was letting us be.

The U.S. got the excitement of overtaking Saudi Arabia and becoming the biggest producer of oil in the world for a few months this summer. Then Saudi Arabia did what it always had the power to do and raised its oil output so that prices fell.

“Those who are producing the most expensive oil — the rationale and the rules of the market say that they should be the first to pull or reduce their production,” Suhail Al Mazrouei, oil minister for the United Arab Emirates, told reporters recently, sounding more than a little like an Econ 101 professor. “If the price is right for them to produce, then fine, let them produce.”

That price — which was $110 per barrel this summer, and $80 three months ago — is now hovering at $46. Goldman Sachs estimates that it will drop to $40 in a few months, since it will take a while for production to slow down and adjust to the new pricing.

Since late November, the United States has cut 10 percent of its oil exploration, and Canada has cut back 25 percent. If this continues, expect the oil boom towns of Alberta, Texas, North Dakota, and Colorado to start looking more like ghost towns.

When are prices likely to rise again? Goldman Sachs estimates they’ll begin rebounding at the end of 2015. Others warn that the situation could be more like the oil price drop of 1986, which lasted about five years.

All of which means that TransCanada may well find itself delighted that protesters stopped it from building a big, expensive pipeline to get now-unprofitable tar-sands oil to market. I wouldn’t count on that one, though.

CORRECTION: This post originally misidentified the nature of the rig count referred to in the first paragraph. It is a measure of the number of rigs looking for oil, rather than the number of wells that are in production — so the drop is in exploration, rather than total production. Grist regrets the error, and has sentenced the writer to hard time served reading the rotary rig count FAQ page.